On June 30, 2015 the Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, VA, was tagged “Black Lives Matter.”

In the ensuing protests against Confederate memorials and other racist statues, only 60 or so came down. Five years later, the protestors in the streets after the murder of George Floyd remember. And from Birmingham, AL, where a Confederate statue came down to Philadelphia where the statue of a racist cop was removed, the monuments are falling. Because these are not “just” statues, they are part of the apparatus of white supremacy. Once more, white people, this is on us: take down the monuments!

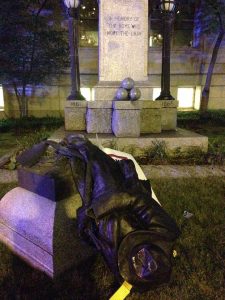

WATCH: VIDEO of Former Philadelphia Mayor Frank Rizzo bronze sculpture lifted off then driven away in truck overnight. It looks as if he’s waving goodbye @FOX29philly pic.twitter.com/hTxH7dqato— Steve Keeley (@KeeleyFox29) June 3, 2020

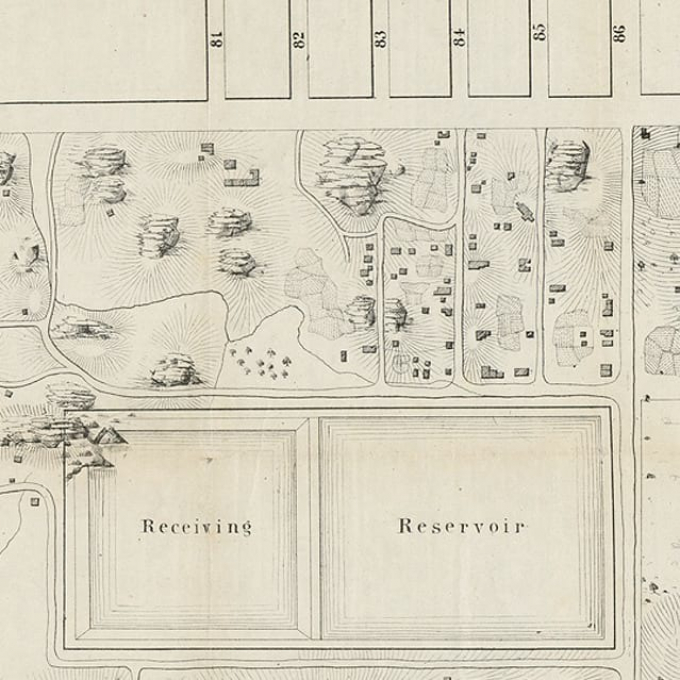

Recall how long this war has been going on. What was called the “war on statues” began in decolonized Algeria in 1962. It spread across Africa and culminated with the removal of the statue of Cecil John Rhodes from the University of Cape Town in April 2015. The decolonizing project crossed over the Atlantic and instigated the statue removal movement in Charlottesville and then across the United States. Last November, statues of conquistadors were dethroned in Chile.

Old Targets, New Tactics

In this rapidly-changing moment, old and new tactics and goals are emerging for the monuments movement. In Richmond, Virginia, protestors tagged statues like that of J.E.B. Stuart (below, a Confederate hero who served under Lee), which was also the model for Kehinde Wiley’s nearby sculpture Rumors of War, notably left untouched by protestors.

In a targeted act of erasure, the headquarters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the organization that funded so many of the Confederate memorials, was set on fire. Are you outraged? As long ago as 1963, James Baldwin warned America: “the fire next time.” If the statues had been removed, maybe there would not have been these fires.

