In the past weeks since the Debt Assemblies began and led to the formation of the Strike Debt campaign, my relationship to this writing project and to OWS has begun to shift. For a long time, I wrote from the participant observer position. I was there, in the room, often in the square or on the march. But I was not taking decisions or influencing people very much, although I might make the odd comment here and there. Honestly, Occupy and direct democracy were quite a steep learning curve for an academic.

It’s also a somewhat comfortable position, of course, allowing the writer to perhaps imply criticism, although I have always tried to do the harder thing of trying to look for the optimistic or hopeful outcome. Over the past few months since I’ve begun working more closely with Occupy Theory and now Strike Debt, that safety barrier is gone. I find myself questioning whether I have the right to report certain discussions or issues, Or better put, whether I should, not from the point of view of this writing but from the point of view of the movement.

It’s not that I’m party to any secret decisions or that I’m in any way, shape or form a “leader” because there really are no leaders. It’s that I’m not sure exactly what my role is now. Some other writers I know call this “observant participation.” Key here is the acknowledgement that you are writing about the movement as you are also active in it. Unlike most of these people, I’m writing about things as they happen, more or less, rather than for a dissertation, article or book project. It’s not a moral question, although I do respect security culture within the movement and I don’t name people who have not made their writing public. It’s a writerly question: what’s my perspective on this now?

Two other developments impinge on this repositioning. One is that there are fewer people active on a day-to-day basis in OWS now than there were at May Day. A good deal of this is the summer diaspora from New York, and with the climate-changed 97 degrees it was today, no wonder. There are students back home or doing research travel and activists. Others have dropped out, burned out or moved on. So it’s easier to get a sense of the movement than it was when it seemed to be limitless. Perhaps that’s also a coming-to-terms with the sheer difficulty of actually changing this deeply entrenched system.

Finally, it’s the debt campaign itself, which is a re-orienting of my own position. We are all “in” debt, or I certainly am. Mortgage, credit cards, refinanced mortgage. It’s a place of some shame and embarrassment: isn’t a middle-aged, more or less successful person (in their field) supposed to be past all that? Maybe, but I’m not, given a commuting work situation that requires two households in one of the world’s most expensive regions. I assumed getting “out” of debt was a combination of personal discipline and professional success, a Houdini-like escape trick that has eluded me so far.

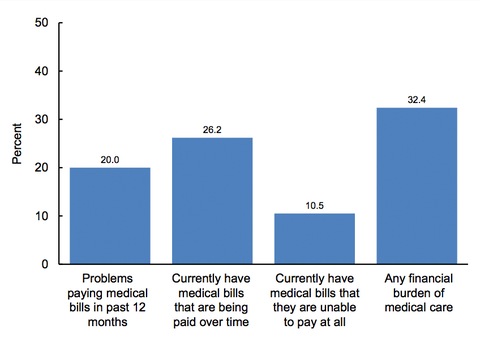

Now I can see that getting “out” of debt requires getting into public space. It means striking debt so that if a corporation is a person and must be bailed out, guess what, I’m a person as well. It’s realizing that if there are 5 million households still under threat of foreclosure, 27% of student debtors behind or in default, and $800 billion of revolving credit card debt, there’s a massive debt strike already taking place. We just haven’t dared to admit it. You are not a loan.