This time last year was D17, a day when OWS tried to establish a new occupation at Duarte Square, land owned by Trinity Wall Street Church. The effort failed and Mark Adams spent 30 days in Rikers Island on exaggerated criminal charges resulting from the plan to cut back the fence that the church had put up. It seems so much more than a year.

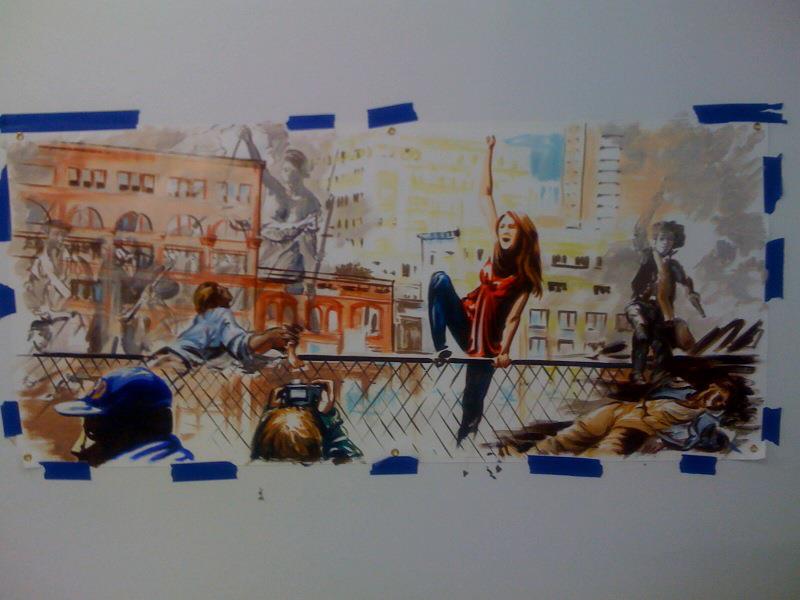

Morgan Jenness has produced this rather wonderful artwork to commemorate the anniversary.

The vision here blends Delacroix’s 1832 classic painting Liberty Leading The People with the New York skyline and the Duarte fence. Ironically, the painting itself was also recently evicted out of Paris and sent to the Louvre’s outpost museum in Lens.

Lens is a depressed former industrial city in Northern France. One Parisian I asked why they had sent Liberty up there replied dryly: “Now everyone’s unemployed, they thought it was time for them to get some culture.”

Lens is a depressed former industrial city in Northern France. One Parisian I asked why they had sent Liberty up there replied dryly: “Now everyone’s unemployed, they thought it was time for them to get some culture.”

Back in New York, the remembrance of a year ago brings back how absolutely vital it then seemed to continue the occupations as encampments. I don’t mean to disparage–the encampments were so amazing and nothing that has happened since would have happened without the experiences we had there and what was learned. A year on, and that self-fashioning into a community of mutual aid has blossomed in ways that we could not possibly have anticipated back then.

That’s why events like the Winter Jubilee are so important as a way for us all to check back in with our own “beloved community” from time to time. People are working with Occupy Sandy, in militant research, in the Rolling Jubilee and other projects and we don’t necessarily connect with each other. Of course, that was the beauty of the park, that the other working groups were just there. But if you’re building a movement, then or now, there comes a point where you can’t all fit into one square all the time.

As we put what we have learned into practice, it is borne in on us every day that the one per cent is still determined to foist the crisis onto us, to use every violence at their disposal to make sure that it remains that way, even to the point of trying to block relief aid for the victims of Hurricane Sandy, let alone banning the murderous weapons that kill people each and every day.

We’re still climbing fences. They’re just a little higher now.