The second remarkable video I saw yesterday in Liverpool, after Unfinished Conversation, was not so celebrated by the Biennial. I had to find it at the end of a dark corridor in the Cunard Building. Unlike the large space in Bluecoat where Unfinished Conversation was showing, there were three chairs available to watch Marat/Sade, Bohnice directed by Althea Thauberger.

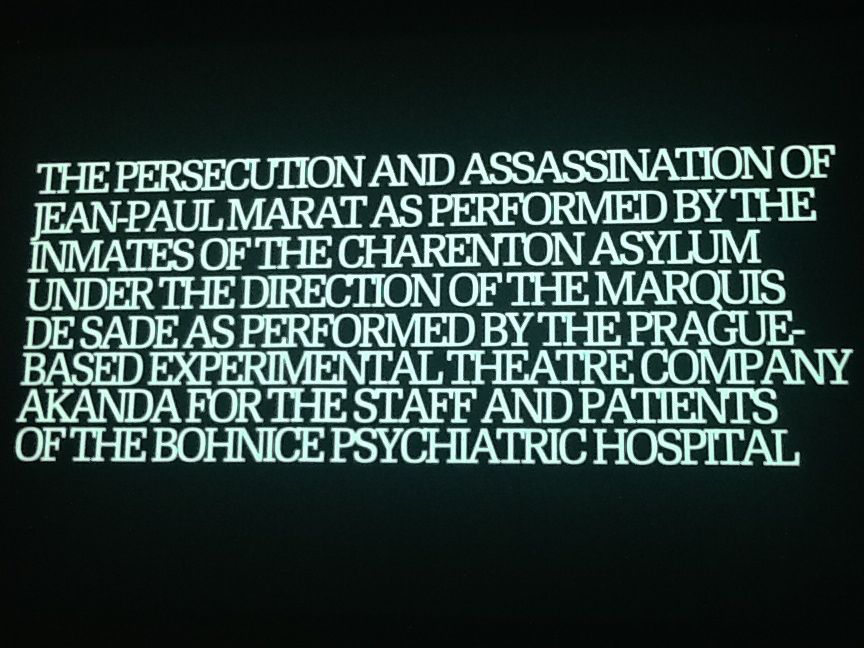

As you can see above, it depicted a restaging of Peter Weiss’ 1963 classic play Marat/Sade in an actual asylum in Prague, now capital of the Czech Republic. Weiss’s play reflects on the costs of revolution, the tension between the imagination (represented by the Marquis de Sade) and the needs of the impoverished for rapid change (represented by Jean-Paul Marat). Weiss set his play in the new (as in new in 1791) lunatic asylum of Charenton. The restaging in Bohnice physically resembled it but was an active institution and the audience (shown below) were Czech psychiatric patients.

