The revolutions in North Africa and the global Occupy movement have seen the emergence of what I call Photography 2.0 in which people and “the people” envisage and visualize themselves as having a name, a place and the right to look. This photography uses phones, graffiti, the Internet, the demonstration and Occupy as its means of self-manifestation. Sometimes it uses cameras as well.

In the moment of the general crash of 1929, Walter Benjamin suggested in his essay on Surrealism

For to organize pessimism means nothing other than to expel moral metaphor from politics and to discover in the space of political action the one hundred percent image space

“Organized pessimism” was Benjamin’s response to a series of failures by the Social Democrats in 1920s Germany. In the so-called Great Recession, it has been Occupy’s response to the failures of the entire political class: because there is nothing to hope for from them, we must organize ourselves. By (re)claiming space, a newly affirmed self-image is placed in the street, in the square, in the place of occupation. It challenges the idea that all there is to do is circulate, to pass by and to continue as if commodity fetishism can still save us.

Organized pessimism: 400,000 “likes” on the “We Are All Khaled Said” page in 2011.

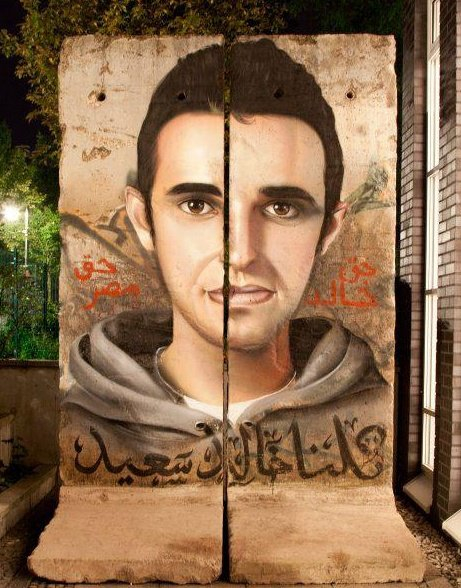

Khaled Said was a blogger, arrested and tortured to death by Egyptian police in 2010. The mural above was painted by Andreas von Chrzanowski aka Case, on a remaining segment of the Berlin Wall in 2011. The texts say: above,”Khaled’s rights are Egypt’s rights” written by Zahraa Kassem and below “We are all Khaled Said”, calligraphy by Mohamed Gaber (photo: Joel Sames/From Here To Fame). It has been proposed by the revolutionaries that Mahmoud Street, which leads from Tahrir to the Interior Ministry, should be renamed for Khaled Said: in their usage it already has been occupied by this revisualized naming.

The image space in the place of political action: “The people want the regime to fall.”

In this famous slogan, now almost a year old, a self-image has formed where there was none before. It organized a collective political subject with desires: not demands. The new general will forced the dictator to yield. In the US, it was the move from posting on “We Are the 99 Percent” to occupying.

In short, there’s a new kind of “photography” taking place. It is a countervisuality to the concept of history in which autocracy, whether the Egyptian dictator or the military-industrial complex, is the only entity capable of visualizing the social and its flows. In Thomas Carlyle’s exaltation of the Great Man or the Hero, the “camera obscura of tradition” that reinforced and supported that visuality. This “photography” aspired to create a Medusa-effect for the modern, immobilizing change and fixing the social hierarchy as it already was. Photography 2.0, by contrast, is an apparatus to name and organize the anonymous.

It is first an extension of the body, whose signature gesture is the young woman photographing herself using her phone at arm’s length. This self-portrait is the counter to the ubiquitous surveillance of the age of Closed Circuit Television (CCTV). It asserts a presence and autonomy, from which can be derived the right to be seen and the right to look. Photography is becoming newly democratic, a literally direct democracy, beyond its first democratization of the means of mechanical visual reproduction in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, to a democracy of the self (image).

In Alexis. A Greek Tragedy, the Antigone character makes considerable use of the Mac PhotoBooth program to take pictures of herself and other characters as the play is taking place. Using the self-timer, she took a picture of herself jumping away from the computer’s camera, which, when rendered in the foreshortened view of the little lens in the MacBook, appeared to show her jumping headlong into the audience. In the same way, Photography 2.0 resolutely breaks the fourth wall and all the distancing apparatus of the Camera Obscura/Lucida. J25 is coming. There is more to follow.