Occupy 2012 has decamped to Europe for a few weeks, from where I’ll be reporting back on the response of the European movement to the crisis and what’s been going on in New York. So have a happy Thanksgiving everyone!

For the present, I’m in London, where I grew up. Most of the city landmarks by which I oriented myself–cafés, clubs, record shops, book shops–are gone now, leaving me to discover a city that resembles the one I knew but feels strangely different. The resonance has changed.

Although there was a passionate student demonstration just yesterday, it feels less tense here than New York. Perhaps because there hasn’t been a devastating hurricane. Or perhaps it’s just because, living downtown as I do in NYC, I feel the resonance of all the past year’s conflicts everywhere I go but don’t get them here.

Tiqqun, the French collective that authored The Coming Insurrection in 2009, suggest that “movements do not spread by contamination,” but by “resonance” between radical moments, and that is certainly what we have seen with the upsurge of popular resistance in recent years. As I’ve often argued here, feeling those resonances is crucial to building and growing a movement.

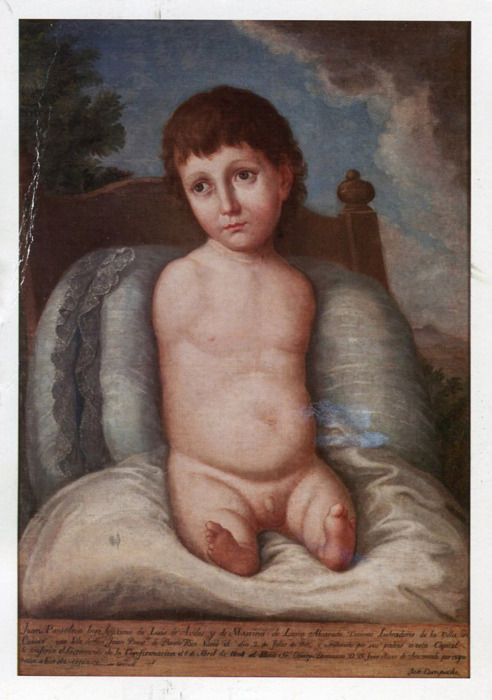

However, in academic, let alone journalistic, contexts such an approach is ruled out of court. Academia remains tied to a positivist system of evidence. For example, I write about a Puerto Rican painter called José Campeche, who was the son of an enslaved artist. His father bought his own freedom and Campeche worked for governors and bishops. But when I see influences of African syncretism in his work (meaning that there is a “hidden” but visible reference to African beliefs), I am always asked for “evidence” beyond what is in the image.

So this extraordinary painting of a dis/abled child is described by catalogs as being of scientific interest. Only it’s a full-size oil painting not a black-and-white drawing and the awareness displayed by the child far exceeds what the actual two-year-old might have been expected to display. In Central African belief systems, certain spirits called tohusu can manifest as dis/abled children. This resonance is there in the painting and thousands of enslaved Africans from Kongo had been brought to Puerto Rico around this time, who would also have “seen” it. It seems that inferred influence is allowed only within the confines of the (white) canon.

It seems like a labored way to make the point but that’s what happens: you get drawn into extensive discussion of specific details and lose the wider picture that you are trying to convey. Of course, for academic realism, such a picture can only be built by the accumulation of such building blocks of documented detail.

So it was a pleasure to read Charles Darwin, author of perhaps the most influential history of resonance, The Origin of Species. Darwin points out that the fossil record is incomplete and that it is absolutely impossible to reconstruct the precise genealogy of variation within species. But nonetheless, he noted that the naturalists of his time:

win their prizes by selecting such slight differences, yet they ignore all general arguments and refuse to sum up in their minds.

Darwin was sure of the idea of evolution in 1844 but waited until 1859 to publish it for fear of the critics.

But of course it’s the Origin that we remember, just as a book like Graeber’s Debt will long outlive the nitpick-fest that has followed its publication. So without comparing myself to these two giants, I intend to see what can be learned by resonance over the next few weeks in the expectation that it is the means by which we can countervisualize against the “common sense” of the mainstream.