Today a symposium at Artspace, Sydney, called Another World drew together art practice and activism. The talk ranged from Sydney to Germany, New York and elsewhere. There was a notable retreat, I’m glad to say, from such terms as “global art” towards questions of politics, debt, ecology and situatedness. We learned about time, to take our time, that this is our time and it is, of course, past time.

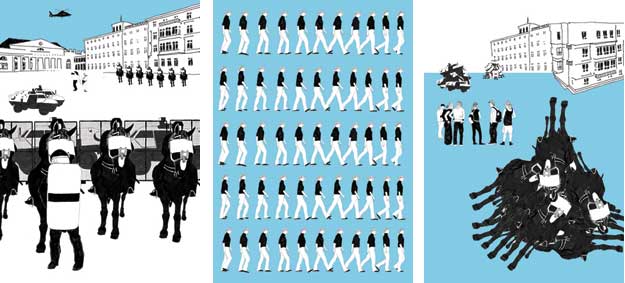

An artists panel in the morning featured an interesting contrast of global and local. Zanny Begg talked about her video with Oliver Ressler What Would It Take to Win? (2008)–the link leads to the entire piece. It covered the global justice movement protests in Heiligendamm (June 2007). What was interesting from the current perspective was to see the force of making no demands: wanting “wins” undermined the global justice movement. Whereas Occupy has been able to reclaim space and, crucially, time.

In that long time that it takes us to get anything done, an aesthetic relation is created between the people doing the action, whatever it may be. A project like the Rolling Jubilee, to buy and abolish debt in the name of OWS, might be an art work. Indeed, the curator Tom Polo mentioned a work in his show There’s a Hole in the Sky, now on in Campbelltown called “Commerce.” The artist purchased items from local bankrupt people, using his art budget, is currently displaying them and will give them away at the end of the show. There’s something very evocative about that action, in a part of Western Sydney that is known for high levels of bankruptcy.

In his afternoon talk, art historian Terry Smith contrasted different approaches to evoking the planetary. He called on Jorge Macchi’s work Blue Planet currently being used as the emblem for the Sydney Biennale as exemplary such refiguration. Macchi creates a “figure of the planetary” (Spivak) by emphasizing the oceans over the continents.

Elsewhere in in the Biennale, Smith found little to like with the exception of several projects, such as Jananne Al-Ali’s video project Shadow Sites II (2010) [see below],

a film that takes the form of an aerial journey. It is made up of images of a landscape bearing traces of natural and manmade activity as well as ancient and contemporary structures.

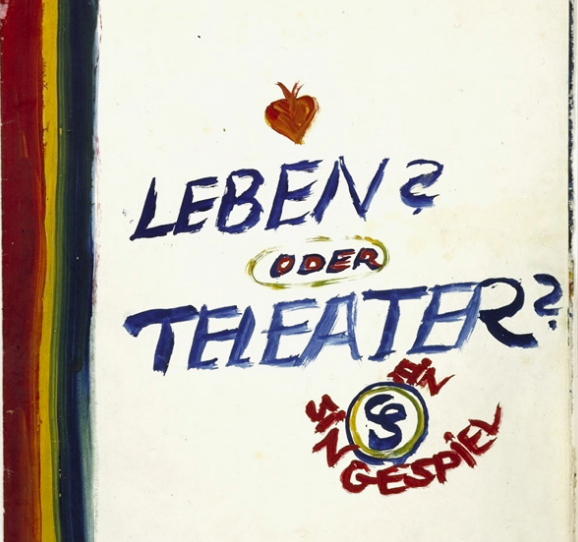

By comparison, Smith suggested that Documenta 13 in Kassel stresses the multiple temporalities of the contemporary. One claim caught my attention: that being on stage (I would say in public) actually creates time. The exhibition includes historical artifacts on this theme, like Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre?, her immensely powerful treatment of National Socialism.

I do worry a bit about this, about always using National Socialism as “history” but the exhibition is in Germany and does feature work describing Kassel during the Third Reich.

The center of the show, according to Smith, is an installation called The Brain, centering on works impacted directly by war:

objects like two wonderful Giuseppe Penone stones, small Bactrian princess figures (2500 b. C.), six Giorgio Morandi still lifes, damaged objects from the National Museum of Beirut, a towel stolen in 1945 from the apartment of Adolf Hitler or masks made from iPad wrappings by Judith Hopf.

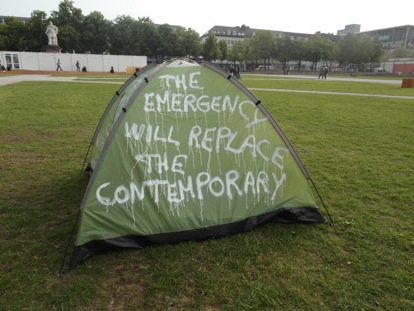

They even had a token Occupy space, a segment of the Documenta grounds turned over to a small encampment.

Together with the Berlin Biennale use of Occupy as a sideshow, this represents a clear, if not terribly important, attempt to co-opt the “cachet” of Occupy to render an art exhibition “political.” An occupation that is limited in time and space is just a zoo.

What did I take away? Moving past the politics of the “win” to a politics of transformation is a slow politics. It moves paradoxically quickly but it consumes time, takes time away from labor and leisure time alike. More pertinently, it tries to abolish that distinction. For the artist or the writer, there is no greater pleasure than “working.” A slow politics would allow that privilege to all.

Would horizontal thinking be the same as lateral thinking?