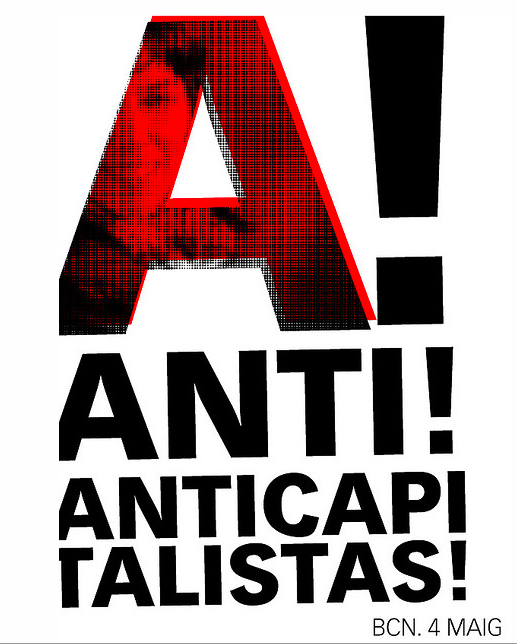

In people’s comments about M17, the six-month anniversary of OWS, you can see a broad agreement that there’s a new feel to the movement. It’s epitomized by the gradual shift in chant preference from “We Are the 99 Per Cent!” to “A-Anti-Anti-Capitalista!” The former is a statement. The latter expresses the new resistance.

In people’s comments about M17, the six-month anniversary of OWS, you can see a broad agreement that there’s a new feel to the movement. It’s epitomized by the gradual shift in chant preference from “We Are the 99 Per Cent!” to “A-Anti-Anti-Capitalista!” The former is a statement. The latter expresses the new resistance.

AAAC–as we’ll call it–is also inherently danceable with a 1-2 2-2-3 rhythm built in. It helps that it’s in Spanish, it feels global and properly hemispheric. Not that anyone has consciously thought this out I suspect. On Saturday at Liberty, when hundreds were celebrating what felt like the re-occupation by singing AAAC, a young woman leaned over towards me and asked “What does it mean?” When I told her she smiled in a way that indicated both pleasure and relief–it was what she thought it was and that felt good.

At the General Strike panel at Left Forum, Mike Andrews–one of the leading figures in the May Day planning group–told a similar story. He described how he had seen a group of teenagers jumping up and down shouting “General Strike!” As he said, it’s unlikely that any of the events remembered by left archivists, whether Seattle in 1919 or Britain in 1926 were in their minds. It’s possible that they didn’t even really know what general strikes have been in the past. Right now, as Mike put it, it means for them: “Fuck my shitty job”–and the desire for something better. Some were clearly surprised by this choice of words but it rang true to this precarious generation.

Natasha Lennard, writing for Salon, also turned to this theme:

There’s no adequate explanation for why, for example, on Saturday, it was beautiful to go back to one of the dreariest slabs of concrete that lower Manhattan has to offer and find nearly a thousand other bodies — dancing, chanting “a-anti-anti-capitalista,” catching up and dashing off into spontaneous street marches.

It’s that “magic” feel of Occupy, the sense of making something different, something resistant to commodification that is the distinguishing factor here, especially from the shouting soap-box orators of the traditional left.

To add my own story, a couple of weeks ago I was in Arizona to give a talk at Arizona State, a place where the University President is aggressively neo-liberal and has hiked tuition dramatically. My hosts were very nervous about the attendance, expecting they said perhaps 12, maybe 20. Much to their surprise, about 150 people showed up for the talk because the word “Occupy” was in the title. After the traditional academic introduction, I looked at this group and said, “Hi, my name is Nick and I’m part of Occupy Wall Street.” The whole room smiled–not for me, of course, but for the idea of Occupy. So we consensed to occupy the room for the next hour and a half.

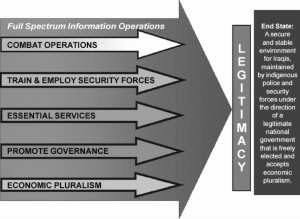

What you can feel here is the pleasure of resistance, not simply refusing to move on, but claiming the right to look at what there is to see here. Look back at September 2011 and there was of course plenty of outrage at the banks and at Wall Street–which is why, after all, it was Occupy Wall Street and not Occupy Lincoln Center. Some of the ideas being floated back then by Adbusters and others included reintroducing the Glass-Steagall Act, creating a one per cent tax on financial transactions and so on. You don’t hear much about those kind of ideas now, although they would have been sensible reforms.

In China Miéville’s photo-essay London’s Overthrow [by the way, the New York Times excerpt cut out all the politics, big surprise, read it online}, he writes

The lion looks out from its apocalypse at the scrag-end of 2011. London, buffeted by economic catastrophe, vastly reconfigured by a sporting jamboree of militarised corporate banality, jostling with social unrest, still reeling from riots. Apocalypse is less a cliché than a truism. This place is pre-something.

Pre-figuring is going on all day, all week. Here’s the logo from Occupy the Movie, currently being advertised online:

The parody of Emmanuel Leutze’s corny Washington Crossing the Delaware was well-timed. This morning the Metropolitan Museum of Art used the painting for a full-page ad in the New York Times celebrating their corporate sponsors, including all the usual criminals from Goldman to Citibank and Bank of America.

They don’t get it. Do you? Do you feel the change?