In the first paragraph of The Right to Look, I wrote:

The right to look is not about seeing. It begins at the personal level with the look into someone else’s eyes to express friendship, solidarity, or love. That look must be mutual, each person inventing the other or it fails. As such it is unrepresentable. The right to look claims autonomy, not individualism or voyeurism, but the claim to a political subjectivity and collectivity: “the right to look. The invention of the other.”

I didn’t say much more about love in the book, partly because I wanted to avoid the imputation of voyeurism and all the other issues to do with the gaze. It was also hard to configure the narrative around the politics of autonomy with the questions raised by the look of love.

While the difficulty of narrative remains, I now think it was a mistake to underplay the power of the exchange of looks that is love. It resonates with audiences when I give this as a talk because it is something with which many are familiar and it makes sense of the difficulties of representing that exchange.

With the hindsight of Occupy, two further ways of expressing the right to look in and as love should have been developed: the hierarchies of patriarchy that prevent visualized expression of love; and the interface of poverty and love that produces the desire for democracy.

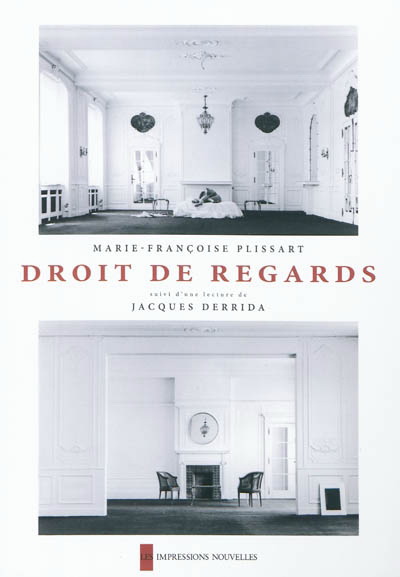

The phrase “the right to look” is my translation of Derrida’s droit de regards, often (oddly) translated as “rights of inspection.” Derrida was responding to the complex relations of looking at work in the photographs of Marie-Françoise Plissart.

The cover shown here is from a recent reissue. Plissart’s images show two women in pursuit of each other, making love, escaping from men. Derrida’s suggestion is perhaps that in the context of 1983, eight years after Laura Mulvey had first published “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” it was between women that it might be possible to allude to the right to look. For a man looking at a woman would too easily become the other translation: the law of the gaze. The photographs seem a little dated now. Would that we could say the same about patriarchy.

Both Jacques Rancière and Antonio Negri develop the relationship of democracy to desire. For Rancière, the palpable “hatred of democracy,” which he describes in his book of the same name, in Western culture is motivated above all by the detesting of “the limitless desire of individuals in modern society.” By contrast, “good” democracy is about controlling and restraining both the extent of democracy and the passions of the individual. Thus the revisionist interpretation of the 1968 revolution is that it “really” expressed a desire for consumption. One could push this to it conclusion: a revolution is the love for democracy, a direct democracy between people that does not defer to representation.

This is precisely the move made by Negri in his poetic and philosophical text Kairos, Alma Venus, Multitude (translated in a volume called Time for Revolution). This is not the kind of writing one can easily summarize, building layer upon layer and allusion to allusion. The kairos, the instant, is something like the time of the right to look: always now, always predicated to the future to come. The “poor,” or “those most exposed to the immeasurable” are the “biopolitical subject.” For unlike the emphasis on population or bare life in other readings of biopoltics, Negri stresses that it is “poverty that has always represented the common name of the human.”

The Kairos of the poor is love:

so what is “politics” today? It is the activity of production of the common name between poverty and love.

Happy Valentine’s Day.