New York is a very parochial city. You tend to stay where you feel comfortable and move in a set of familiar patterns. Today I was out of my comfort zone all over the West side, observing a new corporate district emerging and engaging in some rehearsals for a performance at the end of the week.

Today began with a walk back down the High Line from 30th Street, where I left my car to be fixed with a great group of guys from Côte d’Ivoire. They got a huge kick out of the fact that I speak French, which is apparently not common in their usual clientele of South Asian taxi drivers and New York City officials. It was a place that I fetched up at because of Yelp! As is not uncommon in global cities of the South, this shop actually fixes things, albeit in an improvised fashion. I usually feel wildly out of place in US car places, where it is really obvious I don’t do mainstream masculinity at all well. Here was fine, we talked about the European soccer championships and made fun of people in French.

The casual improvised feel could not be more removed from the High Line. It has extended Chelsea’s art district north and allows for walkers to see works displayed in non-traditional spaces. So there was a large portrait by JR, the French art-ivist, as he calls himself on the back wall of a house. Usually I love JR’s stuff but one piece by itself seemed out of place, just another commercial display. Even early in the morning, the High Line crawls with people, mostly tourists, all taking extensive photographs.

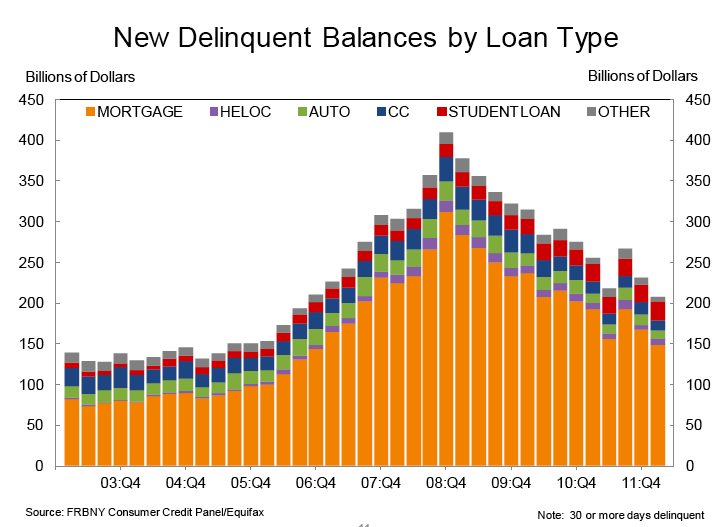

At the north end, there’s a massive building project going on over the West Side railyards. Two full city blocks are being converted into the usual mix of offices, high-end apartments and retail outlets with one or two affordable places in undesirable locations thrown in as a sop. One site is being developed by our old friends Brookfield Properties. This site, which they are calling Manhattan West was announced on September 2, 2011, just two weeks before OWS moved into Zuccotti Park. It stretches from 31st to 33rd Streets and from 9th to Dyer Avenue. It’s huge. When you see the scale of all this, it’s amazing to think that Occupy has had any impact at all.

From there I had to go up to Columbia University to rehearse for what is being billed as a performative lecture on debt in the series Debt! hosted by undergroundzeronyc, a theater festival. The project brings together directors from Eastern Europe, with performers and lecturers from New York. Our project, “Yours In Debt!“, is being co-ordinated by Ida Daniel, from Bulgaria, whose work, so far as I have seen it, seems very much influenced by Brecht and behind him Kafka. The performance we’re doing has an Expert and Assistants, and the latter were very important characters in Kafka.

Just as in Kafka, the Assistants are really in charge of the performance, not because of the way it is structured, so much as because they really are performers. Working on exits and entrances, thinking about cues and so on, you realize how glib the academic use of performative often can be. Applied to ourselves, it means that we do what we do anyway but now with a sexier name. Actually performing feels much harder, even though the topic is one with which I am now only too familiar.

Or is it just rehearsing, trying to work out how to work with people in a space whose dynamics are new? Put like that, it starts to seem more familiar. There is a curious dynamic here by which I began writing about the performativity of Occupy and now I am doing a performance about Occupy. This is what happens if you venture onto the West Side.