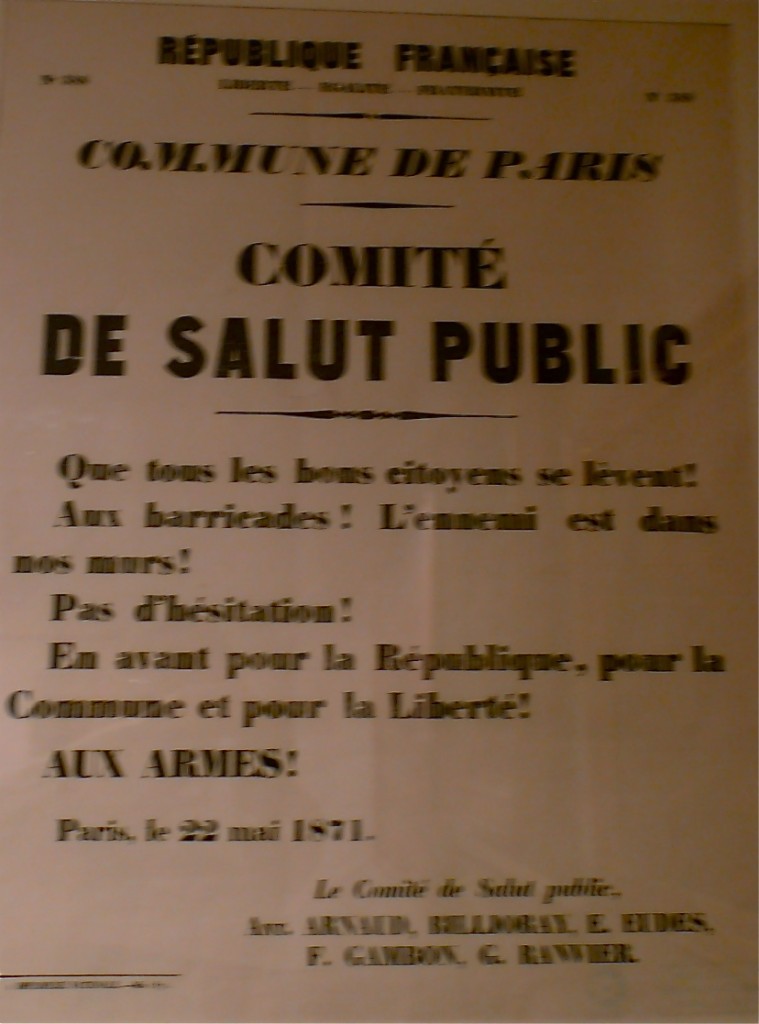

When I arrived in Paris just after the 140th anniversary of the suppression of the Paris Commune last summer, its spirit was walking the earth. The Place de la Bourse, where the French Stock Exchange is located, had been renamed the Place des Indignés, the Square of the Indignant. Or Occupy the Square, as we might now say.

