Occupy theory is what we do as we occupy or as we create a relation between democracy and capitalism. That relation is dynamic and unfolding. It has moved from a place of critique and the articulation of grievances to a call for abolition. In so doing, OWS is creating a set of pasts for itself that predicate possible futures, a temporal version of the prefiguration that direct action embodies. However, this prefiguration does not take place in a context of our own choosing and so direct democracy has been driven to consider the terms of its own possibility.

I’ve been arguing here for a while that abolition and Reconstruction provide one such past because slavery was an economic system predicated on debt that was reconfigured by the formerly enslaved into new forms of sociality that we can learn much from.

So I’ve been reading the Proceedings of the South Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1868 (available oddly enough as a free Google book via something called Google Play, which seems to be yet another of their efforts to make Google cool). The Convention was charged with drawing up a new State constitution in light of the Reconstruction statutes and to bring the State into line with the Union. Most whites boycotted the election for the Convention, with the exception of anti-slavery people and some cannier former Confederates seeking to limit the damage.

It’s an amazing document, over a thousand pages of debates, motions, discussions. It has a distinctly familiar feel. There’s a great deal of discussion about process. A lot about money. And they ended up renaming the meetings of the Legislature as the General Assembly, which is still their name.

By far the longest discussion is about debt. More precisely, whether debts contracted by those selling and purchasing slaves during the war had to be honored. What had happened was not extensive slave trading as such, but the mortgaging of the enslaved to raise money for the Confederate war effort. There were thousands of such debts outstanding and creditors were trying to sell the plantations in order to recoup some of their debt. In the post-war recession with no established labor systen, land was very cheap and these sales would not in many cases have raised enough to clear the debtors. They would, however, have provided an opportunity for the freedmen (as they were known at the time) to purchase land and establish an economic foothold.

I don’t think it’s too much to see this as a determining moment for future US history: had the plantations been broken up and a communal agriculture been established in what was the most radical of the Reconstruction states in precise relation to South Carolina’s enthusiasm for slavery, very much would have changed.

The debt was first proposed to be frozen, or, as its opponents put it, granted a stay. The transparent hope was that three months later, if the Union army had departed, the debts could be quietly forgotten. Delegates rejected this by a large majority. The motion was reframed as if motivated by anti-slavery sentiments. Now the argument was that, as there is no “right of property in man,” no debt could be incurred, as that which was being mortgaged was not owned in the first place.

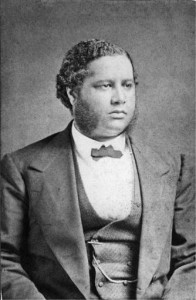

One of the most eloquent opponents of this slaveowners’ debt annulment was the Rev. Francis L. Cardozo. Cardozo was the son of a free black woman, Lydia Weston, and a Portuguese-Jewish man, Isaac Cardozo or his brother Jacob. Between the ages of five and twelve he attended a school for free blacks, then he spent five years as a carpenter’s apprentice and four more as a journeyman. Cardozo then worked as a carpenter and a shipbuilder. In 1858, he attended the University of Glasgow in Scotland where he graduated in 1861 and later became a Presbyterian minister.

Cardozo described the debt annulment as a “class measure,” to protect the slaveowners. As he pointed out, they had known the “precarious tenure” of slavery when they took on the debt. More importantly, he saw this as the only chance to break up the “plantation system.” He described how a hundred freedmen in Charleston had formed the Charleston Land Company. Buying shares individually, they had collectively just bought 600 acres of land for $6600 that would formerly have sold for $25-50,000. Cardozo declared:

Men are now beginning not to plant cotton but grain for food, and in so doing, they are establishing a system of small farms, by which not only my race, but the poor whites and ninety-nine hundredths of the other thousands will be benefitted… [Planters] do not want that a nigger or a Yankee shall ever own a foot of their land.

Perhaps this is the first use of the 99% meme? It envisions a future of sustainable local agriculture rather than single cash-crop agribusiness cultivation that is again being promoted today by food activists, environmentalists and de-growth economists.

But Cardozo and his allies lost the vote to a majority comprised of African Americans opposed to slavery in all forms and self-identified “whites.”

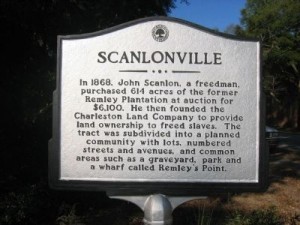

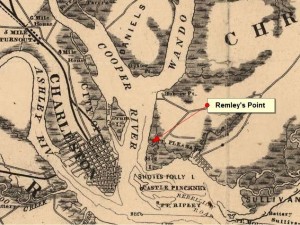

The Charleston Land Company did nonetheless succeed in creating a community, now known as Scanlonville, in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, after its leader Robert L. Scanlan (or Scanlon). The land formerly belonged to a plantation called Remley’s Point, a name still used by local realtors. First settled by Seewee Indians, the site was colonized by the British as early as 1680.

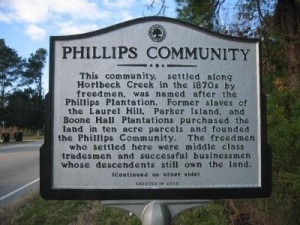

In Scalonville, the freed bought the land in parcels and then redivided it into farm plots and town plots and has remained in place since Reconstruction, one of four such collectives in the state.

However, the African American population of Mount Pleasant is now less than one percent and the community is now threatened by the expansion of sub-divisions into suburban Charleston, subject of a 2010 documentary. Bin Yah (Been Here): There’s No Place Like Home (2010). The name comes from the Gullah language derived directly from African languages, spoken by the formerly enslaved and still in use today.

Here’s the beginning with amazing old footage of a plantation and slave cabins and proceeding to an interview with Queen Quet, Gullah-Geechee Nation Chieftess:

What does this all imply for the Strike Debt campaign? First, that there is a huge precedent for debt abolition, albeit one that we might not feel terribly comfortable with. However, it was in effect a prefiguring of the modern usage of “odious debt,” a debt created by a situation so morally repugnant that it cannot be enforced. That’s why most of the African American delegates voted for debt abolition. Three years after the end of the war, it’s not hard to see why nailing slavery’s coffin shut was so important.

At the same time, the project of getting land to the landless and establishing a democratic economic system was equally important to achieving a long-term freedom and that did not succeed. The exceptions like Scalonville show that it could in fact have worked. So what matters now is not just getting debt relief/abolition but having a project with which to replace the system that created debt in the first place.

Pingback: Bring Back The Just Price! | Occupy 2012

Pingback: Reconstruction at Work | Occupy 2012