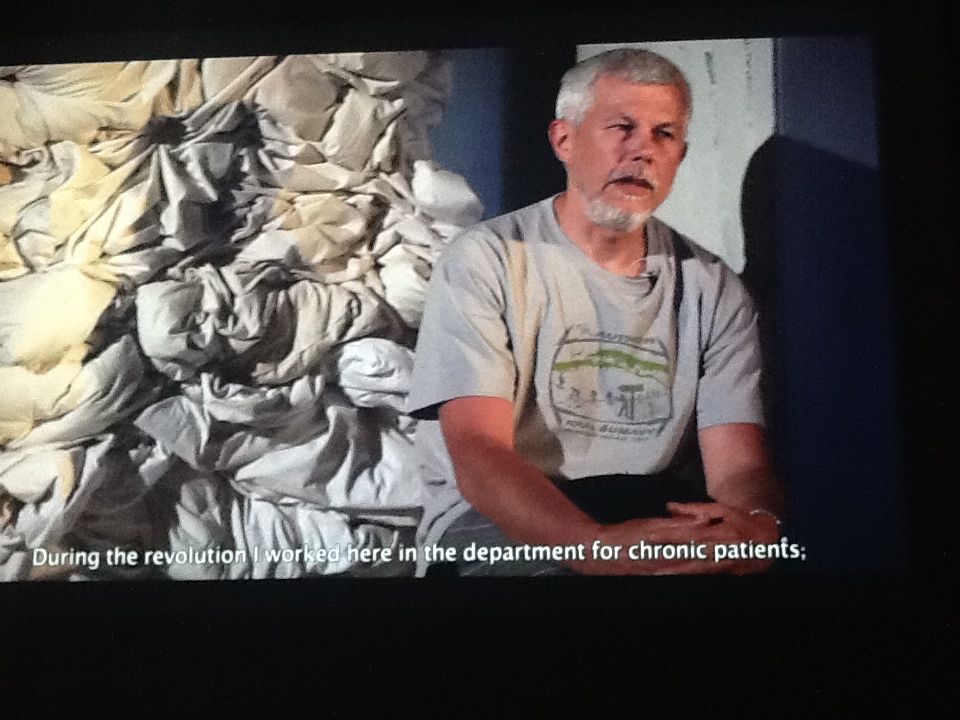

The context of the performance was the perceived failure of the “Velvet Revolution,” by which the-then Czechoslovakia overturned Soviet-style Communism in 1989. Video of the drama was intercut with interviews with the director of the institution, residents and staff.

The director and some staff had had high hopes in 1989 that now they would be able to create a model, modern institution. Now they had debated whether to even accept the play because it might mitigate the sense of failure around the hospital. As Weiss’s highly stylized play unfolded, we learned that Bohnice houses some highly unusual treatments. It has a program in existential psychiatry, centered on the inevitability of death that seems almost parodically Central European.

It also has an active program in sexology. On the one hand, this seems geared towards an understanding of the workings of desire. On the other, they literally castrate people. With their consent, so they say. Another speaker dryly described how he was part of the EU investigation into whether the hospital was committing acts of torture, including the very act of preventive detention.

One of the staff described his involvement with the 1989 revolution as a form of delusion. Clearly, he had hoped for so much more.

This bitterness was enhanced by a discussion with a translator who had worked for Havel, Reagan and Mrs Thatcher and was now a patient. His sardonic cynicism seemed very familiar and anything but insane.

Most notably, a woman called Sarka Kapkova, also an inmate, provided a searing critique of the disciplinary apparatus and the pharmacological regime that could have been by a well-versed anti-psychiatry graduate student. She also ventured that it was the post-Soviet “freedom” that had first caused what she nonetheless described as her “illness.” That is to say, the free market had driven her into an insane asylum.

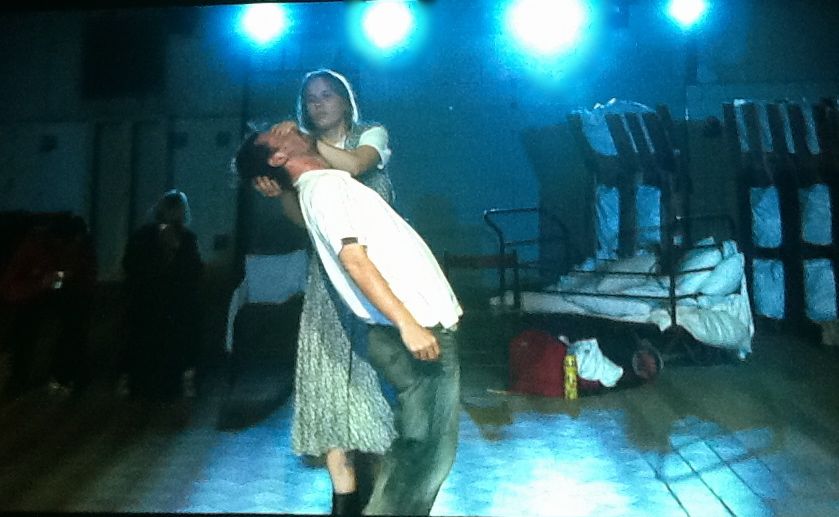

So across this film echo the accumulated discontents of 1789, 1968, 1989 and the present with a seasoning of Kafka to allude to the horrendous mid-twentieth century in Europe. The audience for the play, as presented, watched quietly for the most part. They enjoyed the rendition of the Internationale with which the play began and they liked the music in general. Finally, at the end, a character spoke in Czech and they broke out in relief: someone was saying something they could understand.

Sarka Kapkova and another unnamed resident began to dance in a highly stylized fashion (above). I cannot reduce all this to a simple meaning. It opens up so many wounds and avenues of exploration. The film itself did not end but continued in a permanent loop back past what I take to be the opening title (as above). But perhaps the true beginning is somewhere else. Where we consider what the relations of desire, freedom and revolution might be, should be and can be allowed to be.