This is the first half of the text of my part as The Expert in ‘Yours in Debt!’ minus some parts that won’t make sense here. I’ll expand on some sections of this later. It’s open source, so use it as you will:)

ENTER, CARRIED BY THE ASSISTANTS

Debt. We are all in debt. We are yours in debt. That does not mean that you are in debt to us or we to you. Rather, we live in a society of debt. In this society, the primary means of social connection is not between people but between people and their loans. This society of debt replaces other means of social organization.

Once upon a time, we used to say that there was government of the people, by the people, for the people. In civics class, they called this the public square, the place where debate and public opinion shaped democracy. Last year in this city especially and many others across the United States, we went to the public square and we were evicted. Some of us were arrested. Some were beaten. At this moment, a gentle man named Mark Adams is doing 45 days in Rikers Island. His offense was to set foot on land owned by Trinity Church Wall St. There was a sign saying “Open to the Public.” We are not the public. You are not the public. The public is a means to control and organize us.

More recently, people talked of a consumer society, a society where people were mediated by goods. So a man my age might buy a red sports car but not primarily for transport. A woman might buy some shoes but not really for footwear needs. It was known as the society of the spectacle, dazzling us with the lure of the commodity. The spectacle isn’t very spectacular any more. If you’ve seen The Avengers, you’ll know what I mean. We still buy stuff of course but it wasn’t made here, it doesn’t last very long and has little compelling power.

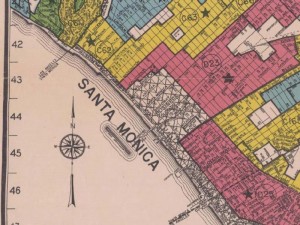

Where we are is in debt. Debt is a space, a social space that has depth and dimension. That’s why we talk of “getting out” of debt more than we do of paying off our debt. Here I want to map that space with you.

The first layer is what I call underground debt. This is where you give money to a friend who needs it. You don’t expect to see it again but you give it anyway. Then when you need money you might go to a pawn shop–that’s P-A-W-N. Here you can get a small amount of money for one of your possessions, which, again, you probably won’t see again.

So prevalent is this culture that there are now not one but two reality TV shows devoted to it. One’s called “Hardcore Pawn” and the other is “Reality Pawn.” Both are playing with the idea that debt is obscene, something to be kept out of sight, except here it is, all too visible. On the other hand, loan sharking and other forms of criminal lending that we all know go on are invisible but palpable.

Above us is what I call Penthouse Debt, playing on the obscenity metaphor. This is where debt gets bought and sold, people make money on it, where banks, financial services, corporations play with and manipulate debt. At the highest point of this level is sovereign debt, the debt of nations, so reliable that it is never entirely paid off but never fails. Until it does. Or threatens to. And then it’s back down here with us.

Where we are, debt is very visible. It identifies, locates and quantifies us. It keeps us in place but fragments our social world. This is what I call the Debt Square of personal credit. So let’s together identify the four corners of the debt square.

[The Expert asks the audience to identify sources of personal credit]

1. Credit cards. There are $800 billion of rotating credit card debt. On average, we are charged 16.24% interest for that debt, while the banks pay about 3.25% to get it. So even before they charge you a membership fee or any of those other fees they like to charge, they’ve made about 500% profit. At the same time we should note that in the present system of finance capitalism, debt is how banks make money. You might assume that if someone makes a deposit in a bank of $100, that’s what they have to lend. In fact, they can lend 3, 5, 10 or even 100 times that. Now we learn that the interest rates they charge us are fixed in the first place. The very notion of a “free market” turns out to be a fantasy.

2. Education Debt. Or student loans. There are $1 trillion in outstanding student loans. I have trouble understanding what a trillion is. It’s a one with twelve zeroes after it. To borrow one trillion dollars over the course of 2012 years, you would have to borrow $1.3 million a day, every day for the whole 2012 years. To put it another way, there are one million people with over $100,000 in student debt. Put them together and you’d have a city the size of Columbus, Ohio, the tenth largest city in the United States. All this appears to be out of control, as no-one can prevent endless tuition increases. The result is that, at the moment where young people’s lives should be beginning, they find themselves with the equivalent of a mortgage for 120 credit hours. This is insane.

