In her essay in the new Tidal, Gayatri Spivak encourages us to develop what she calls the “will to justice.” This ethical and incremental approach is at odds with what I might call the palpable “will for hierarchy” within certain sectors of the movement. The desire for “wins” sometimes risks overshadowing the very radicality of Occupy’s challenge. For to be theoretically anti-hierarchy is always and already an organizational imperative–“be the change that you want to see.”

Gayatri Spivak

Spivak’s call reworks Nietzsche’s famous phrase “the will to power” that was so significant for thinkers like Michel Foucault. In Beyond Good and Evil, for instance, Nietzsche defines

our entire instinctive life as the development and ramification of one basic form of the will–namely, of the will to power.

Such power, Foucault argued, is not owned or controlled but simply used. It was a challenge to then-dominant ideas about the “conquest of state power” because power would continue to be instrumental, regardless of who was directing it. Spivak also turns away from such “vanguardist” approaches, as she calls them, in favor of

the general nurturing of the will to justice among the people.

There are three distinct threads interwoven in this phrase. Spivak’s mind is so supple that you can visibly see her thinking on multiple levels simultaneously as she speaks. Here she mixes Rousseau, Derrida, feminism and Marxism.

From Rousseau, we get the concept of the “general will,” the base on which social order can be constructed. Nick Couldry and Natalie Fenton have shown that

The Occupy movement is an attempt to form the general will in new ways. As such, it is a potentially fundamental contribution to resolving the contemporary crisis of democracy….as a part of saying yes to the possibility of thinking differently about the political consequences of global markets

That is to say, the “counter-democracy” of saying no–to Republicans, to war, to neo-liberalism–has been joined by a means of saying “yes” to new forms of community and democracy. “Nothing can be harder than this,” caution Couldry and Fenton.

Yet Spivak gives the process an optimistic tinge. She links Rousseau to Derrida’s concept of “justice” as that which cannot be deconstructed. Which is not to say it is a simple thing. As the global movement knows, Derrida’s justice

doesn’t wait. It is that which must not wait.

But at the same time,

justice is an experience of the impossible.

Otherwise known as the impossible demand. The will to justice is the deconstruction of the force of law. It is the right to look.

Because the right to look is a consenting exchange between two (or more) it is by definition non-hierarchical. It is also, as Spivak stresses, the responsibility to nurture and care for the other: what we call mutual aid. Emphasizing the feminism of the will to justice, Spivak recasts its imaginative horizon from war or struggle to care and nurture.

With all these concepts in action, Spivak is able to re-energize the much-abused formula of “the people.” It’s important to note that she does so in a planetary framework that emphasizes how neo-liberalism relies on global hierarchy to function:

