The NYC Monument Commission was a failure. It delivered a hot mess of recommendations for more: more bureaucracy, more signs and “>more monuments. This is called an “additive” policy. Without a commitment to anti-racism and decolonial practice, none of it makes sense. The missed opportunity is that a good faith anti-racist, decolonial project could show people of all backgrounds, including Italian-Americans, why the monuments must fall.

This is not trivial. While liberals want to make the racist president fall, they can’t even agree to take down statues of racist presidents. That’s why the monuments matter, as the white supremacists have long known. White racism remains “deniable,” even when said out loud, as the latest Trump scandal shows. It works as a particular structure of feeling, invisible to those on the “inside” (known as white) but all too real to those excluded. The monuments are palpable, immensely material nodes in the network of white supremacy.

What I’m arguing for is precisely an “art”–including museum practice, education at all levels, and activism–that takes decolonizing and anti-racism as its first principles.

In what follows, I examine

- how the report comes to decide to do nothing in the case of the President Roosevelt Memorial at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH)

- how the Memorial visibly incarnates concepts of racial hierarchy and was designed to be part of the Museum’s advocacy for eugenics

- how that agenda is an active part of the anti-immigration movement today

- how an anti-racist approach might offer a positive means to make the monuments fall.

- TL; DR? Skip to the action section at the end!

Before beginning, I want to note that the Commission was often divided and many members would probably agree with much of what I’m going to write. Somehow, the status quo always prevails, even when there is an exact divide as in the case of Roosevelt. Mayor de Blasio opted for no change in all cases, except for the statue of Marion J. Sims–a decision that now has to be reviewed by the community board and then the Public Design Commission, so don’t expect to see a removal any time soon.

1. Complexity

How did the decision to keep the Roosevelt Memorial, protested by the American Indian Movement as long ago as 1971, get taken? The key principle for the commission in relation to evaluating monuments is “complexity,” which receives an unlikely definition:

acknowledging layered and evolving narratives represented in New York City’s public spaces, with preference for additive, relational, and intersectional approaches over subtractive ones. Monuments and markers have multiple meanings that are difficult to unravel, and it is often impossible to agree on a single meaning.

This watered down version of the deconstructive principle of undecidability makes little sense. Complexity is the interpretation of how complexes work: a situation with multiple, intersecting elements but not a synonym for unintelligibility. Nor is it endlessly relative: in given situations, one vector is often determining. If monuments were really so unintelligible, it’s hard to imagine why so many of them have been built, let alone why people are so keen to defend them and why the Commission wants more to be built.

2. Making Race Visible

Here’s how this works in practice. While half the group clearly saw the Memorial as depicting racial hierarchy, “complexity” resulted because:

Some Commission members pointed to art-historical interpretations of the two standing figures as allegorical, representing the continents of the Americas and Africa, emphasized by the animals in relief on the parapet wall behind them. This analysis included evidence that the sculpture was meant to represent Roosevelt’s belief in the unity of the races. In this interpretation, the figures are in no way abject.

This statement is remarkably tendentious. Roosevelt’s 1905 speech on race made it clear that he believed in a limited equality of opportunity for both the “forward” (meaning white) and “backward” (meaning Black) “races.” But as the terms indicate, he did not for a minute think the “races” were equal. Historian Theodore Dyer noted in his 1980 book on Roosevelt and race that the president believed in “Anglo-Saxon racial superiority to American Indians and American blacks.”

Now, it is enough for someone to have an alternative point of view for there to be deadlock. Note that we are not discussing Fox News here but a sophisticated and widely-recognized group of art world luminaries and other professionals. But critiques of “race” or colonialism were not the priority of the majority who declared their

paramount values [to be] art, public space, and civic discourse

Paramount for whom? To what end?

Let’s look at the Memorial itself. In the two splendid photos by An Rong Xu above, it’s clear that the animals on the wall–we are, after all, at the Museum of Natural History–have no visible connection to the Memorial. The strikingly disproportionate scale of the figures discredits any idea that these figures are equal or unified. That’s even before the racialized stereotyping of the Indigenous and African figures are considered. And note the absurdly over-muscular and newly hirsute body of the Emperor-President as well. The contrast is unmistakeable and intentional.

