When I first started writing “on violence” after Abu Ghraib, an anthropologist friend warned me that from now on I would find myself characterized by this work. I did not understand what he meant until the very first question on the Abu Ghraib paper was “Why are you showing these to us?” The questioner was in no doubt that, while there were obviously things wrong with the images, there was also something wrong with me for wanting to show them. In the same way that advertising elicits a mimetic response from the viewer (I want that/I want to be like that), it is assumed that critical choice is evidence of preference. So consistent was this response that I later dropped out of a grant project on Abu Ghraib.

Since Chris Hedges’s piece on black bloc, the Internet has been awash with interventions for and against the use of violence that have even reached the comments section of this project. The assumption is the same: if Occupy is violent, and a person likes Occupy, that person must either be violent or “condone” violence. Nowhere is violence defined. A thrown bottle or a broken window count as violence. Calls for context or considerations of police action are ignored.

Just after the failure of the Spartacist revolution in Berlin in 1919, Walter Benjamin wrote a dense essay that sought to define violence in other ways. He quickly set aside the “casuistry” whereby ends and means are permanently debated in favor of the “historico-philosophical” interrogation of the law’s “monopoly of violence.” He saw that the goal of this restriction was not the preservation of “legal ends” but “the preservation of law itself.” Later he would come to call this condition the “state of emergency,” the permanent claim that in order to save the law, it must be suspended.

The clearest example of this distinction for Benjamin was the “class struggle” and the right to strike:

the right to strike constitutes in the view of labor, which is opposed to that of the state, the right to use force in attaining certain ends. The antithesis between the two conceptions emerges in all its bitterness in face of a revolutionary general strike…however paradoxical this may appear at first sight, even conduct involving the exercise of a right can nevertheless, under certain circumstances, be described as violent. More specifically, such conduct, when active, may be called violent if it exercises a right in order to overthrow the legal system that has conferred it

Ironically, German workers in 1919 did have the right to strike lacking for so many in the U.S. today, despite it being enshrined as a fundamental human right in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. In this view, while the general strike was a contradiction within the system, it was not in itself illegal, even if the state perceived it as violent.

However, Benjamin understood the general strike to be different from an ordinary strike “in the determination to resume only a wholly transformed work, no longer enforced by the state, an upheaval that the strike not so much causes as consummates.” In this way, Benjamin saw this vision of revolt as not being violent but rather as “deep, moral, and genuinely revolutionary.” We can in fact go further than he did. Given that late capital has made a great show of the irrelevance of labor to its process, it is clear that the extensive legal prohibition against striking is not due to the “essential” nature of the workforce but rather the need to reinforce its subjection to the force of law.

Of course Benjamin also did describe such strikes as “anarchist” at this time, and he saw himself as a “theological anarchist.” Can we see Benjamin in a bandanna and a hoodie? I tried but my Photoshop skills aren’t up to it.

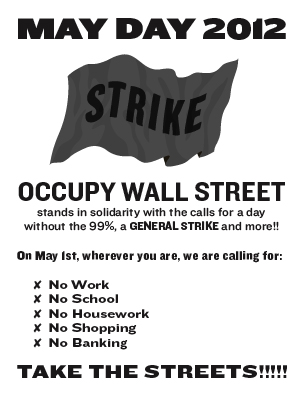

Since January, Occupy nationally has been involved in preparations for a general strike on May 1, May Day. Today, rather than attend a New School conference with excellent speakers like David Graeber and Rebecca Solnit, I spent a long afternoon in a basement working out some details of how this might happen. A substantial group discussed solidarity actions with people organizing in the Bronx over the recent police killings, especially that of teenager Rahmarley Graham. Much time was spent devising a way to interact with the labor unions and other groups that also want to observe May Day in a way that respects their process and that of OWS. Consensus was found. Nobody mentioned the black bloc.

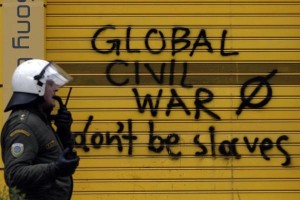

In all the recent criticism, little has been said about the global context. It might be worth noticing that in addition to all the Iran panic, Israel has just had a general strike. Greece has also observed a two day general strike, while even mainstream reporting sees the country on the verge of collapse. On the streets, the view is a little more dramatic:

Yes, they’re talking to you.