Debt is prison. Few debtors, whether dealing with students loans, credit cards or mortgages, would disagree I imagine. By this phrase I intend not a metaphor but a description: debt is a systemic way to limit options, impose unfreedom and sustain the unfree labor market on which capitalism depends. In the United States, this debt-prison system is necessarily intertwined with what Angela Y. Davis calls the post-slavery prison-industrial complex. Resisting debt servitude in this country is a central part of extending and completing the Civil Rights movement.

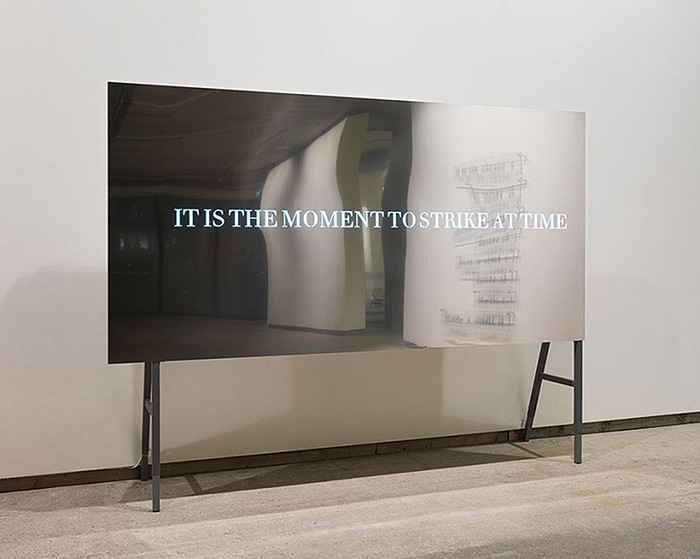

The old face of the new refusal

This is a proper concern for Occupy for any number of reasons. As I mentioned a while ago, Wall Street was the site of New York’s slave market. Combine that with its role as a barrier against the indigenous population (hence the name) and as a site of financial speculation and we begin to understand what the symbol “Wall Street” really means. So while what I have to say here may sound like a history lesson, it’s very much a history of the present that enables us to see what how high the stakes are in the apparently technical problem of student debt.

Transatlantic slavery was a system dependent on debt financing. The slavers borrowed money for the costs of the voyage and the trade good they exchanged for human property in Africa. These goods were far from worthless and developed into a money form based on copper. The enslaved were purchased by American planters buying on credit. It was only with the sale of the products of the plantation back in Europe that true profit entered the system.

But this profit was spectacular: a ship called the Lively left Liverpool, England, in 1737 with cargo worth £1307 and returned with £3080 in cash plus a cargo of sugar and cotton. In short, a profit of at least 500%, unavailable anywhere else in the early modern financial system. Don’t take my word for it: here’s Adam Smith, inventor of the concept of the market in his 1776 Wealth of Nations: “The profits of a sugar plantation in any of our West Indian colonies are generally much greater than those of any other cultivation that is known.” Haiti was the wealthiest place on the planet when its revolution began in 1791.