The Commission’s claim that sculptor James Earle Fraser meant for the figures to represent the continents of Africa and America is advanced only in a Metropolitan Museum catalog entry to another sculpture without reference or documentary support. It is unconvincing. While there are well-known precedents for the Four Continents, like Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s 1872 group sculpture, The Four Parts of the World Holding the Celestial Sphere, I know of no precedent for a two continent sculpture before 1939.

On the other hand, New York City knew well Daniel Chester French’s famed sculptures of the four Continents on the Custom House downtown (1903-07). His America was a group in which an allegorical female figure actively dominates Indigenous figures: by that analogy, Roosevelt would be America and the two figures his dominated subjects. And that surely is the right way to see the sculpture. The group depicts Roosevelt dominating an African and American Indian as representatives, not of continents, but of “races.”

This analysis suggests why the Commission is so reluctant to act: if Roosevelt must fall, what is the case for French? Perhaps it’s a better sculpture in formal terms. But does it make sense that this vision of America trampling Quetzlcoatl underfoot is outside the New York Museum of the American Indian? And if so to whom?

3. Eugenics and Immigration

Why did the AMNH want a statue of Roosevelt at all? Because Roosevelt epitomized the eugenic, imperial racism the Museum wanted to promote. The Report suggests:

Approximately half of the Commission: believe that additional historical research is necessary before recommendations can be offered.

Direct information linking Roosevelt, the AMNH, the Memorial and eugenics is, in fact, widely available: here is a summary.

The AMNH was a bastion of eugenics under the long directorship (1908-33) of Henry Fairfield Osborn. In 1916, Osborn wrote the preface to Madison Grant’s The Passing of the Great Race (later much admired by Hitler):

Race implies heredity, and heredity implies all the moral, social, and intellectual characteristics and traits which are the springs of politics and government. Conservation of that race, which has given us the true spirit of Americanism, is not a matter either of racial pride or of racial prejudice; it is a matter of love of country

Environmental conservation was not, then, the “good” side of the AMNH in contrast to its “bad” racism: they were part and parcel of the same race politics. Roosevelt supported eugenic principles, saying in 1914

I wish very much that the wrong people could be prevented entirely from breeding; and when the evil nature of these people is sufficiently flagrant, this should be done.

Osborn unsurprisingly campaigned for a Roosevelt Memorial at the AMNH as soon as the president died in 1919. He gained his greatest success in helping pass the Immigration Act of 1924 that severely limited immigration, especially from Eastern and Southern Europe. This Act inspires the current administration’s opposition to immigration, leading to Osborn’s race theory being quoted on the front page of the New York Times this weekend. In other words: this is not over.

In the context of rising fascism and support for race science and eugenics, the Third International Eugenics conference was held at the AMNH in 1932. Osborn’s keynote was a jeremiad against birth control and for what he called “birth selection.” He repeated that environmental conservation was a key part of “improving the race,” meaning white people. His address noted six “overs” in the then-present:

Over-destruction of natural resources….Over-population…with consequent permanent unemployment of the least fitted. I have reached the conclusion that overpopulation and underemployment may be regarded as twin sisters

