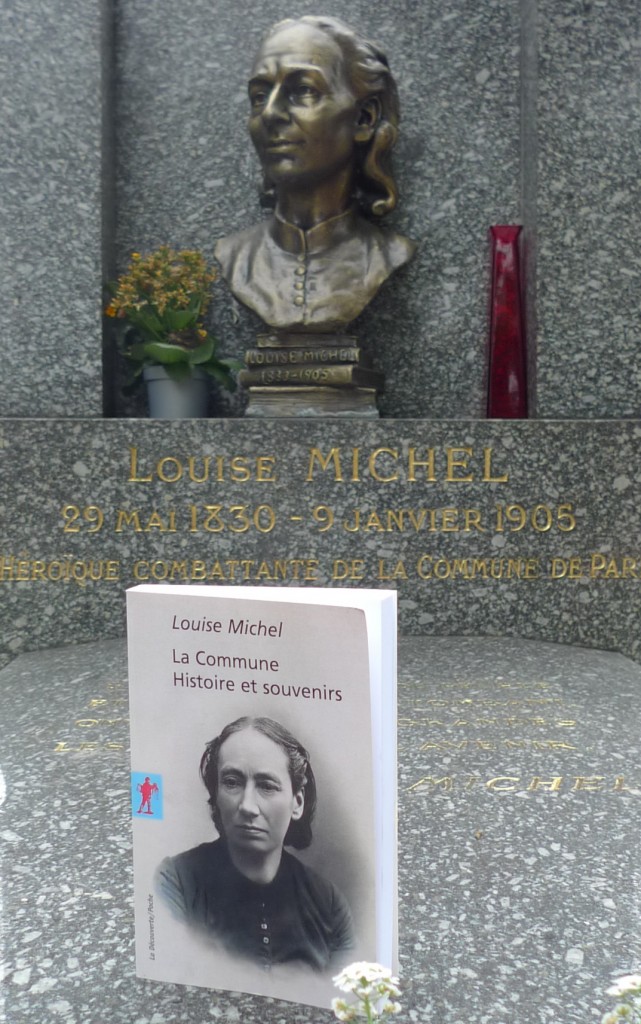

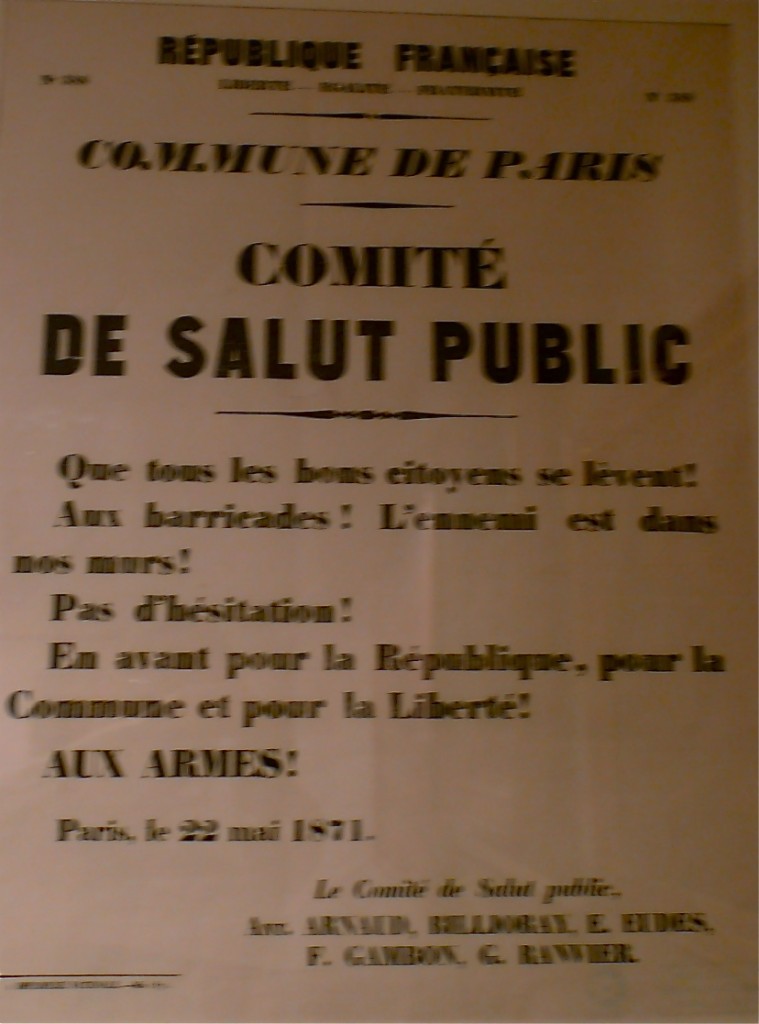

So what happened? While we were expecting a strong showing from the radical left in France, we got an unexpected surge by the racist National Front, and a less-than-predicted turnout for the Left (I exclude the “Socialists”). It seems that some of those who claimed they would vote left actually voted for the Front, because they know that such positions are disgraceful, but they hold to them nonetheless. Somehow, and this is the fallacy, it seems more disappointing from France because of their revolutionary heritage: let’s consider some of that legacy.

So because we don’t have good information on what has happened yet, today seemed like a good day to look at Rancière’s lessons from the contradictory aftermath of 1968, following from the discussion of his interview yesterday. I spent much of the day traveling (I’m on Central time for a few days) and read through several chapters of the recently published translation of his 1974 book Althusser’s Lesson. Rancière’s example shows how the force of a political rupture can change long-held positions: and the risks of such a change.

This book is part Oedipal separation from the bad father, part political testament and (unwittingly) part evidence of how not to deal with a crisis of political belief. Rancière was one of those who worked with Althusser on Reading Capital, published in France in 1966. When the events of 1968 unfolded, Althusser took a now notoriously qualified position, in keeping with that of the French Communist Party (PCF). In 1973, he published a long essay called Reply to John Lewis, a pseudonym used by a writer for the Communist Party of Great Britain in a set of attacks on Althusser published in the Party’s theoretical journal Marxism Today. Althusser’s response reasserted the theoretical position that seemed to have been undermined by 1968 and provoked Rancière to break with his mentor.

As he puts it in the Foreward to the English Edition,

I wrote the book as the efforts to give long-term life to the rupture of 1968 were succumbing to exhaustion and as the resulting disenchantment was taking the form of a radical critique of militantism.

Such critiques were double-edged: there were resistances to “its male and patriarchal forms of power” that most of us would agree with, while others denounced the entire revolutionary tradition in the name of the Stalinist Gulag. The key question for Rancière was not how to revive Marxism but an analysis of

the much broader logic by which subversive thoughts are recuperated for the service of order.

