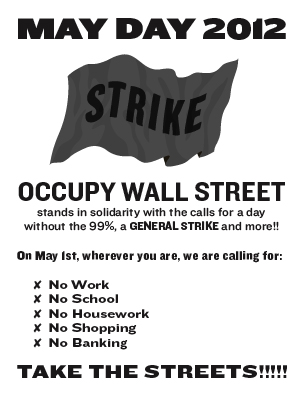

As much as I have wanted to stress the present and future present of Occupy, I keep getting asked to do events or to write about the future of Occupy. I’m coming to think that the “future of Occupy” would be changing the terms of the way that the “economy” is discussed. From this perspective, we can see how two parallel, failing discourses of governance regarding austerity and climate change need to be converged and reversed.

The prevailing governance requires austerity to placate the bond market, even as it also wants to promote growth to generate revenues to make future bond payments. It dismisses the possibility of climate change being a present-day issue, displacing it to a remote future. If Occupy is truly “a state of mind,” as many post-eviction banners have had it, then one way to express it would be to present a radical alternative to this neo-liberal consensus.

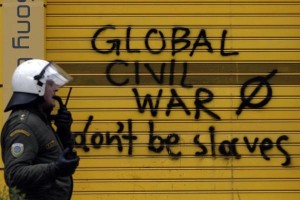

Present austerity is actively producing the societal emergency it claims to be solving from Greece to Portugal, Ireland and Italy. It seems as if bond-holders hope to recoup as much of their investment as they can as soon as possible, ignoring the future social ramifications of the crisis thereby produced. The Greek elections in April will undoubtedly be, shall we say, interesting. There are rumors from France that the National Front candidate Marine Le Pen may finish first in the Presidential elections: if she is in a run-off against the Socialist, it is uncertain that right-wing voters can be relied on to rally to Hollande. So neo-liberalism seems actively willing to gamble with the rise of the far right in order to sustain profits.

The vague hope for “growth” as a solution to the social crisis fails to recognize that all industrial and manufacturing growth at present is going to entail higher levels of carbon emissions. In New York today, I saw a cherry tree in blossom: on February 19. Yet when the New York Times published today about the impossibility of ice-fishing in Minnesota due to the thin ice this winter, the phrase climate change was not used. The deniers have pushed the debate out of the liberal mainstream.

In a report published yesterday by the Union of Concerned Scientists entitled Heads They Win, Tails We Lose: How Corporations Corrupt Science at the Public’s Expense, the list of smear and diversion tactics described is as striking as the direct connection to the polluting corporations.:

the key driver of political interference in federal science: the inappropriate influence of companies with a financial stake in the outcome…

In 2010, the oil and gas sector donated more than $10 million to PACs. The largest donors were Koch Industries ($1.2 million) and ExxonMobil ($1 million).

For this, the oil and gas industry obtained the active support of a Republican House. A larger investment will secure the Senate and independence from the Presidency.

There is a further irony that one of the few government interventions into the recession that appears to have been very successful was also one that does most damage in terms of climate change–the auto industry “bailout.” After reading the UCS report, it is hard not to suspect that the same players that have targeted climate science were comfortable letting the government support the car industry, while being happy to see that mass transit options were defeated.

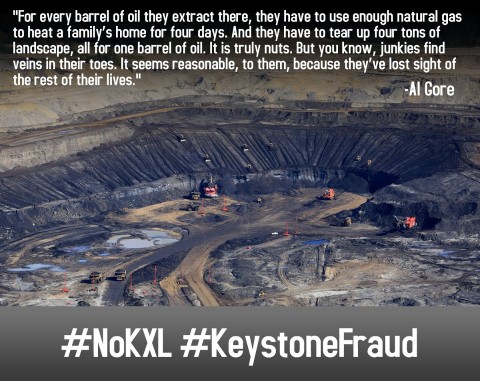

In the background lurks Keystone XL.

Al Gore has tried to characterize the tar sands campaign as “addiction,” part of the “addiction to oil” meme that is now a cliché. My feeling is that the neo-liberal corporate machine is constantly harping on Keystone not just to gain approval of the pipeline. The Canadians seem set on producing the “oil” and the Chinese will buy it, meaning that the multinationals will make their money. However, the “controversy” makes it less and less likely that the Democrats in Congress and the President will campaign on climate issues.

Therefore, any return to “growth,” the only solution that neo-liberal capital can offer, will not only be to the profit of corporations but structured around fossil fuel extraction and transport, leading to the continued success of the spectacularly profitable oil and gas sector. Mainstream liberalism nonetheless continues to believe that discussion can produce a return to what the UCS call “transparency and accountability in the use of science” and, by extension, in politics.

Occupy knows that this future is not going to happen. The future we’re likely to get is a willingness to “liquiduate everything” in the newly-fashionable phrase of depression era Treasury Secretrary Andrew W. Mellon. Fossil fuel generated growth will promote both greater climate change and further political chaos and extremism, funded by the unrestrained PACs. The Occupy encampments actively performed an alternative to that future. Other, unexpected ways have to be found to visualize it now, to make the connection between “prosperity without growth,” ending climate change and ending political corruption.