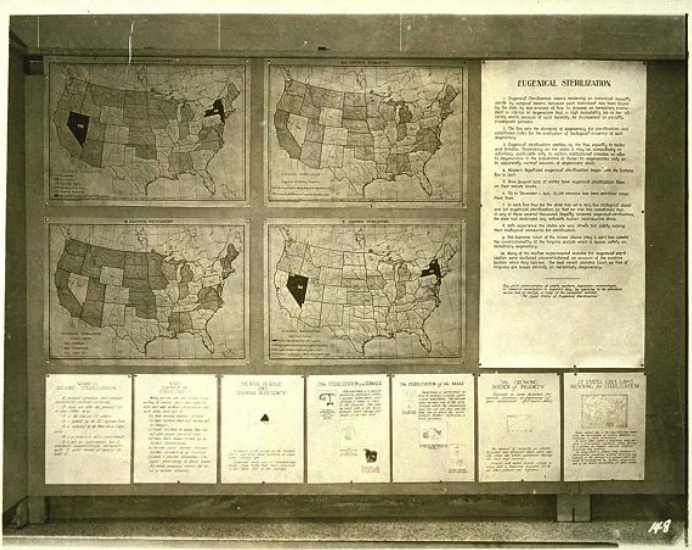

In short, his proposed solution for the mass unemployment caused by the Depression was eugenic birth selection, including forced sterilization, as the exhibit made clear (see image above), noting that over 15,000 enforced eugenic sterilizations had been performed by 1932 in the United States, including a small number in New York State. Upheld by the Supreme Court in 1927 in an opinion written by Oliver Wendell Holmes, there would ultimately be over 70,000 such sterilizations in the US.

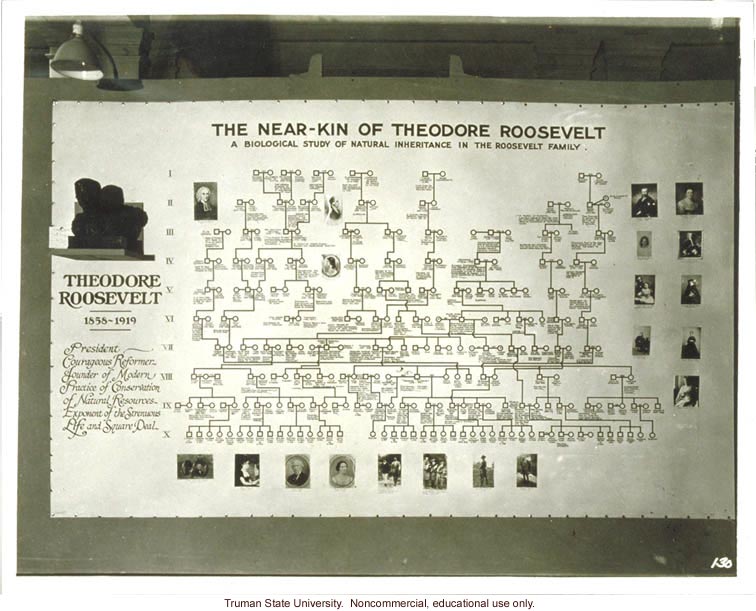

Good examples of birth selection were on display at the Eugenics Conference as well, such as the all-white membership of Congress. Notably, there was a display of the eugenically desirable “pedigree” of Theodore Roosevelt.

In case there is any doubt as to the connection of the Memorial under construction at the AMNH to this chart at the time of its display, a sculpted bust of Roosevelt is placed at the top left.

And the AMNH Trustees said as much when the Memorial was opened in 1936, just after Osborn had died:

For more than sixteen years the late Professor Henry Fairfield Osborn had given his time, energy and thought to produce a structure, which he felt would best memorialize Theodore Roosevelt. …The trustees of the American Museum of Natural History, who will later control the operation and maintenance of the memorial, have pledged themselves, …, to carry out the educational purposes laid down by their late President Osborn for their guidance.

Central to Osborn’s life work was the racist hierarchy of eugenics, the control of immigration, the deportation of unwelcome migrants, and the enforced control of human reproduction. It is impossible that the Trustees meant anything else.

4. Eugenics Now

Nor are these eugenics solely a thing of the past. This week it emerged that University College London has been holding a series of eugenics conferences, calling for the “phasing out” of “populations of incompetent cultures.” These events are funded by an unpleasant US-based outfit called The Pioneer Fund. This group was founded by Wycliffe Draper, a collaborator of Osborne’s. His nephew Fairfield Osborn was a founding director and continued to work with Draper until they split in the late 1950s.

