I’m revising two pieces that I’ve done about Occupy, one from last October, the other from January. It’s odd how long ago they seem to have been written, while at the same time making me realize how short a moment this really has been. Movement time is like that: it extends the present, makes new pasts available and yet questions the future.

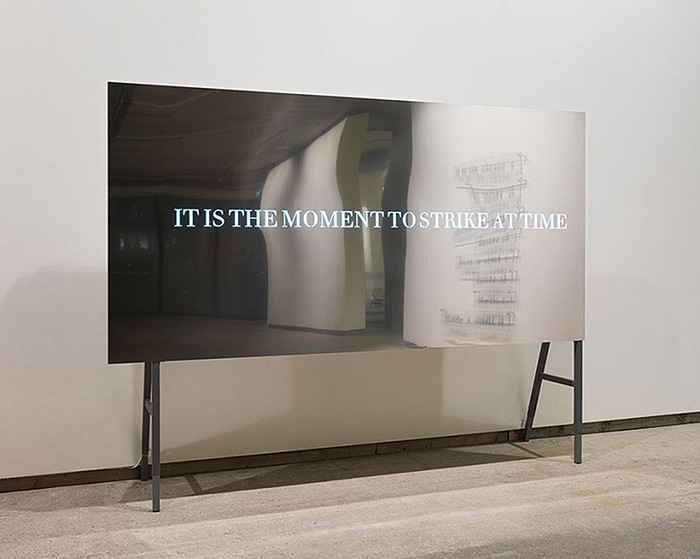

I began thinking about this when I illustrated the piece about Sarai with the Raqs Media Collective’s work “Strike.” On a sheet of stainless steel is written: “IT IS THE MOMENT TO STRIKE AT TIME.” The slogan seems entirely conventional until the last two words: how do we strike at time? Who are the strikers and who would be their target? There have been many strikes about time, usually time to be worked in exchange for a wage. There are those Spanish Civil War anarchists, evoked by Benjamin, who shot at the clocks that made their alienated labor measurable. Back in the 19th century, people had to be taught how to regulate their lives by the clock, that they could not sleep in “work time,” let alone drink.

Then there’s the steel, shiny enough to be reflective but, at least in the photo, not without distortion. Perhaps surprisingly, there’s a formal resemblance to Anish Kapoor’s work here. It made me think of the complexities of steel as a form of labor. I’ve been following the strike and occupation by steelworkers at the ArcelorMittal in Florange, France. Last Friday, 17 workers from the plant completed a symbolic walk from Florange to the Eiffel Tower, symbol of Paris and modernity, built from Lorraine steel. Everyone knows this is going to end with them being made redundant but officialdom continues to prevaricate until the elections are over. New polls show the National Front winning among young people. Meanwhile, as covered before, Kapoor is creating a new monument for the 2012 Olympics paid for by Lakshmi Mittal in London, the Eiffel Tower for autoimmune capital.

Raqs also have another piece referencing steel and shipyards. The elegiac image above shows cranes being dismantled in the famous Swan Hunter shipyards of Newcastle-upon-Tyne in England, prior to being sent to India. The enigmatic title of the seven-screen installation “For the Knots That Bind Are the Knots That Fray” has been proved right recently, when the purchaser of the cranes, Bharati Shipyard in Bangalore itself appeared to face bankruptcy, unable to pay its debts.

Raqs also have another piece referencing steel and shipyards. The elegiac image above shows cranes being dismantled in the famous Swan Hunter shipyards of Newcastle-upon-Tyne in England, prior to being sent to India. The enigmatic title of the seven-screen installation “For the Knots That Bind Are the Knots That Fray” has been proved right recently, when the purchaser of the cranes, Bharati Shipyard in Bangalore itself appeared to face bankruptcy, unable to pay its debts.