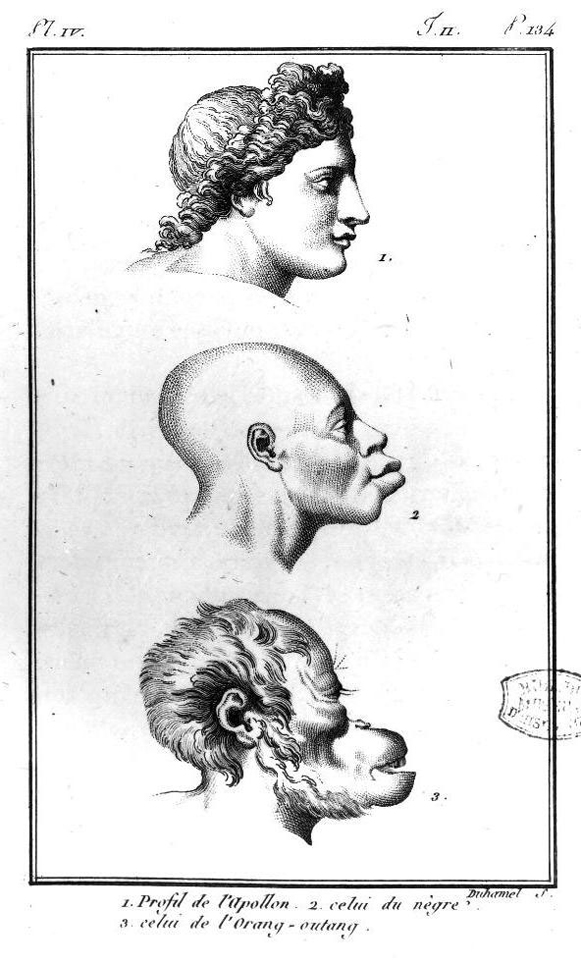

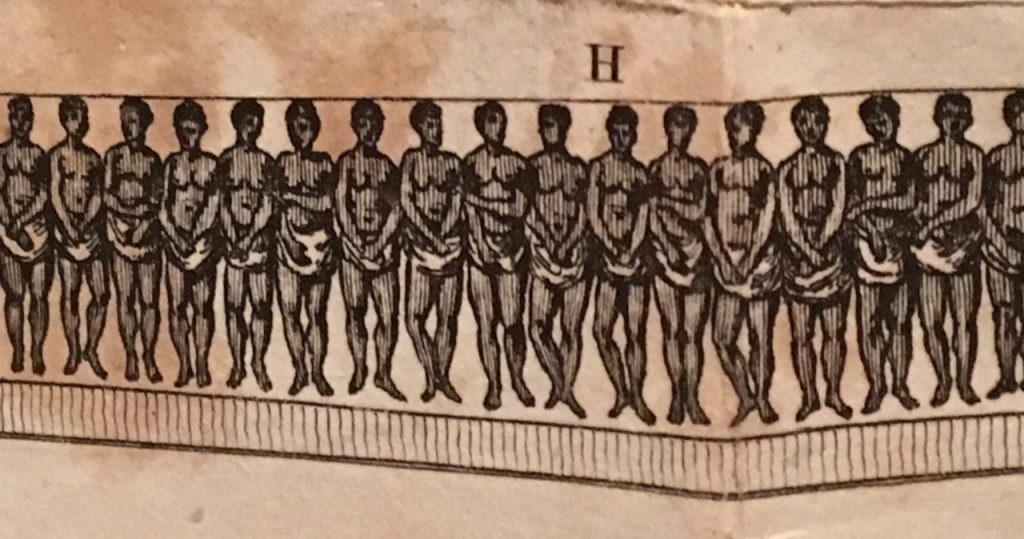

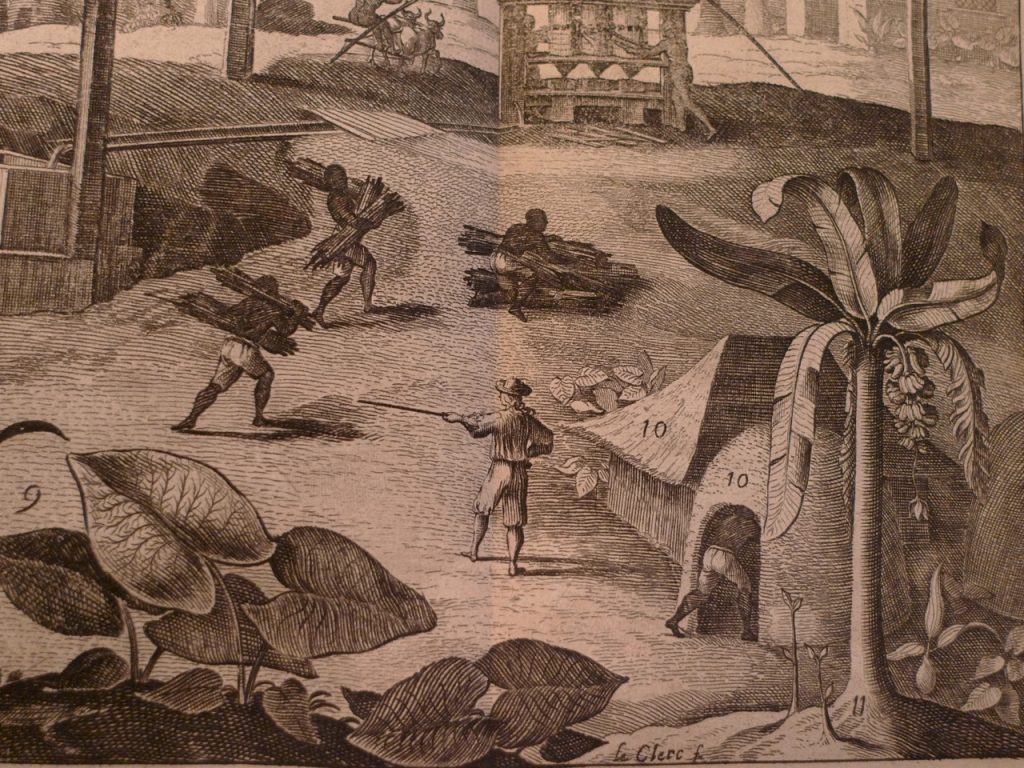

In Louisville, a protestor removed the right hand of Louis XVI (above). The tag on the statue reads: “All Cops Uphold White Supremacy.” The action and the tag condense a historical understanding of sovereignty in plantation culture into a single image. Let’s unpack this work. The king’s surrogate in the plantation was the overseer, whose hand could be raised to punish or kill. By condensation, sovereignty became white supremacy.

Like the king, the overseer had two bodies: his own, and a second one that never died and never slept. This second body became the emblem of white supremacy. It was, in effect, a statue that sustained the racialized surveillance of the plantation.

In Louisville, Louis XVI as the emblem of white supremacy continues to survey what Black geographer Kathleen McKittrick calls the “plantation future,” which is to say:

