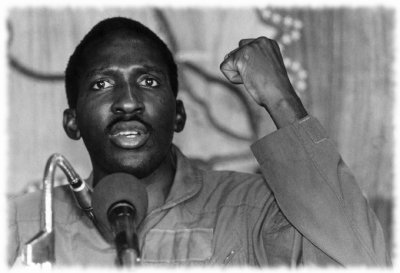

Today is the 25th anniversary of the murder of Thomas Sankara, president of Burkina Faso. His killing came a few months after he had called for African nations to go on debt strike against multinational lenders. That’s not a coincidence. So as part of the global week of action on debt, the Spanish 15M movement has called on us to remember Sankara’s message today. Of course, the best legacy we could offer would be to accomplish debt abolition.

So, first, hit the link and get Fela Kuti’s amazing tribute to Sankara playing in the background. Now let’s review the basics. The 15 M statement reads:

Thomas Sankara was president of Burkina Faso between 1983 and 1987. Sankara, a soldier, came to power via a coup, but unlike other presidents whocame to power by the same means, he always prioritised the welfare of the people of Burkina Faso. He nationalized land and distributed it among the peasants, nationalized minerals, launched immunization and literacy campaigns, banned genital mutilation and defended by all means equal rights for women… and confronted the dictatorship of debt.

This is what he said at the Conference of African Unity in 1987:

The debt cannot be repaid, first because if we don’t repay, lenders will not die. That is for sure. But if we repay, we are going to die. That is also for sure. Those who led us to indebting ourselves had gambled as if in a casino. As long as they had gains, there was no debate. But now that they suffer losses, they demand repayment. And we talk about crisis. No,…, they played, they lost — that’s the rule of the game, and life goes on.

Now we might wish that we had a President who talked in this fashion. Sankara’s analysis saw debt as a continuation of colonialism into a new form:

Those who lend us money are those who had colonized us before…Debt is neo-colonialism in which the colonizers have transformed themselves into a form of technical assistant….Debt is a cleverly managed reconquest of Africa.

Sankara went so far as to call this form of debt a “financial slavery.” Since Strike Debt and the other debt resistance movements have gained attention, there have been those who have wanted to criticize them for making this analysis. The critics take upon themselves the name of the (neo)colonized but ignore this African legacy.

Such internal squabbles are irrelevant. The important point is this. Just as the Haitian Revolution drove the French Revolution into its radical phase; just as the Algerian and Vietnamese revolutions produced the Euro-American wave of 1968; so now the debt abolition movement is implementing decolonial politics in the metropole. In short: throughout the colonial era (since 1492), there have been successive waves of radicalism, from the colony to the imperial “center.” This is not surprising because it is in the colony that imperial power is practiced and exercised.

The “neo” in neo-liberalism thus comes from using such colonial techniques in the regions of that “center” that are now deemed dispensable. After the financialization wave swept through the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries in the 1970s and 80s, the banks turned their attention to Heavily Indebted Poor People in the late 90s and 2000s. With the crash of that tactic in 2008, extraction is now concentrated on those regions of Europe that were considered “Oriental” in the nineteenth century (Greece, Southern Italy, Spain and Portugal), as well as people of color in the United States.

And as Sankara said, it seems that

the crisis gets worse each time that the popular masses get more and more conscious of their rights against exploiters.

So Sankara proposed that, against the G7 (as it was then) and the Club of Rome, African nations should form their own “club,” a united front against debt. He stressed that European and African masses were not antagonistic but were rather being exploited by the same people. Unity was essential, he noted, adding that if Burkina Faso was the only nation not to pay, he would not be there for the next conference. As indeed he was not.

The final message in Sankara’s speech was the necessity of African mutual aid. Rather than exporting raw materials to the developed world and importing finished goods, Sankara called for an internal African market. Such a market would still be huge but it would allow for disarmament and development. This point is crucial: debt abolition was not, in Sankara’s terms, a “provocation” but a crucial first step towards a sustainable regional economy that was not centered on war.

It has not happened. Yet. Perhaps the wave of refusal spreading across South Africa against these same, unchanged conditions will become Sankara’s legacy. Let’s do what we can to make it happen.