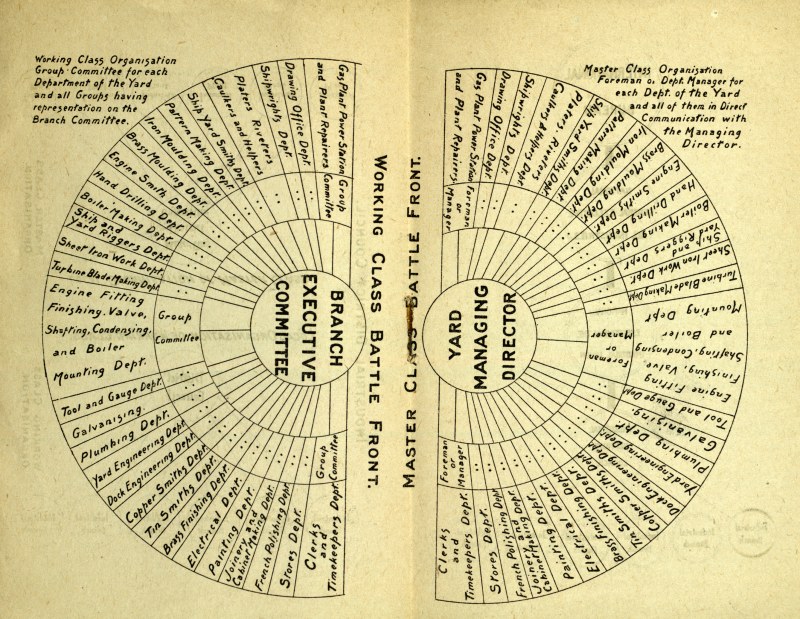

Behind such iconic modern forms lies a long history of the strike. On Glasgow’s Clydeside, the steel and shipyards formed the heart of the British labor movement. In a 1917 pamphlet called Industrial Unionism, the Industrial Workers of Great Britain visualized their situation as a battlefront.

The Working Class and Master Class were mirror opposites, as if anticipating the shiny reflection of Strike. The IWGB was a branch of the IWW, and called for the abolition of wages, direct action, rent strikes and eventually in 1926 Red Clydeside was a key player in the General Strike of 1926.

Fast forward to 1971: after fifty years of class struggle, the workers at the Upper Clyde Shipyards on Clydeside faced redundancy as the government sought to close the yards in what can now be seen as the first wave of neo-liberalism. Instead of the expected traditional strike, which would have led to a lockout and acceleration of job losses, the unions occupied the shipyard, did no damage, and in the famous words of Communist shop steward Jimmy Reid, there was “no hooliganism, no vandalism and no bevvying (drinking).”

A placard in this photograph prefigures the 1984-5 miners’ strike that would be the turning point of Thatcherism: the “Jobs Not Dole” slogan on the far right clearly anticipates the later “Coal Not Dole.” The shipyard workers staged a march of 80,000 people, gained worldwide support, including that of John Lennon and used public opinion to save thousands of jobs. With the possibility of Scottish independence on the horizon with the referendum of 2014, and as jobs disappear at the behest of the bankers, such histories seem newly meaningful. Yet while two shipyards were saved, the departure of heavy industry from the U. K. and the construction of a permanent underclass was just delayed.

But none of the imagined futures in these strikes against time have quite come to pass. While the 1926 General Strike was repressed, its victors were themselves defeated when the 1945 Labour Government implemented the welfare state. Its creation of free state higher education, for example, lasted over fifty years. Nor do the Indian capitalists who dismantled the Swan Hunter yard look so clever now, a mere two years later.

So if the victory of the “Master Class” is shorter now, there’s also a longer rhythm at play, in which the anarcho-syndicalist demands of the IWGB for the abolition of the wage-system by direct action once again feels right. The proper lesson, then, is the future will be seen as the future precisely when something happens that we don’t expect or anticipate. To that extent, the future is always ours, not theirs, because the way it happens now is how they feel it always ought to be.