“We interrupt this writing project to bring you this message.” How our relationship to advertising (or messaging) has changed. When I began a course in visual culture or media studies, one of the exercises I used to perform would be to ask people in the group: who felt that they were influenced by advertising? Normally, hardly anyone raised their hand. Then I would ask who felt that other people or “ordinary people” were influenced by advertising and everyone would raise their hand. It was supposed to be learning moment. When I have tried this exercise since the rise of social networks, the mask has fallen. Everyone raised their hand and accepted that they were influenced by ads.

One index of this change has been the shift in “must-see” TV for media studies people. While The Wire had its day (2002-8), complexity, urban politics, crime and long-form narrative seemed to have migrated from 1970s cinema to the television drama. The past five years have belonged to Mad Men, a TV show about advertising relying on advertising revenues, in which the sexiest moment is “the pitch.”

That is to say, the moment when Don Draper (Jon Hamm) presents his narrative of a commercial seduction to the clients. There’s much more in the pitch than the ad itself. While the series is soap-like in its narrative format, these moments are lingered over lovingly. Half of the last series hinged around the pitch to Jaguar cars, for which one character prostitutes herself, another commits suicide, still a third comes to existential crisis, while a fourth quits the company.

What was this magical tag line: “At last. Something beautiful you can truly own.”

This kind of message has a weird form of overlap with Occupy messaging. It uses a direct address to the viewer and it claims beauty. While Occupy would never associate beauty with a one percent commodity like this car, the interface should not be denied. After all, the Mad Men screenwriters have 2012 mentalities.

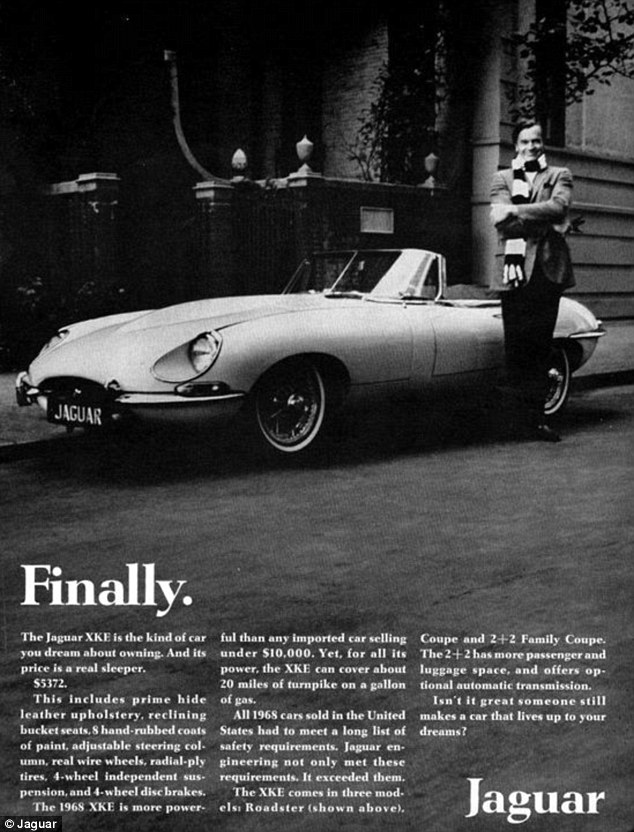

Compare an actual 1968 Jaguar ad:

“Finally,” it says. “The kind of car you dream about owning.” In 1968, year of global revolution, a tweedy self-satisfied young man looks at the viewer in the ecstasy of ownership. The motif of sexualized domination is there but subliminal. The ad addresses men as men without referencing unavailability. In 2012, a year of global social movements, that element needs to be foregrounded to give “nostalgic” satisfaction. So successful has this “pitch” moment been that AMC have commissioned a reality to follow Mad Men called The Pitch, featuring two advertising companies competing for a client.

Against this layered moment of actual messaging with faux-sophistication–sexism in the 1960s is supposed to show “we’ve come a long way, baby” while also indulging the presumed male viewer in its pleasures–how can a social movement address those it would like to participate? Most seem to think that simplicity and directness are the key. Certainly, the “We Are the 99%” meme moved Occupy to the front of media attention.

The difficulty is that we don’t want people to buy something but to do something. Recently I sat next to a friend watching TV when one of the NY State anti-smoking ads came on, featuring people with horrific post-surgical disabilities caused by smoking. She shied away from watching, which I presumed was revulsion at what might happen to her as a smoker. But in fact it was because any ad that mentioned smoking made her want to smoke and she’s trying to quit. Here of course the State gets to have the best of both worlds: it can claim a public health campaign that looks effective to the non-smoker, while encouraging its smokers to consume and thereby raise state tax revenues.

What made “We Are the 99%” so effective was, then, precisely that it did not have content. Each person could decide how it worked for them, just like any effective message. What happens once a tag has circulated endlessly across a show-me-the-money culture for over a year? On September 17, we’ll find out. We may be surprised.