After comparing the first two Communiqués in the OWS theory journal Tidal, today I’m reading the essays by Judith Butler, Gayatri Spivak and Marina Sitrin. I see here an emerging concept of Occupy as the horizontal strike against inequality.

First let’s applaud both the editorial team at Tidal and the authors for this mutual engagement: very few established publications could command such writers for their debut issues and it’s to the credit of these much-in-demand figures that they have prioritized writing for Tidal.

In two essays, Butler develops her approach from an initial stress on the “call for justice” in December to today’s key

claim that capitalism relies upon, and reproduces, social and economic inequalities [that]…are becoming greater, assuming new and devastating forms and [that] this accelerated process of inequality remains unchecked by existing state and global authorities.

If the earlier stress was on the “precariousness” that the global financial crisis has produced, as it were, by accident, Butler now suggests that capital is operating in such a way that labor has become a “disposable population.” We might recall that whereas it once took approximately eighty per cent of the workforce simply to generate sufficient food, contemporary agri-business can do so with only two per cent.

Any small adjustment in the current organization of society would not, then, address “the reproduction of inequality” that can be seen as the intended consequence of neo-liberalism. Here we recall Butler’s evocation in Tidal 1 of the cheering Tea Party crowd when invited to imagine a person without health insurance dying. Or the new waves of hate against people using contraception, marrying each other, or otherwise organizing to defend their equality.

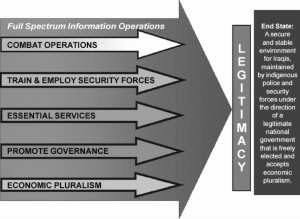

Volumes have been written about the ways in which capitalism has always exacerbated inequality, and treated colonized and enslaved populations as disposable–and it’s safe to assume that Butler, of all people, has read most of them. What she is articulating here is a theory of resistance, and of the means to challenge the legitimacy of such a system. Interestingly, the counterinsurgency promoted by the US in Iraq and Afghanistan was centered on creating just such a legitimacy.

This combination of neo-liberal “economic pluralism” with militarized governance is precisely what is presently in crisis. As David Graeber might say, there is an inherent resistance to such notions, based on his demonstration that “communism is the basis of all human sociability.” By communism, he does not mean in any way the oddity of the Soviet system. It is a general theory of the possibility of society and a particular refutation of the neo-liberal fetish of “self-sufficiency as a moral ideal” (Butler).

As Butler now argues, this contestation of legitimacy is the moment at which Gayatri Spivak’s theory of the general strike becomes so important. She understands the strike as “a collectivity of disenfranchised citizens,” in which citizenship is not a formal case of documentation, so much as the index of membership of a given society. After giving a precis of the various forms of general strike from Du Bois to Gandhi and Luxemburg, Spivak provocatively suggests

[I]n the “Occupy Wall Street” movement the spirit of the General Strike has come into its own and joined forces with the American tradition of civil disobedience: citizens against an unregulated capitalist state, not against an individual and his [or her] regime.

The “spirit” of the General Strike is the specter haunting neo-liberalism. It is not the specter of state-centered command economies. It is a gesture towards the justice that cannot be deconstructed.

Writing with the collapse of Rosa Luxemburg’s Spartacist uprising fresh in his mind, Walter Benjamin, whose spirit pervades Tidal 2, defined the general strike as the event that

takes place not in readiness to resume work following external concessions and this or that modification to working conditions, but in the determination to resume only a wholly transformed work, no longer enforced by the state, an upheaval that this kind of strike not

so much causes as consummates.

In its “American” form, taking America to refer to the hemisphere, Marina Sitrin sees such a strike as something

we are discovering together, as we create, which is also how we create: together, horizontally and with affect. What we are doing and how we are doing it are inextricably linked, and both are part of this prefigurative movement.

What we do imagines, forms and creates what there will be next in place of this present disaster, if there is anything. Sitrin warns, based on her experience in Argentina after the crisis of 2001, against two potential distractions. First, the movement may be distracted from this project by already existing left or centrist parties seeking to use its energy. Secondly, and this will be a real issue once the Republicans decide which puppet best suits their Super PACs, we must guard against the electoral distraction: “vote? not vote? organize against the candidates?” In place of such vacillation, Sitrin offers the powerful slogan

With, Against and Beyond the State.

Which is to say, yes, vote in November as a tactical measure, but organize against the state that continues to be the agent of neo-liberal legitimacy. Above all, imagine and create a practice that is beyond the state.

The Tidal theory of Occupy as a horizontal general strike against inequality is moving and dynamic. It suggests two motifs for the present and some for the near future.

First, all Occupy action is a general strike. We should not get drawn into the numbers game that only a massive shut down of all services and industries would count as such a strike. There has been such a strike in North America since September 17, 2011 and in the Americas since the first indigenous revolt against the settlers and the first uprising by the enslaved. MayDay 2012 is a celebration of the return of this spirit of the general strike, not its coming into being. It grows as it turns, yes, but no one instance will be transcendent.

Next and by corollary, the state against which we strike is strong and weak at the same instant, which Negri has called “the porcelain effect.” Porcelain is both very resilient and breakable at once. It endures right up until the moment that it does not, as we saw most recently in Egypt. This is why it cannot be reformed: you cannot recast porcelain once it has been fired, you either use it or discard it.

For the future: Tidal can and should drive this debate, becoming the locus of a new discourse on the horizontal strike against inequality that prefigures what we are creating. There are questions in the spirit of the general strike as to the practice of direct democracy, the recognition of climate injustice and the rights of the non-human in the midst of what has been called the Great Extinction.

For the time being, let’s salute the work already done and the impetus it gives to us all.