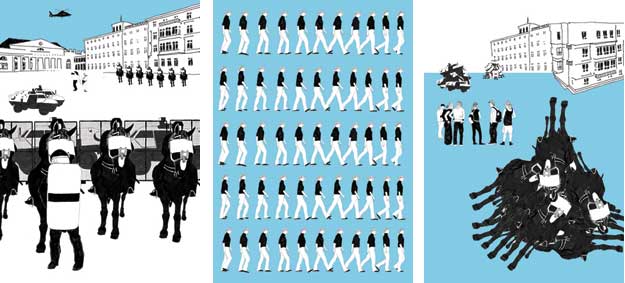

Throughout the course of the global social movement, there has been a serious question as to legitimacy and the place of violence. When Tahrir Square was filled with revolutionaries, it was clear that Mubarak was no longer legitimate. There has been an extensive, if not terribly productive, discussion in Occupy about “diversity of tactics.” Now the situation has become tragic and farcical at once with the absurd statement of so-called “Representative” Todd Akin concerning “legitimate rape.” Suddenly, Anglophone countries are immersed in discussions about rape.

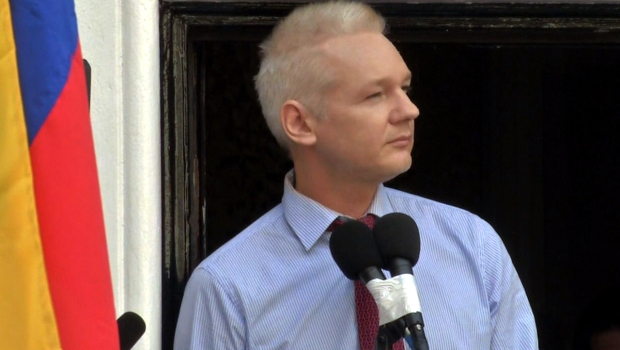

Much of this centers around Julian Assange. George Galloway has made an idiot of himself as usual. However, Seamus Milne in the Guardian argues:

Can anyone seriously believe the dispute would have gone global, or that the British government would have made its asinine threat to suspend the Ecuadorean embassy’s diplomatic status and enter it by force, or that scores of police would have surrounded the building, swarming up and down the fire escape and guarding every window, if it was all about one man wanted for questioning over sex crime allegations in Stockholm?

That’s probably true. But so is this comment by Hadley Freeman in the same paper under the forceful headline “Rape is Rape is Rape”:

Assange is dodging rape accusations from two women. Not Wikileaks. Women. Same first letter. Different things. Also, while you can – contrary to other certain beliefs – become pregnant if you are raped, you cannot become pregnant from Wikileaks. Just to clarify.

When I posted on Assange a couple of days ago, I must admit that I was not fully aware of the details of the allegations against Julian Assange and seeing them discussed in Australian media as sexual harassment, I passed that on without checking, as some commenters pointed out. As the quotes above suggest, there was a gender divide on Assange that I fell into without thinking.

So the one “benefit” of Akin’s ridiculous remarks might be that we can have a broader discussion about violence and legitimation. There is obviously no justification or legitimacy in any act of sexualized violence. Equally, Akin did not “mis-speak” because the radical right believe in the legitimacy of their own violence. It is the counterpart of the violence that seeks to dictate reproductive choice, sexual orientation, marriage equality and so on. But also the violence that ends occupations, breaks strikes, and fires bullets. All are considered legitimate because that is the effect of the force of law.

One reason that I have said that the right to look is an exchange between two that precedes law is precisely this force of law. It has compeled slavery and legitimized violences of all kinds. In the modern era, such violence has often used secrets as a further justification. However, revealing secrets is no more of a justification for violence, if the allegations against Assange are accurate (and we should remember he has not yet been convicted). Nonetheless, we need to remain against heroes.

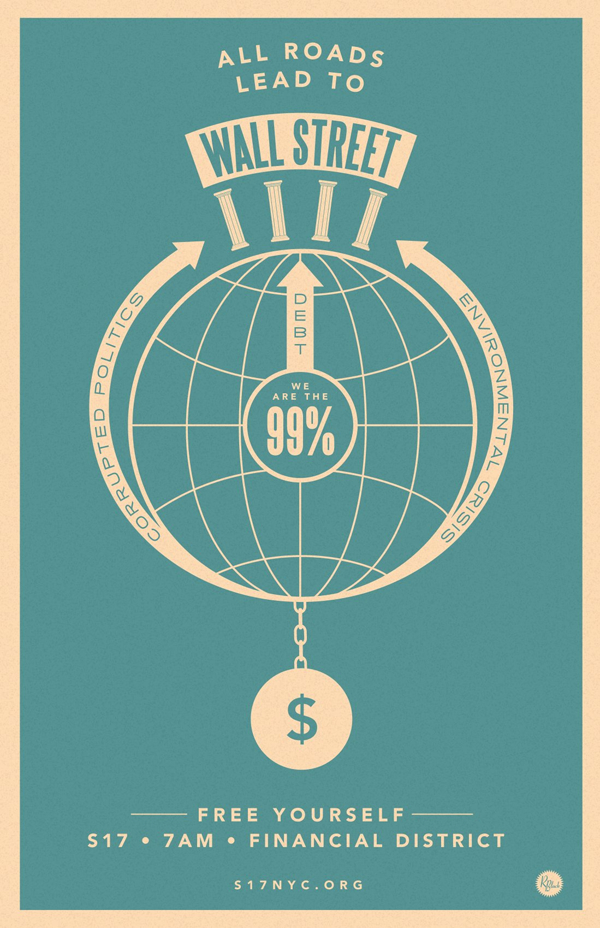

The tactic of consensus within the Occupy movement has been much questioned. It does have the virtue of finding another path to decision making than the 51-49 process that so dominates official politics. It has not prevented (or, to be fair, in any way caused) allegations of sexualized violence within the movement. It does not, however, claim legitimacy, sovereignty or authority and that is at least an important step in the right direction.

This is also a movement of bodies: placing bodies in space and claiming the right to be in our bodies as we choose. It shows how much there is to be done that a person’s right not to have their body used by another person is still the subject of international debate.