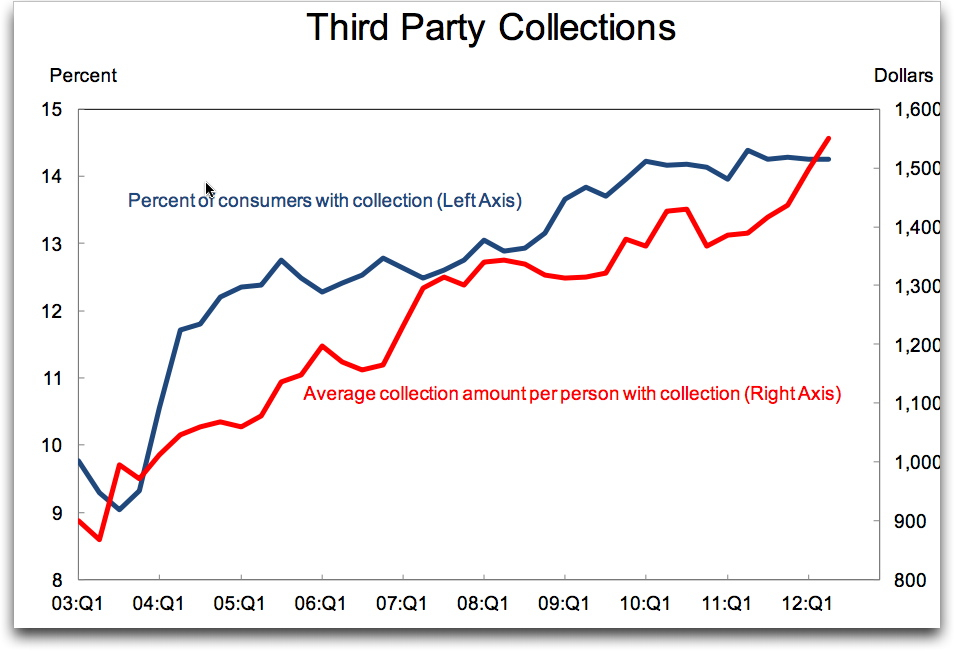

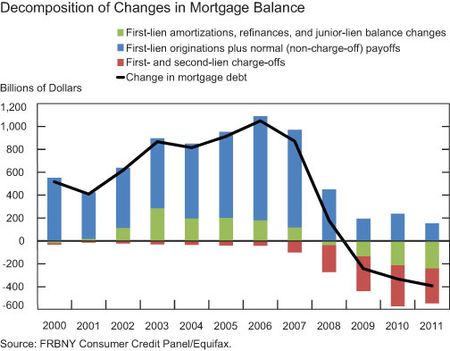

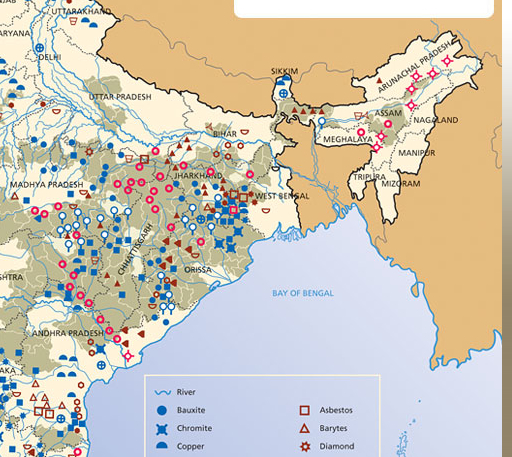

For financial globalization to work, the world must remain unevenly divided between the global South and the global North, so that there can be constantly fluctuating differences in the value of hard currency and soft currency, so that financialization can operate.

It’s crucial, then, not to replicate this hierarchical “world-making” in our own organization. In addition to this theoretical caution, we also need to be careful that a strategy that produces gains in the global North does not do so at the expense of the South.

It’s easy to be solipsistic here and say, for example, “a win for the Democrats is a win for the South,” even though it’s simply marginally less bad. Take the case of the Marikana platinum miners. While we want to support their claim for a living wage, it must also in the long run be better that they not have to work as miners, both because the labor is so hard and destructive; and because that would mean fewer cars were being built, as platinum is mostly used for catalytic converters. But were that to happen overnight, the result would just be more poverty.

For as Suzayn Ibrahimian puts it on the facing page of Tidal:

We have fundamentally understimated our ability to recreate our own oppression.

She sees the widely-circulating concern with “wins” as a short-term viewpoint that reinforces the “hierarchy of stability.” And so people more or less openly call for vanguardist approaches in OWS, or what are euphemistically called “decision-making bodies.” Of course this could be done and then we would be one more lefty pressure group, hoping that for some reason the Democratic Party might finally change its mind.