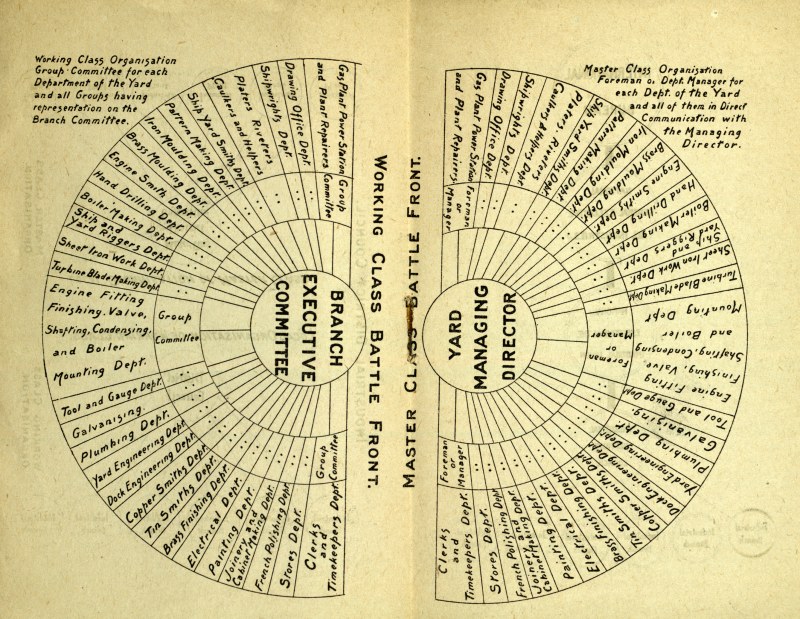

Just as the factory system described by Marx was not participated in by anything like a majority of workers but was typical of its time, the slave system was the hallmark of American capitalism. Today I would argue it’s the debt-prison system that marks out the peculiarity of the United States. Debt servitude, racialized segregation and mass incarceration of those so racialized are thus the true American exceptionalism–while debt is central to capitalism worldwide only in the United States do we have such a peculiar and networked system of debt as racialized punishment.

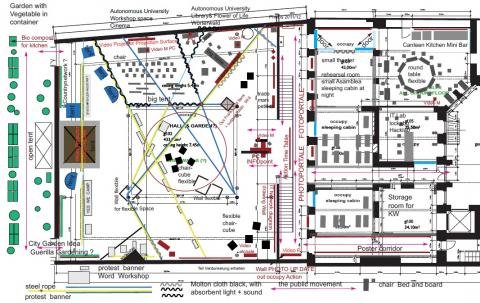

US slavery persisted much longer than in Europe, as we all know. At the outbreak of the Civil War, the enslaved enacted a general strike against slavery in which half a million people moved away from plantations to the North. The South claimed that millions of its capital were, so to speak, contained and hence “lost” in the bodies of the enslaved in 1863. The period known as Reconstruction (1865-77) was a struggle by the formerly enslaved to escape being, as it were, recouped by the planters into the debt-prison system. In so doing, the freed used many of the tactics we continue to deploy today from occupying to marches and strikes. It failed because of a Wall Street real-estate speculation crash that produced the typical binary form of US racism in its wake.

The freed claimed their own land to farm. If the Freedmen’s Bureau would not give it to them, they occupied it. The concept was simple: a small group of people would create sufficient food for themselves and a surplus to trade with. It was a sustainable anti-poverty system that did not rely on wage labor. But as David Graeber puts it:

It is the secret scandal of capitalism that at no point has it been organized primarily around free labor.

The idea that the freed would work freely was abhorrent to the planters and to Northern capital alike. Instead, they were to be compelled to work for their former owners.

All the new labor systems that were developed to this end were, as Angela Davis puts it, “dramatic evidence of the persistence of slavery.” That is to say, share cropping, tenant farming, the scrip system and the convict lease system of imprisoned labor all depended on a new series of connections between debt, labor and prison. Share cropping meant that the farmers were entitled to a share of the crop they produced, usually a third. However, as this meant they were paid only once a year, they had to make purchases on credit for the rest of year at the notorious crossroads or company stores. Very often the annual payment would not cover this debt meaning that the sharecropper could never escape the land. In fact, wage laborers were often not paid in cash but in scrip, a paper form allowing you to buy things at inflated prices in the company store.

Even this labor was too expensive for the planters. So the new Black Codes passed in the South after the Civil War criminalized minor financial transgressions. In Mississippi any person who “handled money carelessly” could be declared a vagrant and imprisoned. Simple theft, whether of bread or an animal, was turned into a felony and those convicted were imprisoned. The new African American prisoners were turned into a virtually free labor force by the convict lease system in which employers could use convicts to work for almost nothing. Even today, the University of California gets its office furniture from prison workshops.

