Here’s the outline of an art history told from the point of view of debt. I devised this for a session of Occupy University held in an art gallery and at first it was just a bit of a joke but it came to seem that you really can tell the history of canonical Western art as a story about debt and commodification.

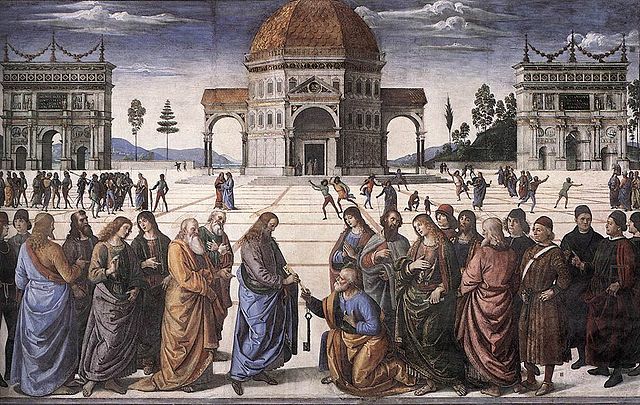

This painting by Perugino is typical of the transformation of pictorial space created during the Italian Renaissance, which is when the classic “Renaissance to Modern” art history survey class begins. Perspective depends on drawing all lines to a vanishing point, in this case located in the door of the church. This visual element reinforces the meaning of the painting in which Christ anoints Peter as the leader of his “church” to come. Visually, it depends on a space of nothingness, the vanishing point.

At the same period, this nothingness came to be drawn as zero, using the Arabic numeral ‘0’ for the first time. During the Middle Ages, zero was considered immoral precisely because it represented nothing, whereas God was everywhere and so there could not be a space of nothing. By the same token, interest, money that comes from nothing, was immoral. Zero was then instrumental both to the system of visual representation and the emergent capitalist banking system based on debt that paid for it.

Jumping ahead as we do in these rapid surveys, here’s a classic seventeenth century Dutch still life by Klaesz. It represents a debt financed economy on a set of levels. First, it depicts a group of commodities, including exotic imports like olives and lemons from the South of Europe. The pocket watch represents both advanced technology and the new importance of accurate time to commerce. Second, the audience is taken to be those people who know what these things are for and how to use them–even today proper use of cutlery and glassware in fine dining restaurants is very intimidating. So it reinforces the cultural as well as finance capital of the painting-owning class. The painting is itself a commodity, of course, and it indicates the patron’s refinement that he can afford this level of technical skill. In short, the painting creates a reality-effect in which speculation and the commodity are taken as the material basis of the concrete.

John James Audubon, the ornithologist, by contrast turned from debt to natural history. Exiled from Saint-Domingue (modern Haiti) by the 1791 revolution, Audubon later started a mill in Kentucky but went bankrupt during the financial panic of 1819 and was imprisoned for debt. On his release, without any money, he decided to travel down the Mississippi and draw birds. Audubon had then gone through the collapse of two economic systems before learning how to sustain himself in the emerging knowledge economy of the nineteenth century.

The history of modern art is nothing but the history of debt: indebted artists desperate to sell work, bankers and financiers becoming their dealers, other bankers and financiers buying the work. Above is a portrait by the independently-wealthy Manet of the banker-turned-art-dealer Duret. There’s a little miniature still life at bottom right as an acknowledgement that the painting depicts the new world of commodities and capital, in its mix of seventeenth-century Spanish Absolutism (via Velazquez, the grey background, the painterly style) and the painting of modern life (via Baudelaire, the depiction of modern dress and the bourgeois).

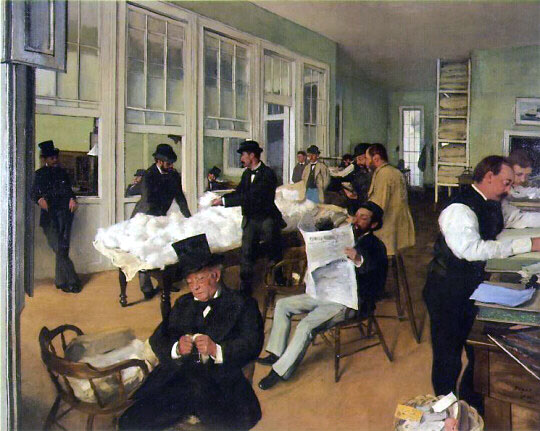

Here’s Degas, son of a banker, painting his uncle the cotton speculator in his New Orleans office during Reconstruction. The people in the room are in debt because they lent money to the Confederacy during the Civil War. They’re about to rise up in support of “Redemption,” meaning white supremacy and the end of Reconstruction. Fittingly, the scene is dominated the white whiteness of the cotton itself, for which so much blood and tears were spilt.

