Today for only the eighth time in the era of the telescope, Venus made a transit across the Sun that was visible from earth. This transit is, as all those since the eighteenth century have been, a “transit of empire,” to quote Jodi Byrd. For much of that time, empire has been in the ascendant. Perhaps, if we might indulge in the pathetic fallacy, today’s transit might herald the exit of empire.

Today for only the eighth time in the era of the telescope, Venus made a transit across the Sun that was visible from earth. This transit is, as all those since the eighteenth century have been, a “transit of empire,” to quote Jodi Byrd. For much of that time, empire has been in the ascendant. Perhaps, if we might indulge in the pathetic fallacy, today’s transit might herald the exit of empire.

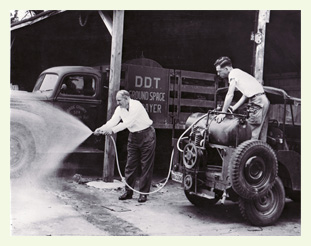

The pathetic fallacy–the idea that the natural world reflects human moods–was itself the product of industrial modernity. Our own pathetic fallacy is both that humans can ignore the destruction of the natural world caused by fossil-fuel industry and that there is a modern “we,” who are not and have never been indigenous.

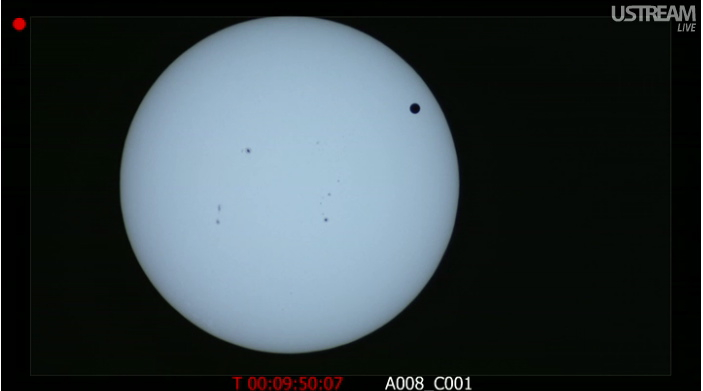

It had been mostly cloudy today in Manhattan but when the sun came out at 5.45, I left the gym and jogged up to Union Square to join perhaps the geekiest crowd ever seen outside. About a hundred astronomy nerds and passers-by clustered around some grad students with specially-rigged up telescopes to allow looking at the sun. At six o’clock, the clouds were thick overhead

At that point, and I am not making this up, the NYPD sent two white-shirt officers and five uniforms to investigate the crowd. Perhaps, I thought, Bloomberg has now decreed that the sun revolves around him and so this event was heretical. Luckily, they decided against the use of force and the clouds did thin for an instant. The carefully masked telescopes allowed us to briefly see the image of the sun with the tiny dot of Venus on a thick screen placed where you would normally view the image.

It was not the kind of high-resolution image we have become used to, such as this from NASA, who are live-streaming the event.

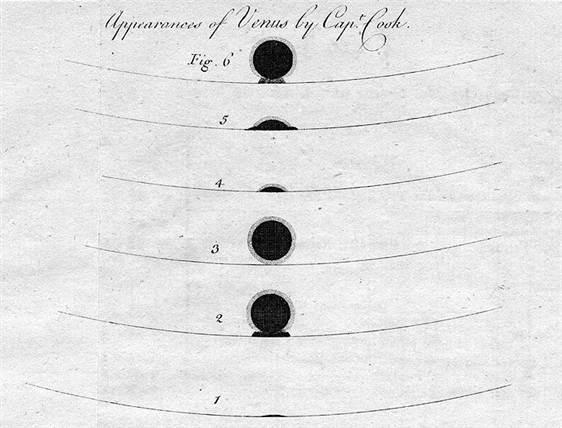

It’s noticeable that their telescope is based in Hawai’i, an American colony, creating an echo with the first measured transit of Venus in 1769, observed from Tahiti by Lieutenant (later Captain) James Cook and the crew of the Endeavor. This voyage is one of the most minutely analyzed events in colonial history, thanks to the immense data assembled by the British crew, ranging from Cook’s own journals to the drawings of Joseph Banks and the paintings of William Hodges.

In more recent years, the emphasis has rightly shifted to locating the “voice” and presence of the indigenous peoples, whose pre-contact culture can be deduced in part from these materials. This encounter inaugurated what Jodi Byrd, a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma and professor at U. Illinois Urbana-Champaign, has called:

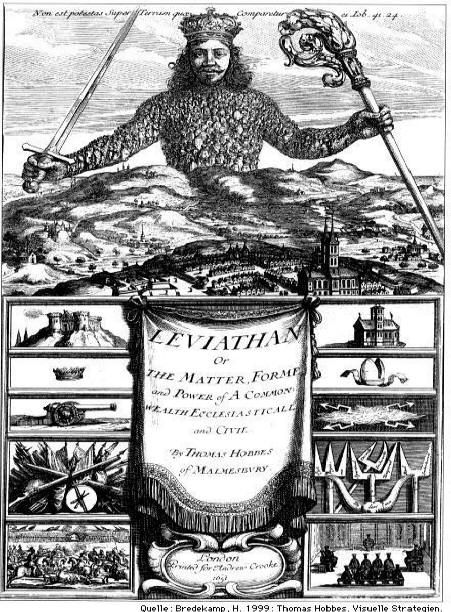

the imperial planetarity that sparked scientific rationalism and inspired humanist articulations of freedom, sovereignty, and equality [which] touched four continents and a sea of islands in order to cohere itself.

While many of these terms were and are valued by many, this history is also one of the violent dispossession, compulsory religious conversion and eradication of indigenous cultures. For Byrd, therefore, “transit” has a double meaning, suggesting

the multiple subjectivities and subjugations put into motion and made to move through notions of injury, grievance and grievability.

What’s noticeable here is that “movement,” like our own Occupy movement, is not singular but contradictory.

Reflecting on the U.S. context, Byrd points out that one of the “grievances” in the Declaration of Independence was the British use of

merciless Indian savages.

That image persists to the present via the cowboy movie, even so-called classics like The Searchers (1956), and mediocre animated cartoons. Witness the present furore over Elizabeth Warren’s claiming of American Indian descent in the Massachusetts Senate campaign. Never mind that everyone who has ever run for anything in Massachusetts, let alone the US as a whole, always claims Irish descent on the most tenuous basis. Claiming to be Indian is somehow always wrong.

The language resists here. No one is born indigenous, they are made indigenous by the arrival of the colonizer. Indian is a misnomer, but so is Native American. The notion of the Fourth World, composed of indigenous peoples, simply raises the question as to why they are not the First World as indigeneity, if it means anything, must mean being there first.

A transit passes from one side of that which it encounters to the other. Its end its always part of its journey. The damage will have been done.