Two very contrasting approaches to Occupy from British cultural studies have recently been published. One thinks that Occupy still has to reach 98% more people. The other sees it as a new expression of the “general will,” by and against which decision making is measured in democracies. While both measure their distance from OWS, it turns out I am involved in the dispute.

Sunil Manghani, reader in cultural and critical theory at York St John University, takes my blog post “Occupy Theory” as a key point of reference and critique for his op-ed in the Times Higher Education Supplement. We learn first that the students in his course did not recognize the #OWS hashtag or find their field trip to Occupy London very exciting. It’s not clear why this is so important. Manghani opines “it is the ‘theory’ behind Occupy that is the wider preoccupation.” Yes, folks, we’re back in the theory wars, I’m afraid.

Manghani then muses over my post, finding it “conceptual” despite my explicit claim that Occupy is a performative. The clincher for Manghani was watching a video of Judith Butler speaking at OWS, in which she read her remarks from an iPhone. There are a couple of things wrong with this.

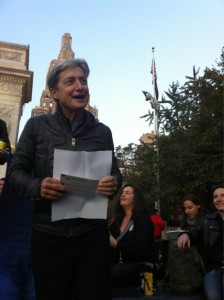

As the picture shows, Butler read her talk from old-fashioned paper: I was standing next to her, I remember it.

Some people did read from iPhones at OWS, though, like Angela Davis. What’s wrong with this? For Manghani, the practice evokes Francis Fukuyama’s thesis of the end of history in the form of liberal democracy, leaving our choices as solely consumer options. Fukuyama himself has backed away from this 1990s position and now critiques such neo-conservative positions. Davis herself spoke of the general strike being organized by Occupy Oakland and a revolutionary turn. She answered questions in the cold for over an hour–without referring to her phone.

For Manghani, the Arab Spring that so exemplifies the end of the end of history is a proper movement, to be visualized, bizarrely, as a Tracey Emin artwork: “gritty yet faltering.” I’m not sure how Tahrir Square evokes the tabloid heroine of British art and her unmade beds? I certainly prefer to be a Rachel Whiteread sculpture, Manghani’s visualization of the “fringe” that is Occupy.

A very contrasting position can be found in a striking piece by Nick Couldry and Natalie Fenton, “Occupy: Rediscovering the General Will,” published on the Social Science Research Council website. Couldry and Fenton, Professors of Media and Communications at Goldsmiths, University of London, see Occupy as a reconceptualization of democracy in the context of both the financialization of everything and the crisis of [Western] democracy. Bringing Foucault to bear on the rise of neo-liberalism, they argue that “markets” are a modern invention (as does London-based Occupy theorist David Graeber), which have become predicated as natural, producing “democracy” as their natural outcome. Yet there is a palpable gap between the promise of democracy’s voice and what it can now offer its citizens: “We have grown used to living in democracies that aren’t working, that is, don’t work as democracies.”

While their argument is centered in the UK, it clearly applies very well to the US, where the Obama election in 2008 seemed at first to reinvigorate the possibilities of representative democracy and has now come to represent the falseness of its operations. Many Occupy activists were inspired by the idea of fundamental change in 2008–and perhaps in 1997 in the UK, with the first Labour victory. What is now, as Couldry and Fenton have it, “so striking about the Occupy movement is that it is a peaceful, collective attempt to face up to that unwelcome ‘post-democratic’ truth and to explore new ways of experiencing the general will.”

The proliferation of Occupy newspapers, journals, blogs, essays, commentaries and other thought-provoking materials is visible evidence of this new general moment, centered, as I suggested yesterday, on exterior discussion. If the general strike is the first moment of refusal, the “no” to markets being everything, the general “yes” is always and already in formation: “Nothing could be harder than this.” Everyone agrees on this at least, including Manghani.

Couldry and Fenton recognize the challenge for those who have the chance to work full-time in universities: “our main task perhaps is to go out from our institutions and listen on the streets, and then, on return, to open our doors.”

The implications of such general, open listening might include:

- free, open, libre publishing

- not publishing Occupy materials with for-profit publishers, especially Rupert Murdoch, owner of the Times newspapers

- learning to listen not “teach”

- not referring to “my/our” students

- maybe not using the word “student” at all?

- working for free, public, universal pre-K to postdoctoral education.

And no, those are not demands.

Thanks for this, Sunil. A couple of quick thoughts: there needs to be a distinction between those who speak as guests at Occupy sites, like Butler and Davis, who are careful not to claim to speak “for” the movement but in support of it; and those who speak as part of Occupy at General Assemblies, working groups and other . These latter interactions are what Couldry and Fenton are describing, which are “desires” certainly but in the Situationist sense: “take your desires for reality.”

Performing is distinct from the conceptual at Occupy because people position their bodies in certain spaces, sometimes at risk to themselves, in the furtherance of a collective undertaking. When a foreclosed house is reoccupied by its former residents, as in the East New York action of December 6, 2011, it may evoke Rachel Whiteread for some: what matters more, surely, is the resheltering of that family?

At least some students in York (at the University of York) agree: they occupied outdoor space recently (December 8, 2011) to counter the “marketisation of higher education.” Good for them!

See: http://www.nouse.co.uk/2011/12/08/york-students-occupy-vanbrugh/

I appreciate the corrections. It is odd, however, the video clip I saw did seem to show an iPhone (and indeed, Nick, a glimpse of you in the background). Nevertheless, I must stress, I was not trying to say it is wrong to use notes, or even to read these off of a phone. My point – if hard to get across in a journalistic piece, which inevitably gets truncated – was about the vast interconnectivity of desires, possessions, needs, consumption etc. etc. I welcome the fact that Fukuyama has distanced himself from his thesis, but I’m not sure it takes away the problem he was originally pointing to. The end of his article reveals existential angst, which I think is conveniently lost in the headlines but remains pertinent. And as for those (ironic) references to Emin and Whiteread – of course it makes no real sense to compare events to these artists. Indeed, I meant for those examples to be jarring – like a pinprick I wanted to prompt further thoughts about differences at stake. Still, if I stick with them one last time, I do sense – like an unmade bed – something more spontaneous and less staged about the Arab Spring. Equally, I’d agree, I prefer Whiteread’s work, but I’m just not sure that’s what is required…

The performative slips over to the conceptual as soon as it has to be explained. I think that is a genuine problem for Occupy – I think that’s what was significant for ‘my’ students and I standing at St Pauls. Oops, Doublespeak! Scrap that line. Replace with: I think that’s what was significant for us standing at St Pauls…

(…and, importantly, as I suggested at the end of my piece, I’m keen to understand how we might tackle this problem for the future(s) of Occupy…)

It was quite intimidating to speak at Zuccotti, even if you’re very used to public speaking. I forgot things I thought I would say because they weren’t in my notes:)

I noticed Zizek read from papers he held in his hand when speaking at Occupy Wall Street. I don’t think there is anything wrong in this. He, like Butler and Davis, probably had a very specific message/statement to relate so they brought notes to avoid leaving out something important.