Sargent paints the wife of a banker. A scandal ensues. Not for the first or last time, a woman becomes a debt-financed commodity.

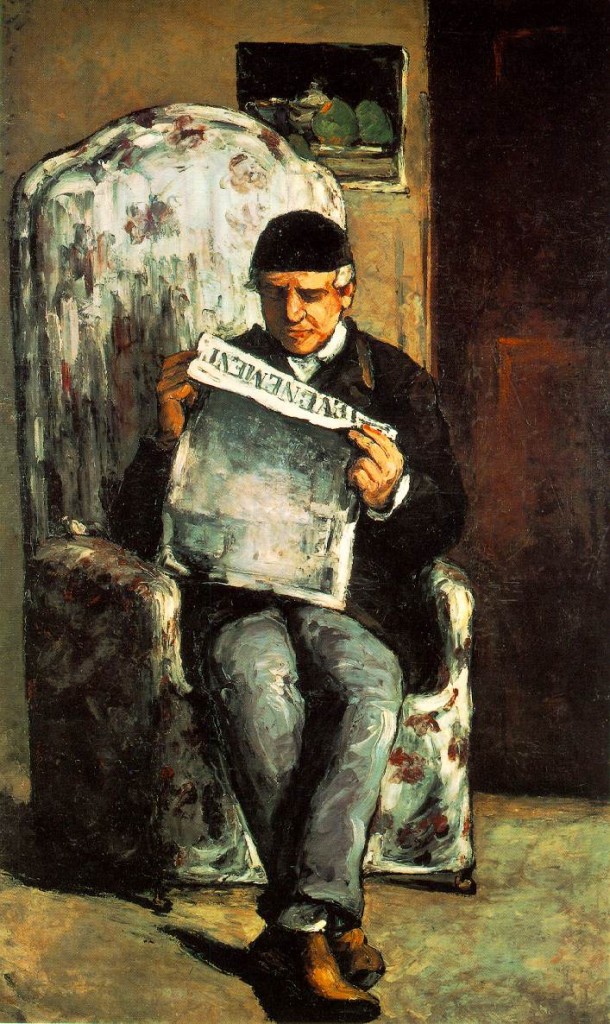

Here’s Cézanne’s portrait of his father, a banker, reading the newspaper to see how his affairs are going. Patriarchal debt-financed authority here literally enabled the avant-garde.

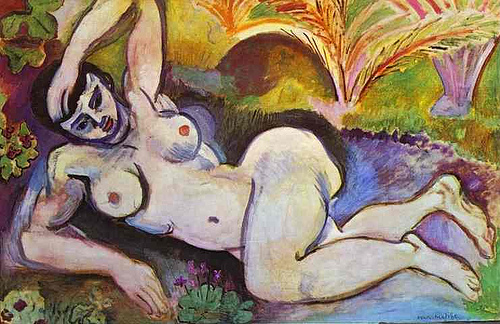

Finally, a place where it all comes together. Matisse said of his work that he wanted it to be

an armchair for a tired businessman.

What it shows is a woman from the North African town of Biskra, a French colony, who we are supposed to think was a sex worker. So calling her a “souvenir” has the usual bought object connotation and the sense of a fantasized memory–the real woman did not have hips like that, for example. It’s colonial speculation at work–business–interacting with the sense of entitled play and commodified heteronormative desire to create the new normal of the imperialist world-view.

These paintings are not “just” about debt or just explicable by debt, of course. There is nonetheless a coherent way to tell the story of Western art from the zero of perspective to the emergence of the debt-financed dealer and today’s speculative global art market that is informed by the rise of the debt society. I wonder if anyone’s going to teach it?

Pingback: How To Change: Learning, for example | Occupy 2012

Let’s do it! open access, free on demand, unlike the $200 sales catalogs that are art history textbooks:)

Aht history needs to completely reweitten and here is a large part of the reason why.

Pingback: The Art History of Debt