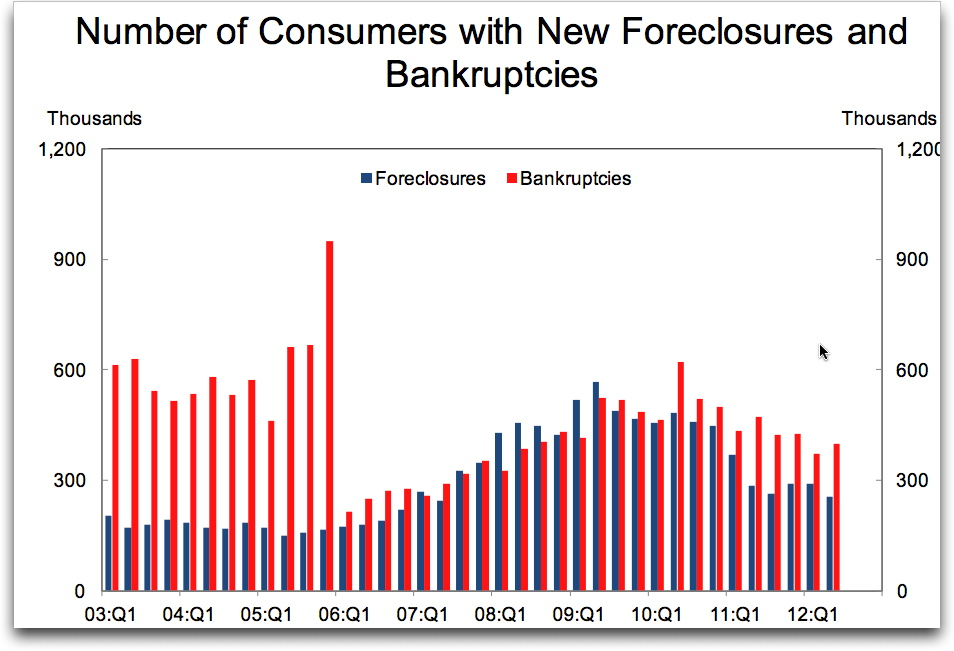

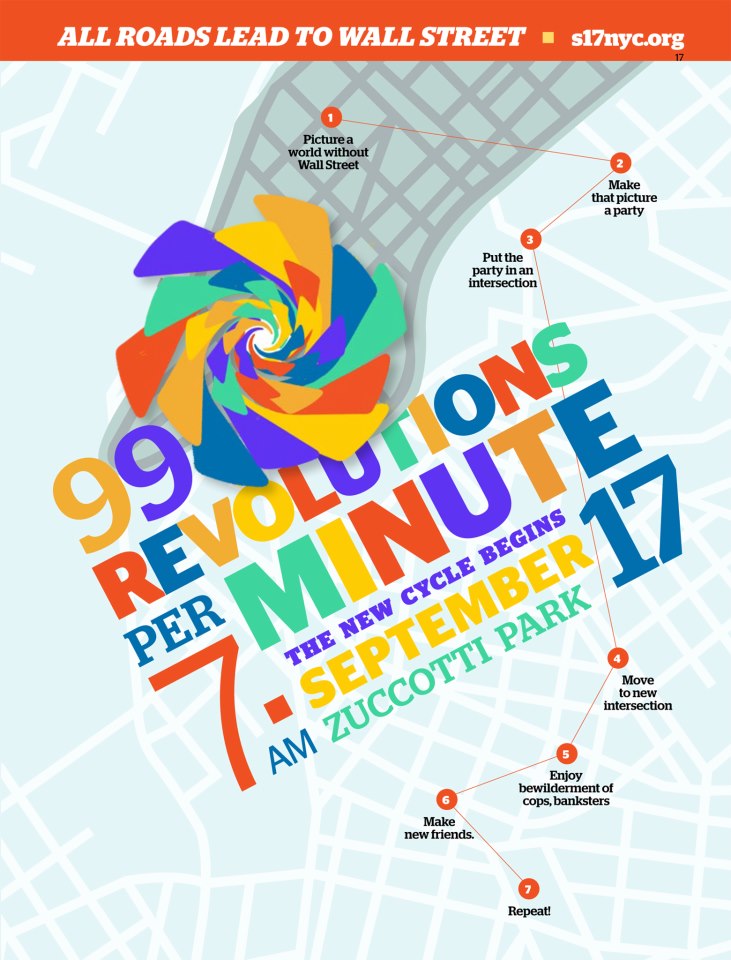

It seems that “Occupy” is about to splinter into a coalition of broadly autonomous campaigns like Strike Debt, Occupy Our Homes and Foreclose The Banks that come together for symbolic days of action like S17. If this means of organizing preserves the will to justice that was so visible a year ago, rather than creating new hierarchies, then let’s make it happen.

To return to Spivak, it is only the

building up of a will to social justice

that matters, not the name under which it is done.

Like this:

Like Loading...