Looking back over the six-month history of Occupy, it’s surprising to me that one aspect of its project has been understated. The concept of the 99 per cent has been taken to be newly inclusive–and perhaps it is, compared to class warfare of the Stalinist or Republican kind. As a theory of sovereignty, however, it is in fact surprisingly radical.

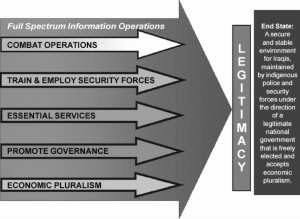

As the name suggests, sovereignty is the theory of the sovereign, the authorization of the ability to operate power. Its fundamental operation in European modernity has been to produce a singular sovereign, whether a person, a nation or a people. Hardt and Negri call this the “sovereignty machine,” the means by which

The multitude is in every moment transformed into an ordered totality.

[Empire, 87]

Whether the state declares itself democratic or not, modern sovereignty always tends to a single form of power.

Consequently, the authorizing form of the “people,” which is in theory limitless, has in practice been highly circumscribed. When the Declaration of “We, the People” was made in 1776, more people were excluded than included in that frame–the indigenous populations, the enslaved, women and children. The nationalist claim of the “people,” as in the obligatory invocation of “the American people,” is similarly exclusive.

Nonetheless, the constant accusation against democracy as a system of sovereignty has been that it is limitless and places too few constraints on its constituents. In Rancière’s pithy formulation

democracy=limitlessness=society.

The anxiety at work here is that the open-ended nature of “the people” might serve to derail the sovereignty machine in its perfect equation of law with property.

For Hardt and Negri, the “people” that must be reduced to what Hobbes called “one will” is always already distinguished from the “multitude”:

The multitude is a multiplicity, a plane of singularities, an open set of relations, which is not homogeneous or identical with itself and bears an indistinct, inclusive relation to those outside of it [103].

The concept of the multitude has been much criticized for this apparent vagueness. However, theological and apocalyptic theories of sovereignty have been received with open arms, as if the use of Latin terms is enough to bring us back to the Church.

Is the 99 per cent, then, the multitude? Unlike the “people,” the 99 per cent does not claim to be fully inclusive or limitless. It claims a right to authority without producing “one will,” and indeed expects to curtail the perfect mirror relation between law and property. The importance of this rupture far exceeds any quarrel with the limit that has been suggested. It is a theory of sovereignty, not of the practice of direct democracy. That is to say, it is not to be expected that 99 per cent consensus will be, or should be, achieved in all assemblies.

At the same time, this articulation of the divide between the multitude and capital in relation to sovereignty is itself a mirror of the new contempt that capital has for its human agents. The fantasy of a market based on Adam Smith’s “self-love” has been replaced by a slasher capitalism that wants to “rip the eyes out” of its own customers, whom it perceives as “Muppets,” according to the so-called scandalous revelation of Goldman Sachs’ internal culture.

This palpable disconnect renders the “image” component of the nation state’s “imagined community” highly problematic. As all the language of mirroring and specularity suggests, the image of the imagined community operates as a supplement: “I am like the nation and the nation is like me.” Only it isn’t. For “white” America, the impossible choice between the one per cent candidate they are told to want, and the image of the Confederacy they actually want, is playing out as farce, which is not say that it is not dangerous, as supplements always are.

For the 99 per cent, there is a genuinely new task: how to image and imagine multiplicity without producing another version of “one will.”