To the anonymous, as I’ve often said, the police declaim: “move on, there’s nothing to see here.” To form a subject capable of enacting a different history, the anonymous claim at once the right to look and the right to be seen. When I was writing my book, I found it difficult to even imagine this scenario under the pressure of the neo-liberal state of exception. Now it’s possible to think about breaking that process down into a set of steps.

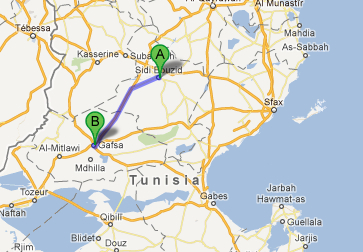

Take the emblematic case of Mohammed Bouazizi, the fruit-seller whose self-immolation on December 17, 2010, set in motion the Tunisian Revolution and from there the global Occupy movement. He lived in a small town called Sidi Bouzid, the epitome of anonymous for many even inside Tunisia. Some 80,000 people live there, and work centers on huge new olive groves planted by the state (M 15) [for references, see below]

About 100 km south-west of Sidi Bouzid is Gafsa, a major phosphate-mining town. In the 1970s, the first cultural dissent against the regime began there, with the formation of an alternative theatre group, including performers like Fadhel Jaziri and Jalila Baccar (M 146). The mining company was given over to members of the ruling clan, specifically relatives of Leila Trabelsi, Ben Ali’s legendarily corrupt wife (G 51). So extreme was the corruption that the entire city rose up on January 5, 2008, protesting unemployment, corruption and repression. Although the occupation lasted for six months, there was a total news blackout. The one journalist who did report it was jailed for four months.

So Mohammed Bouzazi was unlikely to have been as politically naive as he was often presented. Western reports first claimed that he was an unemployed graduate–like many others–but soon retrenched to saying he was a simple fruit-seller. According to Martine Gozlan’s book on the 2011 revolution, the truth was in-between. Mohammed had dropped out of high school to support his family but did want to go to university. One of those he supported, his sister Leila, was in her third year of university ( G 16). For Gozlan, the family epitomized the clash of the “two Tunisias.” There was a high degree of university training with 34% of the population having a degree. On the other hand, the economic crisis since 2008 had led to price rises in basic necessities, mass unemployment and the withdrawal of state ownership in favor of privatization.

However, one year earlier in the city of Monastir, a young man selling doughnuts had also had enough of the police and immolated himself in front of a state building. Nothing happened (M 40). A year later, Mohammed Bouzazi repeated the act, whether in conscious imitation or not, and Tunisia moved to a revolutionary situation. Hamadi Kaloutcha, who blogs as Sofiane Belhaj, is clear that the difference was simple: the diffusion of Facebook and other forms of peer-to-peer communication (M 31, 41). It’s quite unpopular in digital circles here to make this case but Sofiane is not saying that Facebook caused the revolution, only that it allowed for the dissemination of information.

It’s interesting to see that, as the revolution got under way, some of the signature gestures of Occupy were already being used. On January 9, 2011, striking students at Sousse held a general assembly (G 36). In Tunis four days later, key phrases from the national anthem were repeated across the length of the massive demonstration in the manner we now call the people’s mic (G 43).

Back in Gafsa, the workers occupied the phosphate mines again, creating a tent city,

and there were demonstrations, including Che Guevara banners.

By now we should be learning to be careful to make claims of originality. But the emerging story of the Tunisian revolution suggests the following pattern for the emergence of direct democracy:

- economic crisis combined with government and corporate indifference and/or corruption

- a dramatic difference in rhetoric and practice–human rights were taught in all Tunisian schools but not even minimal press freedom existed before 2011

- state violence to repress dissent

- peer-to-peer electronic communications to alert people to what’s happening

- a generalized use of horizontal tools that have been used by a few in specific locations and circumstances

Looking at the list, it’s interesting to see how closely the pattern has been replicated in Western capitalist countries. Let’s hope it does not take more violence for people to want to make a generalized use of direct democracy here.

references:

G: Martine Gozlan, Tunisiee, Algérie, Maroc: La colère des peuples (Paris: L’Archipel, 2011)

M: Abdelwahab Meddeb, Printemps de Tunis: La métamorphose de l’Histoire (Paris: Albin Michel, 2011).