Why are there white people in the Americas? One way to answer that question would be: fish. Cod and other fish drew early visitors here, especially to Newfoundland. Later sailors reached Massachusetts, where the cod were so plentiful that to catch them you only had to throw a bucket over the side of the ship. They called the place Cape Cod. All those fish are gone.

We are now in the midst of what scientists call the sixth Great Extinction. Unlike earlier disappearances, this one has a single cause. Human actions in the pursuit of industrial capitalism have put at least 20,000 species on the high-risk “Red List” for extinction. Yet when the New York Times ran an op-ed on this today, the biologist Richard Pearson felt the need to render this as an economic problem:

the total economic value of pollination by insects worldwide was in the ballpark of $200 billion in 2005. More generally, efforts to tally the global monetary worth of the many different benefits provided by ecosystems come up with astronomically high numbers, measured in tens of trillions of dollars.

If we cannot find better ways to imagine why the total eradication of tens of thousands of living creatures should be prevented, we make the case for our own disappearance. That “we” hides something, though: those that did this from the industrialized nations, mostly “white,” are visiting this on the entire planet, mostly not “white.”

Over the course of the visual culture conference, the visualizations that stayed with me most were two videos presented by the performance artist Patty Chang. In 2011, Chang had a residency on Fogo Island, off the coast of Newfoundland, one of the most Easterly places in the Americas. It was for a long time home to a major fishing fleet but as a result of overfishing, that’s all but gone. Instead, tourism and, of all things, art are being promoted as alternatives.

Fogo is a place that is also known for its whale populations.

On her visit, Chang walked to the far side of the island, where she encountered the beached corpse of a sperm whale. The body was white, which she later revealed was due to decomposition. Nonetheless, she went into the shallow water where it was lying and washed it, a ritual for the dead common to many religions. From the place where she shot the video the whale seemed at once whole, uncanny and spectral. The performance was riveting.

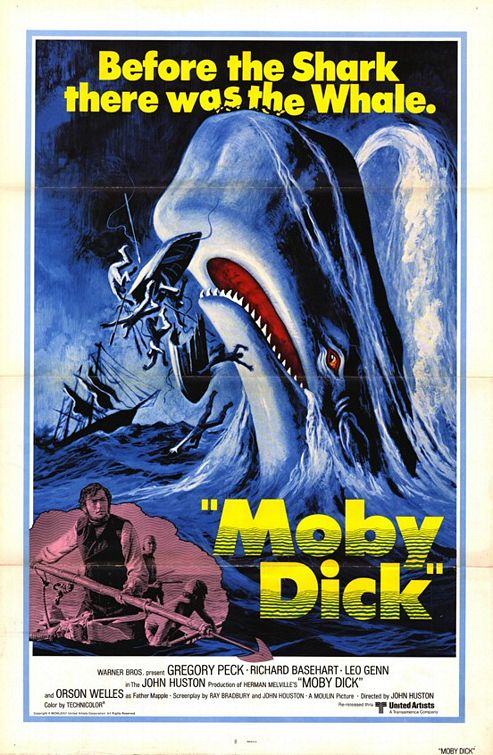

Photographed here by the artist Tonja Torgerson, the whale was clearly decaying and Chang said in discussion that it smelled appalling. In her talk, though, she linked this white whale to Moby-Dick and Melville’s great allegory for capitalism. In the conjuncture of fishing and whaling, we might want to break this up, so it reads “the white(s) (and the) whale.” Among many references, she showed the poster for the classic film starring Gregory Peck:

There are so many odd things about this, it’s hard to know where to start. The 1950s were saw mass whale hunting for food and oil that brought many species of cetaceans close to extinction. We think of whaling as a remote form of environmental damage. Rather, it was nuclear. It was A-bomb devastated Japan that turned to whales as food and refuses to abandon them now as a mutant form of decolonial resistance. The caption appears to anticipate that audiences for the 1956 film have already seen Jaws, Stephen Spielberg’s 1975 shark movie. The White Whale is represented as a hybrid between the phallus of the male gaze and the castrating vagina dentata that haunts its dreams. At the same time it proleptically anticipates the creature in Alien (1979) as it emerges from its human host.

There are so many odd things about this, it’s hard to know where to start. The 1950s were saw mass whale hunting for food and oil that brought many species of cetaceans close to extinction. We think of whaling as a remote form of environmental damage. Rather, it was nuclear. It was A-bomb devastated Japan that turned to whales as food and refuses to abandon them now as a mutant form of decolonial resistance. The caption appears to anticipate that audiences for the 1956 film have already seen Jaws, Stephen Spielberg’s 1975 shark movie. The White Whale is represented as a hybrid between the phallus of the male gaze and the castrating vagina dentata that haunts its dreams. At the same time it proleptically anticipates the creature in Alien (1979) as it emerges from its human host.

Alien was haunted by capital (The Company), insurgency and empire. And that form of alienation is about to return as Ridley Scott cranks up the franchise once more with Prometheus.

Chang’s performance ended with another extraordinary visualization. She took a journey across Central Asia, encountering among many other things, a legend that all Uighurs are descended from wolves, like the legend of ancient Rome. All these creatures, these compound beings, were part of Hobbes’ evidence for the representational power of the European colonial imaginary (discussed last week). It seems to have lost control (of itself).

Chang finds herself at the Aral Sea, a formerly immense inland lake that has been turned to desert by engineering projects diverting water for human needs. Just like in Newfoundland, there is symbolic death and the disappearance of a primary food source. Chang showed boats now beached on flat endless sand. Once again, in a powerful repetition, Chang set about washing the boats, mourning the loss of natural environment, human livelihood and unknowable numbers of non-human species.

In this photograph of a similar scene from the Aral Sea, the boats look the same but the sand seems slightly less flat–but you’ll get the idea:

The Russian Empire has followed its Cold War partner into a hallucinatory present that it cannot imagine to itself.

The Russian Empire has followed its Cold War partner into a hallucinatory present that it cannot imagine to itself.