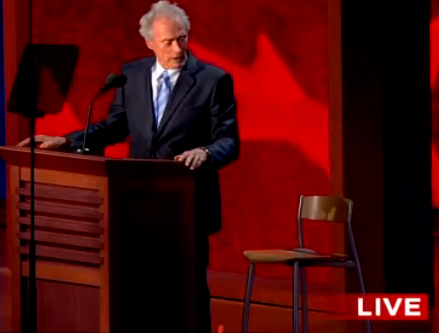

Today I went past a noisy and aggressive Tea Party roadside rally in Setauket, New York. The people were all white, all over 50 and all angry. In other words, they were the Clint Eastwood audience. As apparently crazy as that performance was, it articulated very clearly the vivid resentment middle-aged white people feel and direct towards the empty space they call “Obama.”

I refused to watch a moment of the Republican convention, just as I will ignore the Democrats. There was something about the stills of Eastwood’s performance that made me watch the video. Although it has suggested avant-garde performance art to some people, it was clearly designed to appeal to those with long memories. As a number of reporters have suggested, the whole chair routine was a steal from the circa-1950 comedy of Bob Newhart and Morey Amsterdam. There’s also a certain inherent period nastiness to “the chair,” evoking as it does the electric chair so favored as a method of execution in the Cold War era.

For this evocation of time and place was specifically designed to reinforce the aura of white privilege that surrounds Romney but to give it a more violent edge. Eastwood’s Gran Torino performance was remembered by the Republican audience for its initial racism not the feel-good “liberal” conclusion. Not once but twice, Eastwood ventriloquized Obama as saying “go fuck yourself” to roars of approval–clearly Obama’s refusal to play “angry person of color” nonetheless angers this kind of white person.

The moment in the video that resonated with the apparently all-white crowd was when Eastwood said

You own this country.

It’s a standard bit of political boiler-plate from a professional but from an actor associated with vigilantes and outlaw cops, it had a different affect. They heard it as saying “this is still a country for white Christians with guns as it has been since the arrival of Europeans.” So when the crowd chanted with Eastwood at the end

Go ahead, make my day

it was an enactment of an NRA fantasy moment.

The Democratic media have seen the affair as a joke. For Jon Stewart, this was the greatest gift since Dick Cheney shot a man in the face. But Stewart was not just being funny when he said

There’s a President Obama only Republicans can see

Obama serves as a screen for white people to register what they think about “race,” meaning the visible presence of any non-white person in public life. For 50s-nostalgic Republicans and reactionaries of all kinds, the proper place of the person of color is as what Ralph Ellison famously called “the invisible man.” This “Obama” knows his place, and can be put down at will if he gets “uppity.” Into his (baby) chair.

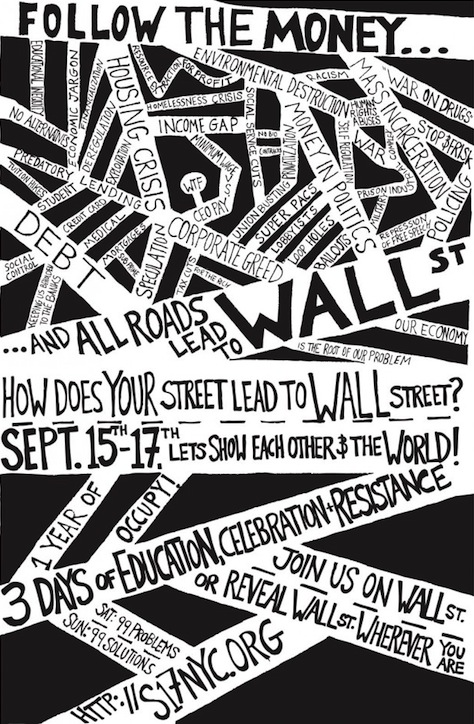

I am not particularly invested in the re-election of Obama, other than as being preferable to the alternative. The “Obama” that Eastwood and his acolytes see, however, is genuinely disturbing. It’s why Bloomberg gets away with stop-and-frisk. It’s why the economic crisis has wiped out a generation of wealth accumulation by African Americans and left them not only disadvantaged but being blamed for the crisis. It’s why police can use violence at will against Occupy and have no fear of reprisal. Oddly, we should perhaps thank Eastwood for making all this visible to us once again.