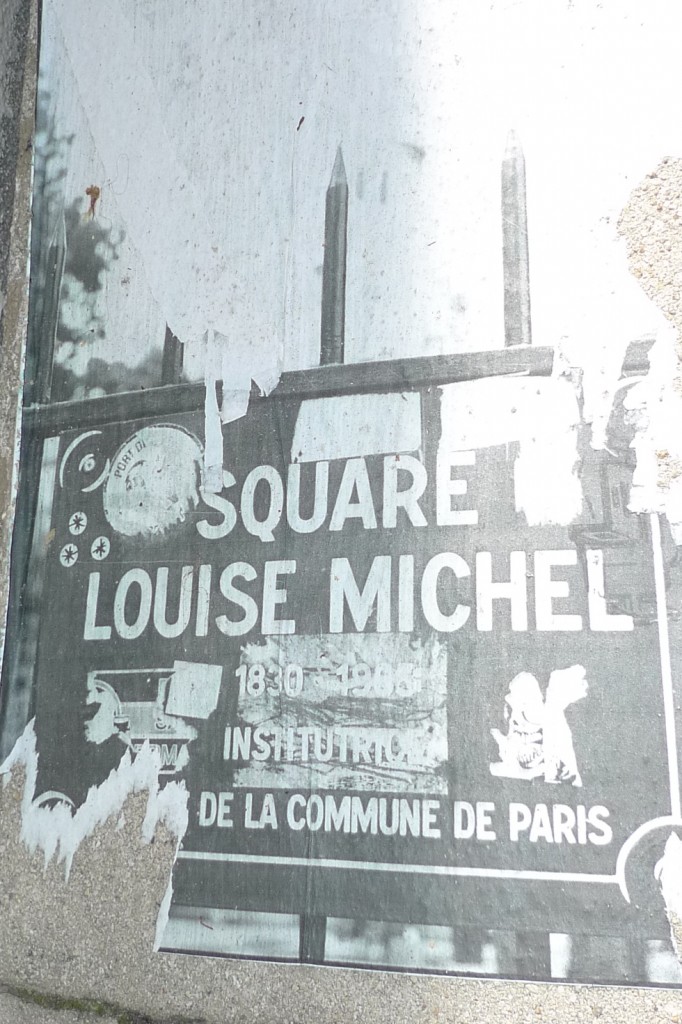

On the wide stone banister of the staircase leading up to the little apartment I had sublet in Montmartre, someone had flyposted an unusual poster. It depicted the plaque identifying the nearby Square Louise Michel–using the English word–commemorating the local hero of the Commune.

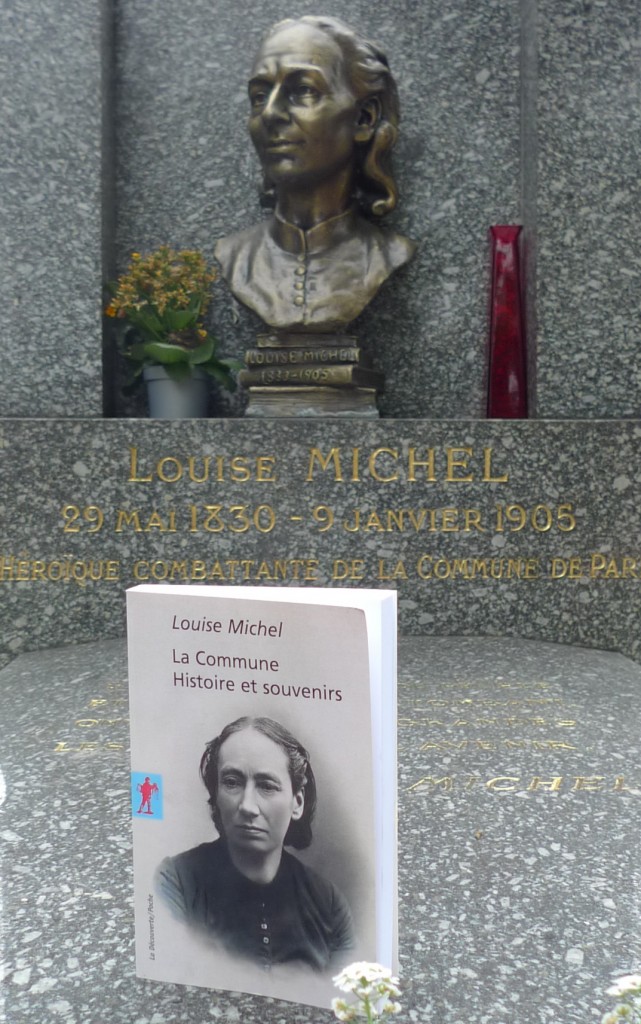

Next morning when I went out for bread, I came across this much larger poster. showing Louise Michel’s tomb–her name was clearly legible on the headstone. The quality of the printing and the flyposting was such that at first sight I wasn’t sure if it had been painted. Feminist, ant-imperialist and later anarchist, Michel was one of the best-known Communards, once known as La Pétroleuse for the false accusation that she had been a fire-bomber.

