The impetus towards this project began with a piece I called “Occupy Theory,” written last October, about what the Occupy movement was doing to theory. In keeping with the moment, I kept any resolution under suspension: “Occupy theory is what you do as you occupy.” I went on to discuss Judith Butler’s talk at OWS that she later expanded and published in the first issue of Tidal, the Occupy Theory journal, under the title “For and Against Precarity.”

Those days seem strangely far away now. Here to cheer us up is the second issue of Tidal with its subtitle: Occupy Theory, Occupy Strategy. It was launched yesterday to an exuberant crowd off Grand Street in Brooklyn, where it was claimed that the interaction of theory with Occupy was one of the distinctive features of the movement. That’s an interesting idea–in many ways this project is about how you might use all the discursive practice assembled under the name “theory” for the past twenty years in the new context.

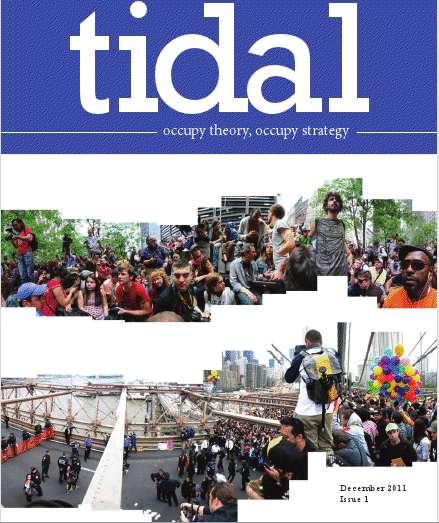

Tidal is a testament to the energies of the new movement. It’s thirty-two pages long, full color, free and 60,000 copies have been printed. Yesterday I saw people all over downtown distributing them. Inside are essays by Butler, Spivak, and Marina Sitrin, as well as by as key figures from the movement, writing collectively and individually. In this and following posts, I’m going to read the two issues against each other, measuring differences and transformations, as we gather breath for a new moment this Spring. Let’s say out loud in the affectless context of the Internet that I love Tidal, it’s a great project.

You know that there’s a difference by looking at the front covers. On the first edition (above), a panoramic montage of Occupiers at Liberty (top) and on the Brooklyn Bridge (bottom). At bottom left we can see two arrests, one woman raising her head to shout or scream. But there are photographers recording this, three we can see plus whoever took the image we’re looking at. Inside the cover, a sign reads: “I still can’t eat GDP but I can see climate change out my window.” That’s the clarity of Occupy.

The new cover is a single shot of the D17 action when OWS tried to set up a new site at Duarte Street but were thwarted by the police and the church. Almost everyone in the photograph is either a cop or taking a picture. Only a handful of people are pressing the fence that divides the image and appears to be at the point of collapse. You wonder now if a few more people had put the cameras down and pushed, what might have happened? Inside, we see a line of Spanish police with multi-colored paint on their riot shields.

In both issues, the journal opens with a “Communiqué,” a title that unusually seems to pay homage to the Weather Underground, but it may just be a coincidence. In the first edition, the Communiqué used the language of the spectacle to render the unreality of Wall Street:

We were born into a world of ghosts and illusions that have haunted our minds our entire lives…We have no clear idea how life should really feel…We have come to Wall Street as refugees from this native dreamland, seeking asylum in the actual.

The disciplinary institution this Communiqué seemed most aimed at was the university. Projects for “People’s Dissertations” and an opening of higher education to community and educationally marginalized groups argued for a proliferation of educational action:

To liberate our education must include, then, expropriating our ideas from systemic hierarchical misevaluation.

By contrast, the new edition opens with the experience of jail, police violence and a sense of breach of the social contract:

When you’re sitting in jail, the topic of justice can’t help but come up.

Jail is that which, without knowing it, we had already demanded. The figurative language is closer to Benjamin here than Debord, although no citations are given. In discussing the unnamed Thing (system or apparatus) to which we have apparently consigned ourselves in some Terms and Conditions clause, Tidal write:

The Thing resembles a ship that we’re all on together. Not a cruise ship exactly, but more of a steam ship/trawler. We have a captain who steers while we shovel coal and swab decks. …The captain stares at the impending doom on the horizon and grins ecstatically.

Here is an Ahab for the world of finance capital, one without a White Whale to hunt. Unseeing, “he uses his eyes offensively to project what he wants to see on the world.” In the academic world, this is what I have called “visuality,” the way that power visualizes history for itself and convinces us that it is right.

We might extend the figure. Moby-Dick has often been used as a metaphor for industrial capitalism with the wretched whales being dismembered to serve the modern need for light. It’s often forgotten that the most destructive whale hunting was done after Second World War, not by the sail ships, but by nations in search of cheap calories to feed war-damaged populations. The whales, social and language-using animals like ourselves, were invisible to the military-industrial machine.

The Caribbean radical intellectual C. L. R. James wrote a wonderful study of Moby-Dick, while imprisoned at Ellis Island by immigration officials. Mariners, Renegades and Castaways: The Story of Herman Melville and the World We Live In (1952) initiated a way of seeing ships both as the epitome of capitalist hierarchy, and as the site for potential and actual rebellion. It is worth remembering in this context that the very word “strike” comes from the maritime world, meaning to take down sail as a mutiny. The sailing ship was the first modern institution where the command line was instrumentalized: a highly specific technical language initiated changes in the function of the machine. Unless it crashed. Or was taken over by pirates.

The interface with present-day digital technologies is clear. As Tidal put it:

In our age, the capacity for connection, self-education and self-cooperation has exploded. This offers a window of opportunity with its unspoken, unresolved question: who will take and shape the bulk of the resulting potential?…The window will not remain open long before being overwhelmed by claims from those in power.

Here, then, is a different countervisualizing that might be possible for those of us in “jail cells, in city squares, on Wall Street, from every space we occupy,” a look out of the window, created in part by the connectivity enabled by, but not limited to, digital spaces and machines.

What might we see there?

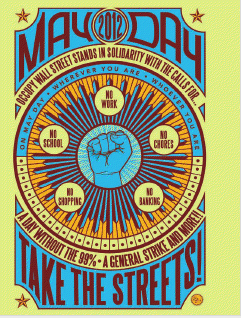

- No work

- No chores

- No banking

- No shopping

- No school

MayDay 2012.

Next: demands and horizontalism.