A group of us had fun today trying to dream up some new images for the movement using the words “imagine” and “resistance.” We came to think about hands, as a symbol for the movement and as a means for its enactment. It’s a hands on process and that tells us something–about how we have reclaimed the hand as a tool but also about why the movement unfolds organically, rather than virally.

From the facilitation question “if you can hear me, clap once,” to the standard-Occupy issue notebook, it’s all about hands.

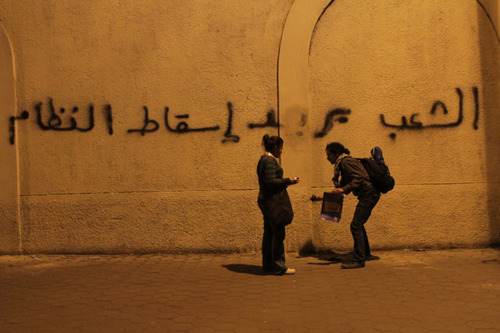

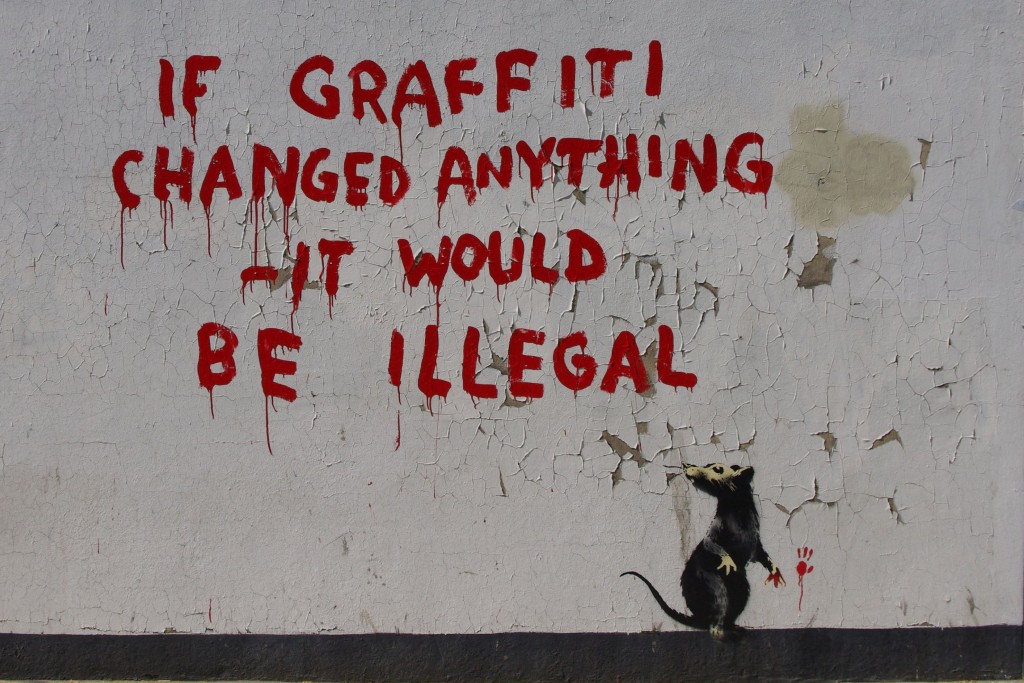

The discussion began with the role of graffiti in the Syrian uprising. People simply wrote their names, a reclamation of the self that is fundamental to graffiti. Autocratic regimes arrogate to themselves even the power of the name. And, as Banksy puts it:

The interface of the hand with the wall produces a form of reclaimed public space, even though walls are designed to exclude and mark the limits of property.

Using stencils, Banksy has been able to expose the separation strategy of the military-industrial complex with this piece on the Israel-Palestine separation wall. The real Palestinian boy on the foreground confronts his graffiiti-ed counterpart and the illusion of open space.

On the other hand, as it were, graffiti artists operate in secret, concealing their identity. They are answerable to their audience, of course, in terms of reception but not directly. The reclamation of the self through Occupy was clearly different in that it was face to face but related in that it was a conversation of hands and eyes. There were the famous gestures of the GA and other meetings. I think here more of the hand-held video cameras, the clinking of the casseroles, painting signs, chalking, gardening, writing, cooking, knitting, and other hand-driven actions of Occupy.

In feudal law, and indeed in marriage, we give our hands to others. In the British navy, ordinary sailors were known as “hands,” as in the command “all hands on deck.” From there, it became a way of describing industrial and plantation workers (meaning slaves) as early as the seventeenth century.

We reclaim not these hands but the hand of the artist visible in her work, the hand offered in applause, the hand noted for its craft or skill and so on. For all our digital communications, this is an artisanal movement, passed on from person to person, hand to hand. It’s a touchy group, meaning that people touch, not that they are short-tempered. Without a “party” to join or other mass form of adhesion, Occupy is a manual process.

I’m reminded of 19th century craft anarchism and socialism of the William Morris variety here. While his pursuit of hand-made high quality materials (above) later seemed wildly out of touch with “ornament is a crime” varieties of modernism, I see people looking again at E. P. Thompson’s classic biography of Morris–here’s a quote to whet the appetite:

In the next few years a rash of Anarchism was to appear in one major city after another. It took all sorts of shapes and colours: there was the sober group around Kropotkin and Edward Carpenter, which published Freedom; there was the studious and restrained old friend of Morris, the tailor, James Tochatti … who (after 1893) edited Liberty; there was the old Autonomie Club, in Windmill Street, where foreign refugees hatched real conspiracies: the Jewish Anarchist Club in Rathbone Place; the Christian Anarchists, the Associated Anarchists, the Collectivist Anarchists, Socialist Anarchists, the followers of Albert Tarn and those of Benjamin Tucker. Papers published, on blue paper, red paper, and toilet paper, ranged from the Anarchist, Commonweal, Alarm and Sheffield Anarchist, to the Firebrand, Revenge, British Nihilist and Dan Chatterton’s Atheistic Communistic Scorcher.

Now there’s a reading list to conjure with! And a forgotten set of histories to remember and fit into our sense of what this movement might be. Let’s give ourselves a big hand.

And a little something, not on hands but graffiti. http://www.burnaway.org/2012/07/our-front-porch-art-under-the-oddest-circumstances/

You will love this work by Sarah Alford about a figure involved in both the arts and crafts and labor movements in Chicago. http://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/11423/11424