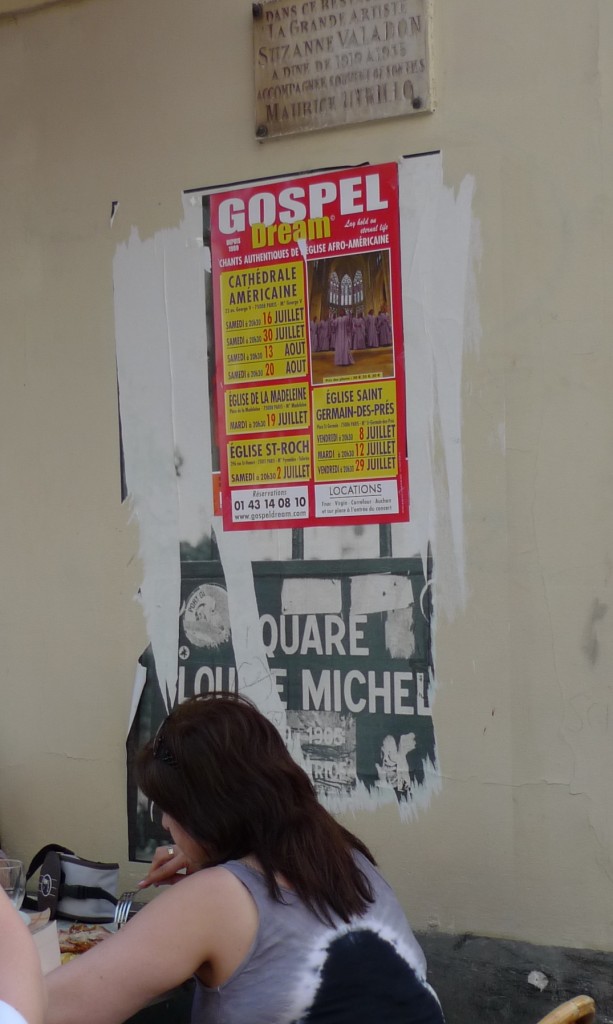

It seemed that she and her Square were everywhere in her home village of Montmartre. She lurked above the head of casual tourists, equally oblivious to the plaque identifying the house as the former home of the artist Suzanne Valadon.

From Valadon to the Gospel Dream to Louise Michel. Or the other way around? On the metro the next day, I saw an intense young man with a red beard reading a copy of Michel’s History of the Commune in a pleasingly old edition. Was this the flyposter artist? There was no way to ask, so I got off at FNAC and bought a less satisfying modern paperback.

From Valadon to the Gospel Dream to Louise Michel. Or the other way around? On the metro the next day, I saw an intense young man with a red beard reading a copy of Michel’s History of the Commune in a pleasingly old edition. Was this the flyposter artist? There was no way to ask, so I got off at FNAC and bought a less satisfying modern paperback.

Whoever he or she was, the fly-poster was all over Montmartre. I sat in the café across the street and read Michel’s account of the Commune. She described being on field ambulance duty in Clamart, to the southwest of Paris in the direction of Versailles from where everyone knew the attack would come. With her was an African man with filed teeth, who was a veteran of the Papal Guard.

Later, she sat one night and had coffee with a young student who had brought a copy of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, perhaps the “definitive” edition published after the poet’s death in 1868. They read Une Charogne [A Corpse] together, one of his most challenging poems, finding beauty in a rotting corpse. A shell descended from the enemy lines, destroying the book and their coffee cups.

There was nothing for it but to head to Michel’s tomb. A Google later and I’m on my way to the quiet and upmarket suburb where she now resides. In typical Parisian fashion, you don’t get off at the stop called Louise Michel but the next one. Here the plot thickens nicely: the photograph of Michel’s tomb used by the fly poster is revealed to be antique. The splendid flowers are perhaps the gift of the trade unions who bury their leaders in the same corner of the cemetery.

So I left my book as an offering. The spirit of the Commune was alive and well, occupying her old haunts. Michel was no spectre, nor a phantom, or one of the frightening revenants. I don’t think Michel was as gentle a spirit as a fairy, who tend not to carry Remingtons. Although oddly, Benjamin’s first subtitle for the Arcades project was A Dialectical Fairy Play. Michel put her body in harm’s way, knowing full well what was coming and her spirit survived then and now. Remember her.

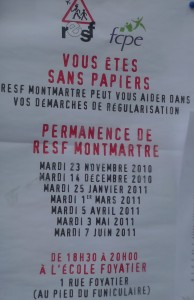

In the streets of Montmartre, the unsung heirs of Michel’s ideas were still in action, getting ready. Regular meetings were being held to help the undocumented regularize their situation.

Vive la Commune, one hundred and forty-one years young this week, long live the common!