Bird watching in Central Park is the latest thing not to do while being Black. NYC Audubon Society board member Christian Cooper asked his namesake Amy Cooper to leash her dog, as required to protect the wildlife. Instead she saw him, not as a person, but as a type, “African American,” as if it was her observing wildlife. Her racialized seeing transformed his spoken request into a violent assault. As used by John Joseph Audubon, for example.

For there are many layers to racialized seeing. Some racist theory can lie beneath familiar categories, like popular culture or advertising for decades, only to suddenly (re)activate, like the racist association of masks with muzzles used for the enslaved. But natural history is always there, with its concept of a hierarchy of the human. And, yes, even birds.

If there was a long historical irony behind the Audubon Society anti-racist statement defending Christian Cooper, there is also a belated recognition that such basic precepts have to be asserted, by people identified and identifying as white, even and especially from such “neutral” spaces as ornithology, until they are, finally, absorbed. The Audubon Society website glosses over their figurehead’s involvement with slavery. Let’s correct that.

American ornithology can’t be understood without Audubon’s Birds of America, a multi-volume assemblage of enormous color plates and a text mingling natural history with autobiography and travel narrative. Audubon’s is an all-American story of debt, reinvention, violence and white supremacy. Born the illegitimate son of a Jewish servant to a planter on Haiti before the revolution, he became a bankrupt slaver, haunted by the double loss of slave-generated wealth. As his last two enslaved persons paddled him down the Mississippi River to New Orleans so that he could sell them, Audubon was “inspired” to become a bird artist and taxonomist. Like many 19th century amateur naturalists, he invented many more species than are now accepted. Including the fugitive from slavery.

Scenes of Enslavement

In 1831, Audubon observed what he called the Snowy Heron near Charleston in South Carolina. He saw them in flocks of hundreds of birds. As he observed, they reach as far north as Long Island, where I still see them, only now in twos and threes.

In the background, Audubon painted a plantation and himself, out shooting birds as usual. The plantation was Rice Hope, in Moncks Corner, South Carolina, where the enslaved cultivated rice. None are to be seen here. Instead, Audubon, oddly masked in modern style, is out hunting. The bird metonymically represents all this: settler colonialism, the Second Amendment, white supremacy, and the invisibility of African American labor. You can buy originals and reproductions all over the internet, teaching racialized vision, one print at a time.

Audubon casually shows how practices of enslavement affected even common songbirds. The blue jay was a prolific species with a habit of eating crops, so that in Louisiana

the planters are in the habit of occasionally soaking some corn in a solution of arsenic, and scattering the seeds over the ground, in consequence of which many Jays are found dead about the fields and gardens.

Audubon, “Blue Jay,” Ornithological Biography 1834

Audubon did not need to mention that Louisiana planters were slave owners but followed this account with a fantasy entitled “The Runaway,” also set in Louisiana. Audubon imagined that as he crossed the bayous, he was challenged by a maroon, a fugitive from slavery. But from “long habit of submission,” the fugitive at once calls him “master.” They travel to the fugitive’s hideout in a canebrake, a thicket of grasses reaching over 20 feet. Here Audubon hears the story of how the fugitive was sold, following his “owner’s” bankruptcy, as were his wife and children to different purchasers. Determined to reunite, the fugitives escaped but now they lacked food. Audubon’s reverie ended with him leading the fugitives back to slavery, where they were repurchased by a friend.

As so often, Audubon was repurposing his own history. He was the slaveowner who had become bankrupt and sold his people in New Orleans. Perhaps, too, he was remembering vaguely that at the end of the 1811 German Coast Insurrection of the enslaved in Louisiana, the final revolutionaries had been hunted down in the swamps. For him, the restoration of benevolent slavery, as visible in Snowy Heron, was a happy ending. There was no illustration to The Runaway.

Racism and racialized seeing

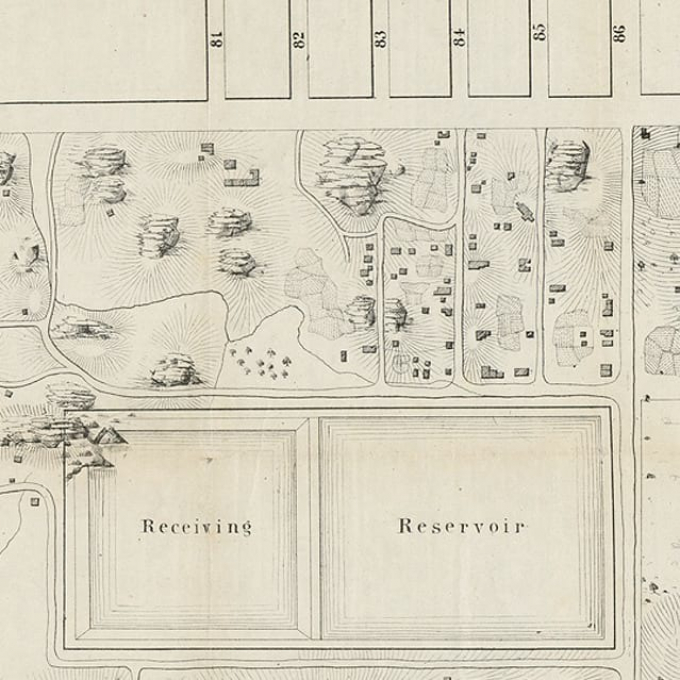

I don’t suppose Amy Cooper was thinking about Audubon. Any more than she considered that the Ramble–the “woodland retreat” where she let her dog run–was adjacent to Seneca Village, an African American community that was demolished to make the Park.

Seneca Village, though, faces the American Museum of Natural History, which all Park-adjacent New Yorkers have visited. This museum tells a story of racial hierarchy from the Roosevelt statue at the door to the racist “Pygmy” (Mbuti or Twi) diorama on the second floor. I bet you Amy Cooper went there.

As Fanon taught us long ago in reflecting on his own incident of being seen as a “Negro” on a French train around 1950, by the time the person is visually identified and named as a “type,” now updated to “African American,” nothing can stop what will happen. Amy Cooper probably believes she is not a racist. But her way of seeing is and when it took over because she panicked, so was she.