3. Mortgage debt. This is the largest sector of all. There are about $13 trillion of personal mortgage debt, which, not coincidentally is roughly equivalent to the annual gross domestic product of the United States. For as long as we can remember, we have been told that to buy a house is to guarantee personal wealth and prosperity, as well as bringing related benefits to the nation. Now fully one-third of those mortgages are under water, meaning that the loan is more than the home is worth. We feel less wealthy because we are. In fact, median US net wealth has declined a stunning 40% between 2007 and 2010 to $77, 300 wiping out the gains of the past 18 years. In Iceland, the government forgave housing debt over 110% of the current value of the home, erasing $1.6 billion of debt. Scaled to the US, that would be about $1.5 trillion, the kind of stimulus that might finally move the economy.

4. Medical debt. This is the hardest area to get precise data about because insurance companies don’t want you to know. What we do know is that of those people who went bankrupt in 2010, 64% cited medical debt as part of the reason for their bankruptcy. You might be thinking that the Affordable Health Care Act, recently upheld by the Supreme Court, will take care of that. Unfortunately, it turns out that 61% of those who go bankrupt with medical debt have insurance. If you’ve ever been sick, you’ll know why. Your doctor may suggest a drug but your insurance doesn’t cover it. The doctor you need to see doesn’t take your insurance. You need a procedure but it’s not approved by your insurance adjuster. In these situations, people face a terrible choice. You may have to decide whether to pay for preventive tests out of pocket. We see people dying unnecessarily all the time for not having tests like colonoscopies. In recent days, the media reported a man who committed suicide after receiving a diagnosis of a terminal disease for which he did not have coverage. He did not want to inflict two losses on his family: his own death and the resulting medical debt. No human being should have to make a choice like that.

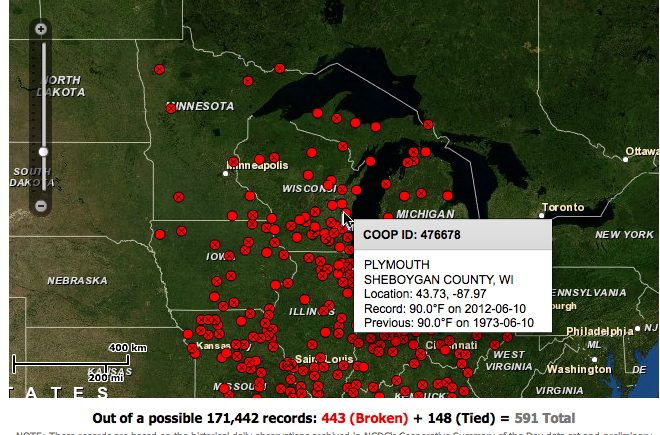

These are, then, the component parts of the Debt Square. At the same time, as we look around it, on all sides there’s something else going on, something that the media do not report. There are many people at all corners of the debt square either choosing to or being compelled to give up repaying their debt. There have been some 5 million foreclosures of homes already. There are another 5 million homes in some state of the foreclosure process. That’s about 40 million people who have chosen or been compelled to give up repayment. In the student loans corner, we have 27% of those owing who are out of deferment now in some stage of default. All across New York I meet young people who have just graduated into unemployment and have decided to go directly into default. The credit card companies have had to write off 10% of all debt in recent years. Again, medical debt is the dark horse, except that we know that people can’t afford their bills.

The question is what we call that. In the eyes of the police, the response is as always “move on, there’s nothing to see here.” In other words, all these tens of millions of people are simply in the wrong with nothing else in common. What if we called what all those people are doing debt refusal? What if we even called it a debt strike? We’d need to recognize that in the legal nightmare of the US, almost all strikes are wildcat strikes, meaning that they are not formally declared. Again, they are the product of desperate necessity as much as carefully calibrated rational choice. That doesn’t make them any the less strikes.

What we are reminded here is that politics is precisely the relationship between what is visible and what is sayable. In 1990, to call someone “queer” was a direct insult. Then Queer Nation stood up and said “We’re here, we’re queer, get used to it.” Twenty-odd years later, we mostly have got used to it and a good thing too. So what seems almost extreme at one moment passes for common sense not long after.

Tonight we want to get a sense from you of what words you associate with debt. I’m going to throw out some questions about debt and the Assistants will write them on the walls to form a word-cloud. In this way we may be able to get a sense of what the meanings of debt currently are for us here tonight.

Questions: how much are you in debt? How did you get in debt? How does being in debt make you feel? What would you like to do about it?

[The Assistants take over. Part II of the text tomorrow}

Like this:

Like Loading...

![yrs in debt 2]](http://www.nicholasmirzoeff.com/O2012/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/yrs-in-debt-2.jpg)