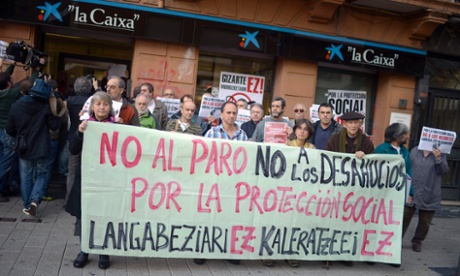

The old adage says you can’t go home again. Like most such remarks, it’s about half true. I spent a lot of my twenties in the British left-wing world, at the kind of event I was at today. It was called Up The Anti, a discussion of where to go next after Occupy and all that.

The old patterns were very much in evidence: a plethora of small parties and groups claiming allegiance to Trotsky and other revolutionary legacies; a very serious focus on the issues; some under-representation of women and people of color on panels; unco-operatively designed rooms with steep rakes and fixed desks.

And despite all that being true today, the panel organized by the Occupied Times and Strike Debt UK had a familiar energized feel of the beginning of a movement. We began with David Graeber doing his usual, excellent introduction to debt as a political and historical topic. He has a great knack of making you feel smart as you listen to him and he won the audience over to the idea of debt as an activist issue.

I went next and had the simple pleasure of describing all that Strike Debt has been up to from the first debt assemblies via the Debt Resistors’ Operations Manual and the direct action days to the Rolling Jubilee. I gave it a lot of “jubilant” energy, plussing it up as we say. So when I announced that the fund has raised enough money to abolish $10 million in debt (ok, almost), I was surprised to be interrupted by applause, very un-English.

I think I benefited from not reading as English to the audience, at least in the sense that I don’t have a place in the complex intra-left debates. I don’t carry any of the baggage of Occupy London, which several people suggested had left some difficult legacies, although I don’t myself know directly about that. And the Jubilee is just a win, and we all need wins from time to time.

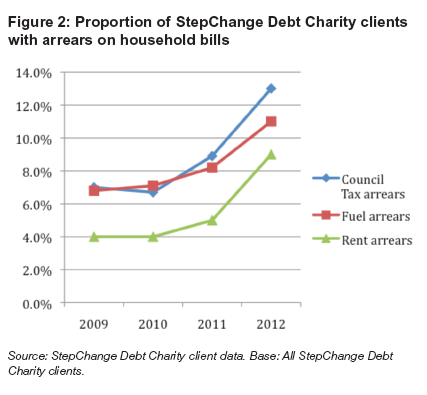

There was a great presentation that followed about Third World debt and we went into breakouts. The direct action breakout that I joined was clearly interested in doing a Jubilee in the UK, although some people pointed out differences in the credit laws that make it much more difficult. There were other good ideas about working with community groups, looking ahead to housing benefit cuts and so on. It was all a bit vague and suggested the need for a lot of research.

It was all so familiar from only six months ago, when we decided to do something similar in New York. If people keep coming, talking, researching and doing actions, Strike Debt UK will find its own way to engage the debt system. I got a contact buzz off the activists. It seems that to go home, you have to go differently than when you were first there. Then it works.