In remembering the general strike we also need to remember the historical world-view of the general strike. We have to replace the idea that all progress was modern and Western with a decolonial perspective that reshapes time as well as space. We should set aside the fictitious genealogy that runs from ancient Greece and Rome to Christianity and then modernity, even in thinkers as profound as Foucault, with an awareness of how much more varied and interesting the historical record has been.

So let’s consider the ancient world with this in mind. The oligarchic “democracies” of Western Europe and North American in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries first defined themselves as descended from ancient Greek democracy, a rhetoric that is widely deployed today. Against that pose, anarchists and radicals of the period produced a history of the ancient general strike.

Athenian democracy was in any event nothing like our present-day representative system. It was limited to non-slave men of adult age who had completed military service, a minority of approximately 10% of the population of Athenian slave-labor society. Most free Athenians “owned” at least one slave. Within the structures of the Assembly, officials were selected not by voting but by lot, on the presumption of equality. So while the Assembly proceedings were decided by majority vote, this was a direct democracy of the minority, contrary to the usual representations. A look around any Western capital city will confirm that ancient Greece and Rome nonetheless became the archetypes for the modern imperial capital.

By the same token, European and North American radicals identified themselves as the descendants of Roman slaves in ongoing resistance to classicizing aristocrats. So the proles (child or minor) of Rome had engendered the “proletarian” of the industrial revolution. These researches into ancient class struggle were, according to History Workshop scholar Raphael Samuel,

the principal site on which the claims of historical materialism were advanced.

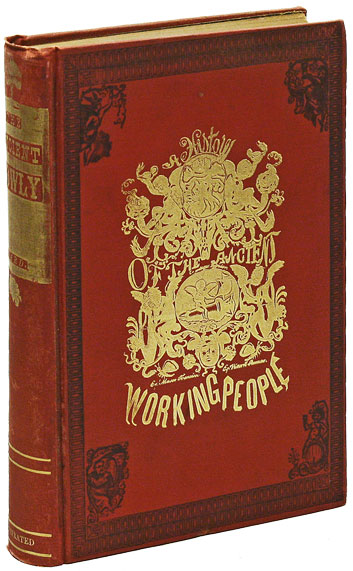

Among the most influential of these publications was a remarkable two-volume opus called The Ancient Lowly (1888) by C. Osbourne Ward, a member of the New York based People’s Party.

Ward did extensive original research in keeping with the then-latest methods of studying ancient inscriptions. In all other ways, he broke with academic convention. He self-published and later worked with co-ops to get his work out. He described his findings as “news,” like today’s “history of the present.” He called attention to ancient rebels and resistance fighters like Eunus, Achaeus and Cleon, who led what he called “general strikes” against Rome. Cleon, for example, headed an army of 200,000 rebel slaves in Sicily around 140 BCE. Under Eunus the formerly enslaved dominated the entire region for over a decade from 143-133 BCE, defeating numerous Roman armies.

You probably still haven’t heard of these people but you have most likely heard of Spartacus (109-71 BCE), revolutionary leader of the enslaved. His story was told in the classic movie from 1960, directed by Stanley Kubrick and starring Kirk Douglas as Spartacus. Now the film is mostly remembered for its camp homoerotics and for the claim by all the captured rebels: “I am Spartacus,” a form of mike check.

There’s a sex-and-sandals TV show about Spartacus out in the wilds of cable-land even today.

These popular culture forms are the cultural echo of the long radical tradition of seeing the ancient period as one of radical class struggle, in which the enslaved often won victories against their oppressors. Indeed, seen in the historical long-run, you might argue that they won outright. Around 600 CE, slavery disappeared from the former Roman Empire in the West. While there are many views as to the cause, the modern radicals would have had no doubt that it was the final victory of a seven hundred year struggle. Against the view that slavery had existed everywhere prior to its European abolition, this argument can point to eight hundred years without slavery from c.600-1492. With such perspectives in mind, early twentieth century radicals recast the Bliblical story of Exodus as the Israelites general strike against dictatorship.

So how do we know that another world is possible? Because people have remade worlds over and again, overturning hierarchies that were supposed to be divine and eternal, first for days and years, then decades and centuries.

Exactly my thought Douglas–I wanted to add this political context to Graeber’s fascinating comments about the introduction of money–a political economy, in short, for this first abolition of slavery.

The disappearance of slavery in the Middle Ages is well worth noting. It is featured prominently in David Graeber’s *Debt: the first 5,000 years* (pages 211–214). It was not limited to Europe, but occurred worldwide, and was related to a shift from cash to credit transactions.