In the original text, he notes that Althusser’s return to orthodoxy came at a moment when post-68 radicals were defending the occupation of the Lip watch factory in Besançon and a union-based assembly against a military base in Larzac.

In the new Foreward, he puts the stakes thus posed unusually bluntly, stating his opposition to the idea that

the dominated are dominated because they are ignorant of the laws of domination….assign[ing] to those who adopt it the exalted task of bringing their science to the blind masses. Eventually, though, this exalted task dissolves into a pure thought of resentment which declares the inability of the ignorant to be cured of their illusions.

Rancière took the opposite approach, which based itself on the

inverse presupposition, that of the capacity of the dominated. It did so at the price of identifying this capacity with the slogans of China’s Cultural Revolution.

So while I can agree with the supposition, it’s sobering to realize that it was done in the name of such Maoism. It’s easy to see why he is now cautious about identifying his work with actually existing radical politics, having made a category error of such disastrous proportions. The important thing is not to throw his work out with the Maoist bathwater but to accept the Benjaminian lesson he draws:

there is no theory of subversion that cannot also serve the cause of oppression.

What does this history imply? It means that it is possible for a group of French voters to agree with a left critique of neo-liberalism: and then respond to the fascist solution. It does not mean they are stupid or puppets, but that we have not yet understood the way they visualize their situation to themselves. It suggests that there are not going to be what Rancière calls “‘heroes’ of theory,” who will solve such issues for us. If, as Rancière reads Marx, it is still possible

to invent a new world through their [the workers] barely perceptible gestures

then our interest is in how such gestures can be felt, seen and understood. And we would say yes to his 1974 claim to

contest the authority of knowledge on a local scale

while wanting to refuse

Cultural Revolution on a global scale.

I’m all for a revolution in culture that results from local contestations of authority. I don’t think we yet know what that means on a global scale, or even what the global scale would be. For Occupy, then, having again managed to reopen the question of authorizing authority, the time of defining a response has not come. Indeed, the longer it is postponed, or even permanently displaced the better, I suspect. It took five years for the 68 movement to become exhausted. Even if we assume that time passes more quickly these days, we’re not done yet.