How can we imagine the Anthropocene? Industrial capitalism is not simply harmful to human life, as we long knew, but has created its own geological era that affects everything from the lithosphere to the upper atmosphere and all the biota in between. Indeed, the dynamics of the Anthropocene are increasingly hostile to Holocene-era patterns of human life, a footnote to the sixth great extinction of carbon-based life.

Estimates suggest that between 17,000 and 100,000 species are becoming extinct every year. The Anthropocene is perhaps not so well named. While it is clear that humans have caused it, not all humans have done so and its consequences are far from even. What has brought about the change in planetary geology is industrial capitalism and its reliance on fossil fuels.

We now find ourselves confronting what we might call an autoimmune capitalism that seems determined to extract the last moment of circulation for itself, even at the expense of its host life-world. Like AIDS or other autoimmune disease, this capitalism has a long etiology, multiple symptoms and is resistant to cure: Autoimmune Climate-Changing Capitalism, AICs for short.

So if we concentrate on curing one symptom, like carbon emissions, the complaint goes up that we are attacking the “Western way of life.” Attack the over-consumption of Western life directly, as the global social movements have done since 2011, and you find the full force of the military-industrial police complex directed at you.

To put this more abstractly: coming to terms with AICs is a political problem that is also always and already an aesthetic one. Aesthetics here means the ability to feel or perceive and I am suggesting in the manner of Jacques Rancière that no politics that is not an aesthetics (and vice versa) can have purchase on the supplementary, non-linear and networked forms of AICs. In short it takes a supplement to interact with a deconstructed form. Luckily, we already have that supplement in the form of direct democracy, which is my update to Rancière’s notion of the an-arche of the demos.

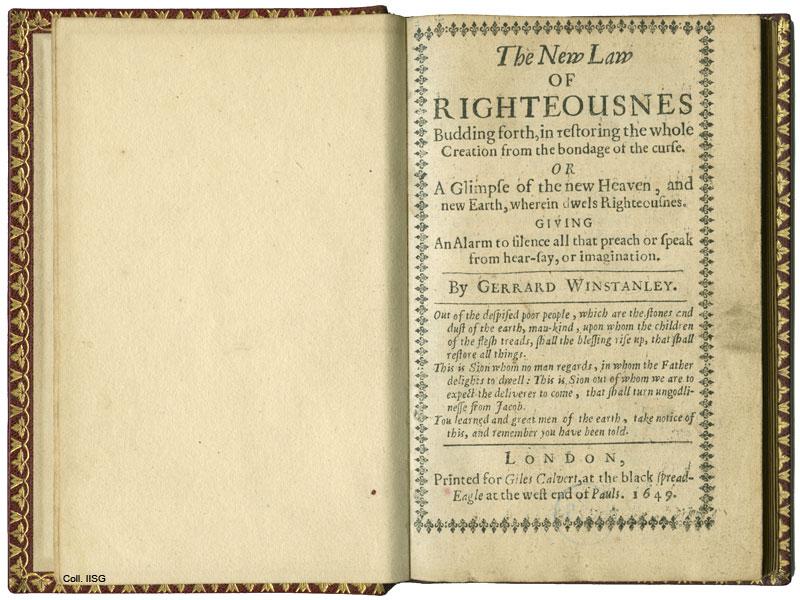

This is usually the place for lamentations about the difficulty of doing anything against the modern Leviathans of multinational corporations, consumerism and the fossil fuel industry. I do not underestimate these forces. However, I do not participate in their visualization of the planet as a battlefield and presume that in order to return the world “upside down,” they must somehow be defeated. Rather I think that the reclaiming of the imagination entails an undoing of their authority, which they themselves literally cannot conceive. It may come from the Digger Gerrard Winstanley’s evocation of the “earth as a common treasury for all.”

I have long said that the most radical gesture would be if all living people were considered fully human. That could be taken further to include all non-human actors. It has been estimated that some 90% of the DNA in our bodies is not “ours” but microbial. “Our” DNA is the result of a long sharing between generations. We also now know that certain “switches” in the genome are turned on by experience—diet, toxicity, age, and so on.

Taking this for the metaphor that it clearly already is, we might say that there is a “switch” for the common. Much of the past five hundred years has been devoted to imagining ways to turn it off or even make it invisible. In the brief time since Mohammed Bou’azizi shocked Tunisia into taking action by his self-immolation, that switch has proved remarkably easy to find from Egypt to Montreal by way of Madrid, Athens, New York, London and so on. We have in effect always known how to do this. Authority has invested enormous amounts of energy, time and money to convince us otherwise.

Some proposals for an agenda:

1) Life

The right to existence was the fundamental claim of all anti-slavery movement. It is the first claim in the Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth made at Cochabamba, Bolivia, in 2008 by the World People’s Conference on Climate Change as part of their claim for the “decolonization of the atmosphere.”

2) The Land

Policy specialists have began recommending small-scale collaborative cultivation as a solution to developing countries economic needs. Local food movements suggest the same for developed nations. The Cochabamba accords recommend such cultivation as the key to both sustaining indigenous cultures worldwide and decolonizing the atmosphere. With the agribusiness GMO corn crop set to fail in the U. S., we can see that chemical cultivation is no guarantee of food supply in the climate-changed era. Land is a way to consider the abstractions of the global in local contexts, as it has been for centuries.

3) Democracy

The greatest myth of the climate denial movement is that we can’t do anything about this anyway, so why try? I earlier suggested in this project that if each of 400 global cities consensed on the measures taken by Beijing during its Olympics we could in fact meet the target for climate emissions reduction that would limit temperature rise to two degrees Celsius. There are other possible ways to do this of course. In other words, the choices are there in front of us and it is up to us in each of our localities to keep putting them to our local assemblies.

[a condensed version of my contribution to the Sense of the Planet symposium yesterday in Sydney]