Why is tonight different from all other nights?–and all other Passover nights? Because tonight we don’t say “next year in Jerusalem.” We say “next year in Cairo.” Tonight we do not think about Occupy but about the ongoing colonial occupations around the world that continue to oppress. And tonight we hope for another future.

In the traditional Passover service, the gathering say “Next year in Jerusalem,” the utopian wish of the diaspora. The “Jerusalem” of the Haggadah (the text used during the service) was interpreted by many modern progressives in the manner of Blake as a place without slavery, the place of emancipation.

Often, such affinities are felt to have been expressed by the work done by Jews during the U. S. Civil Rights Movement.

The Sarajevo Haggadah, noted for its beautiful illustrations was the exemplar of how the book could also mobilize cross-cultural alliances. It was hidden and protected from the Nazis during World War II by local people, including a Muslim cleric. Later it was again saved from damage during the devastating “ethnic” civil war in the former Yugoslavia.

These affirmative histories feel remote from modern Jerusalem as it is ruled under what is, to use Jimmy Carter’s telling phrase, a “new apartheid.” In Jerusalem, Orthodox Jewish men actually send Jewish women to the back of the bus, as if to say that they want to erase the Civil Rights history.

So today the anti-slavery “Jerusalem” is somewhere much more like Cairo after the Tahrir revolution than it is the city of that name.

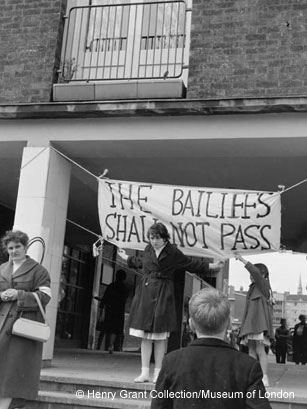

Perhaps no visual example is more telling than this picture:

It shows the city of Bethlehem, named as the birthplace of Jesus, a city of importance for Jews as the seat of King David and long part of the Arab Caliphate. Now it is divided by the separation wall that epitomizes the key tactic of global counterinsurgency: once you have identified your insurgent, separate them from the “good” population.

There’s so much writing about the disastrous consequences of Israeli policies, above all from progressive Israelis like Ariella Azoulay, Eyal Weizman and Adi Ophir, that there’s perhaps no need to dwell on them. Except that it has now become clear that Israel has embarked on a “necropolitics,” a sovereign determining of who it is that must die, which now extends to other nations. The entirely unsurprising “October surprise” of the 2012 election will be the Israeli attack on Iran, telegraphed and planned by Benjamin Netanyahu, whose contempt for Obama might be enough to get him on the Supreme Court. Just because we can see this coming does not mean it will not have most serious consequences.

Not least will be a renewed clampdown on all anti-militaristic, anti-hierarchical politics. It should be remembered that the tent city in Tel Aviv was evicted long before Liberty Plaza. Only you can’t call it the Israeli Occupy because that already exists.

Looking back, as one does on ceremonial days, I reflect on the opportunity that the Oslo Accords appeared to present in 1993. Among them was the possibility for a secular Jewish identity that was not linked to Israel and also not shamed by it. At the time, the late lamented Edward Said indicated that Oslo was going to be a disaster. Along with many others, I could see that but hoped that it would lead to something better. It did not and the possibility to play with being “Jewish” disappeared as well. Israeli officials do so much in the name of “Jewish” and not just Judaism that it would be sophistry to do otherwise.

Nonetheless, there is of course a new Haggadah this year, translated and commented upon by earnest, bearded young men from Brooklyn of the Jonathan Safran Foer kind. Actually, it is edited by Foer.

The Haggadah says that

in every generation, a person is obligated to view himself as if he were the one who went out of Egypt

I don’t want to do that now. I want to stay in the “Egypt” that we’ve seen since 2011, the Egypt of Tahrir. I want to decolonize Palestine and finally bring an end to slavery. L’chaim.