Today, the Fund supports white supremacist Richard Spencer, who was active at Charlottesville, and it continues to promote old-fashioned Jew hatred.

But it’s not just the lunatic fringe. The continuance of eugenic ideas occurs every time someone calls someone else a “moron” or an “imbecile,” which were categories of eugenic deficiency. Or when Donald Trump says “laziness is a trait in blacks.”

Trump is adept at the art of racialized provocation. The day after his “shithole” remarks, he appeared to the press in front of a portrait of Teddy Roosevelt.

There is no danger that Roosevelt will be forgotten or erased from history if his statue is removed. The point is rather that his statue is part of an active network of racialized signification. Which is to say: how does race have meaning? It connects. It links Trump to Roosevelt via the idea of the dominant Hero, whiteness, and white supremacy.

5. Why Everyone Should Want the Monuments to Fall

In the Commission Report on the Columbus Monument, the 1891 lynching of eleven Italian Americans in New Orleans is cited to explain why the Monument was needed. Indeed, this period saw the notorious “one drop” rule in Louisiana, meaning that a person with any non-“white” descent at all was considered “colored,” to use the terminology of the time. In 1892, Homer Plessy boarded a segregated railway train in New Orleans, leading to the Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson that upheld “separate but equal.”

It was in this intensely racialized context that the Columbus Monument was erected in New York. The claim Italian-Americans were making was to be “white.” And it’s not hard to understand why, given the then-ongoing violence of white supremacy. But that is no reason to sustain the argument today. Without even considering Columbus’ devastating impact for Indigenous peoples–though of course in a wider frame we should– present-day Italian-Americans and other “whites” should not want to be white in the manner of 1892. And that’s what this Monument means. But it didn’t work.

The 1924 Immigration Act set the annual quota of any nationality at 2% of the number of foreign-born persons of such nationality resident in the United States in 1890. According to eugenic theory, there is not a single “white” European “race” but rather three. The eugenically preferred “Nordic” race is truly “white.” Distinct were Southern Europeans–mostly Italians for practical purposes–and Eastern Europeans, meaning Jews. The 1924 Act intended to promote Nordic immigration and limit that of Southern and Eastern Europeans.

The results of the Act were dramatic. From 1901-1914, 2.9 million Italians immigrated, an average of 210,000 per year. Under the 1924 Act, only 4,000 per year were admitted–a 98% decrease. These restrictions did not end until 1965 and Attorney General Sessions has cited the 1924 Act as an inspiration for current attempts to limit immigration.

In short, while Italians in 1892 certainly had a case that they had been violently subjected to white supremacy, their perhaps understandable attempt to join its ranks by means of the Columbus Monument did not succeed. Today, no one questions the “whiteness” of Italians and all Europeans are considered “white.” But this is not a club that anyone should want to belong to.

Just as several Italian-Americans advocated at the NYC Commission hearings, anti-racist Italians should support removal of the Columbus Monument. An anti-racist campaign would connect Italian-Americans to a different history, the long arc of justice. But prominent New York leaders like Andrew Cuomo and Bill de Blasio have made it clear they want no part of this anti-racist rethinking of whiteness. The majority of the Commission followed this lead.

6. Action

- All the monuments are connected. The Columbus Monument made the claim that Italians were white in the moment of legalized segregation. Roosevelt’s support for eugenics was why Osborn and the American Museum of Natural History wanted a memorial. The same people supported the 1924 Immigration Act that cut Italian immigration by 98%. In short, the “whiteness” these monuments embody excludes almost everyone and perpetuates systemic and hierarchical racism.

- The monuments must fall not because people were bad then and we are good today but because the racism they embody is still active and growing.

- Building more monuments or putting up signs is not a substitute for the long and difficult work of anti-racism. Anyone can say “I am not a racist.” The question is “what are you doing to end racism?

- The Commission thinks that action should be taken in regard to monuments if there is: “Sustained adverse public reaction (two years of more); and/or Instantaneous large-scale community opposition.” So let’s give it to them.