Unless we can control the space we occupy, we will not be able to really love one another

Kalamu Ya Salaam

I came across this sentiment from New Orleans poet and activist Kalamu Ya Salaam in thinking about how we might start to feel in our bodies the extinction that is going on. Many folks feel that a genocide is going on in New Orleans. It’s actually going on across the planet. Abolition or extinction. That’s the choice.

What did we learn from Hurricane Katrina? In the words of activist Clyde Woods:

Katrina revealed the present and future costs of a fragmented, de-linked, privatized, and devolved state; no one is in charge.

From levee failures to the destruction of public housing and the manufacture of homelessness, post-Katrina New Orleans demonstrated the predatory nature of modern capitalism.

It’s easy to see those forces at work again in post-Sandy New York. It’s tempting to see this as a feature of disaster recovery. It’s better understood as the becoming visible of the planet of islands. These islands extend from Manhattan to Maui in the literal sense and are the most at risk. But whereas John Donne said,

no man is an island,

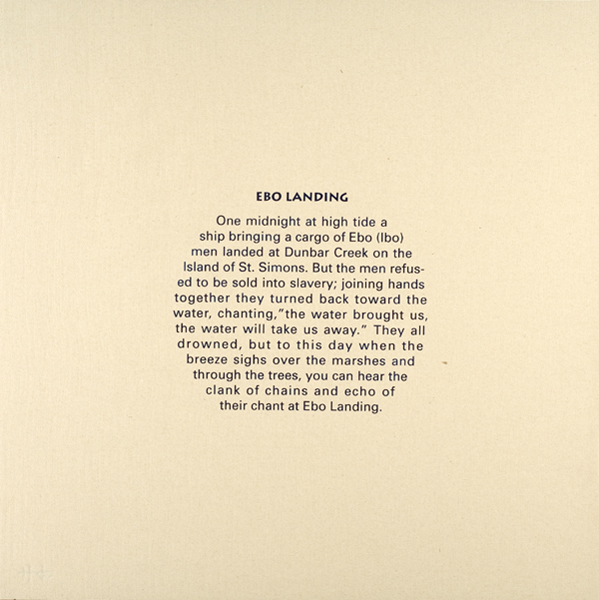

neo-liberalism says to us: “you are all islands.” It wants to sever all cultural ties, all traces of community and leave us exposed to the winds of the market and the rising sea of global inequality. Some will literally drown, others drown in debt, all lose their sense of identity.

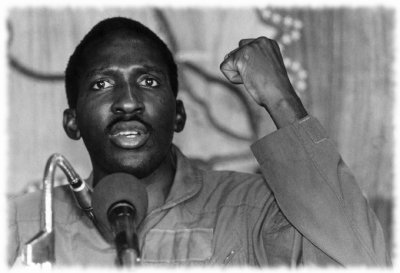

This is Manny.

He’s a seventh-generation master navigator now living on the island of Guam in the Central Pacific, a US military colony. He’s seen here at the canoe house built by the Traditions About Seafaring Islands group, one of the actions taken by the indigenous Chamorro people to claim their long-ignored rights.[i]

They have revived traditional navigation in which canoes built by hand, using no modern materials, are sailed thousands of miles by navigators relying on their knowledge of the stars, the ocean and its interrelation with land. A man of few words, Manny explains his skill with an aura of authority. I ask him if he has seen any difference as a result of climate change.

He notes that he has always been able to predict the weather. His colleague Larry Cunningham interrupts to give substance. Once the group were planning a voyage of about 1500 miles. Manny simply said that they needed to be back by the end of the first week in July. On July 8 that year a typhoon struck. In this equatorial region, weather patterns observed over generations have been sufficiently stable to allow for such precision, he explains. Manny looks at me. “Now I can’t tell what the weather will be.”

The cultural studies scholar and activist George Lipsitz writes:

The South is not a periphery of the US racial order; it is its center.

That insight can be made planetary. The global South is not the periphery of racialized neo-liberalism, it is its center. This neo-liberalism produces whiteness as unmarked Anglophone commodity capitalism. It ignores the fact that over a third of the spoken languages on the planet, even today, are indigenous to the Pacific “sea of islands.” We are losing our cultural gene pool, just as surely as we are losing our right to existence.

Here’s Kamalu Ya Salaam again:

white people

come in all colors

their systems sink

past skin

anchoring into bone, mind

flesh, heart and soul

it is geno-suicide

to minstrel aliens

but some of us do die

strangled by our own

hands

[i] My thanks to Keith Chamorro, LisaLinda Natividad, former Senator Hope Christobal, Lawrence J. Cunningham, the University of Guam and many others for kind assistance during my stay on Guam in August 2010.