The freed resisted these innovations. In South Carolina, the legislature attempted to borrow money to buy land for the freed. Wall Street would not buy their bonds. The laborers organized and called strikes for waged field labor. In Louisiana, workers refused to labor for their former owners, organized and marched. One freed organizer named John J. Moore testified that planters said to them: “if you do not let politics alone you will get killed here.”

But in 1873, Wall Street crashed, having speculated wildly in railroads and real estate. It took down the Freedmen’s Bank and with it about $3 million of deposits made by the formerly enslaved. Emboldened by the crash, known then as the Great Depression, planters reduced wages where they were paid, as in Louisiana, from $18 plus food to $13 only a month. When the Hayes-Tilden compromise withdrew Federal troops from the South, the political gains of Reconstruction were rapidly overturned and the convict lease labor system swung into full effect.

Even now, the freed were not willing to give up. In 1887, a major strike on the sugar plantations of Louisiana was repressed only by armed force, in which about thirty strikers were killed and hundreds injured. Although the strikers came from all backgrounds, the planters defined them as “black” and themselves as “white.” It was three years later that the “Separate Car Act” enforced racialized segregation on trains in Louisiana, leading to the infamous 1896 Plessey v. Ferguson case at the Supreme Court that declared “separate but equal” facilities to be legal.

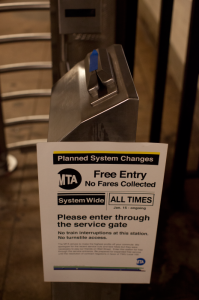

In short, the debt crisis that has generated over one trillion dollars of student debt, $700 billion in credit card debt, 4 million foreclosed homes, 6 million other homes in danger of foreclosure is part and parcel of the system that has placed over two million people in jail.

The consequence is simple and challenging: there will be no making the debt system better, or less burdensome. Even today, sub-prime lending was reported to be on the rise again. Graduate student loans accrue interest immediately as of next year so that someone working on a PhD will have eight years of interest at a minimum of 6.8% by the time they graduate. Debt is so central to what we are trying to occupy when we Occupy Wall Street that it cannot be separated out.

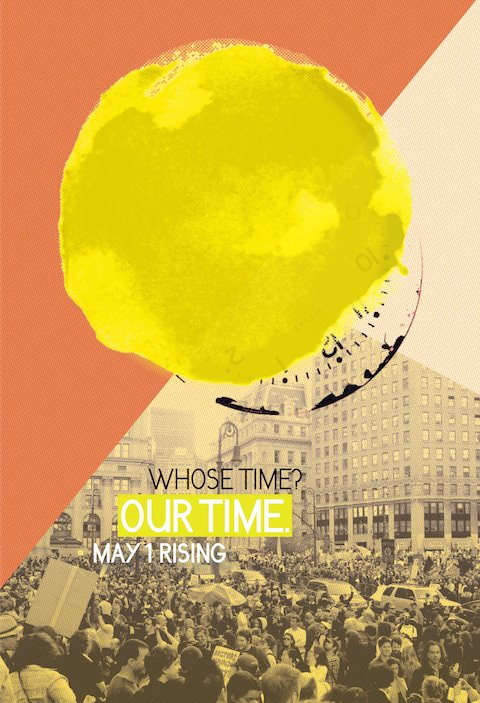

I do not think this is depressing but rather it shows that Occupy continues to advance our understanding of the tasks that lie before us. It should be remembered that it was once said to be impossible to abolish slavery, and not long ago it was supposed to be inevitable that there would always be segregation. It’s not inevitable that we agree to live in debt, accept debt as our punishment for not having been born wealthy and apply for opportunities to get more and more in debt. The first step is refusal, which is why the new slogan going the rounds is Bartleby’s rejoinder to a Wall Street banker:

I would prefer not to.

Me too.

Like this:

Like Loading...