“a conceptualization of time-space that tracks the plantation toward the prison and the impoverished and destroyed city sectors”

Kathleen McKittrick “Plantation Futures,” Small Axe (2013): 2

It is entirely consistent that a protest against police brutality would target the statue of the colonizer king. The tag on Louis’s base understands that the cop and the prison guard are the plantation futures of the sovereign-overseer. Removing the hand of the king is an act of what Christina Sharpe calls “redaction,” a gesture that erases in order to make it fully clear what there is to see.

The Cop-Overseer

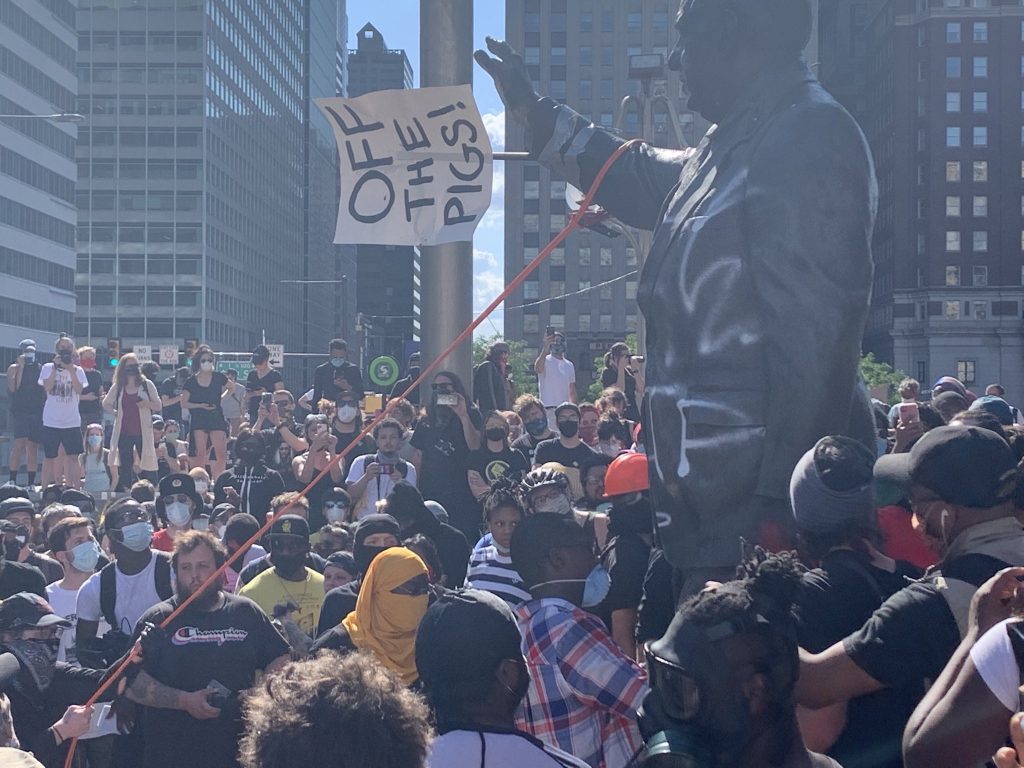

It was, then, no coincidence that on the same day, protestors in Philadelphia were attempting to overthrow the oversized statue of notorious police officer Frank Rizzo. Given Rizzo’s long history of racist statements and actions, Black Lives Matter had targeted the statue in 2016 and most residents agreed it should be moved. But it wasn’t. The statue resisted efforts to topple it and city authorities rushed to clean it the next day.

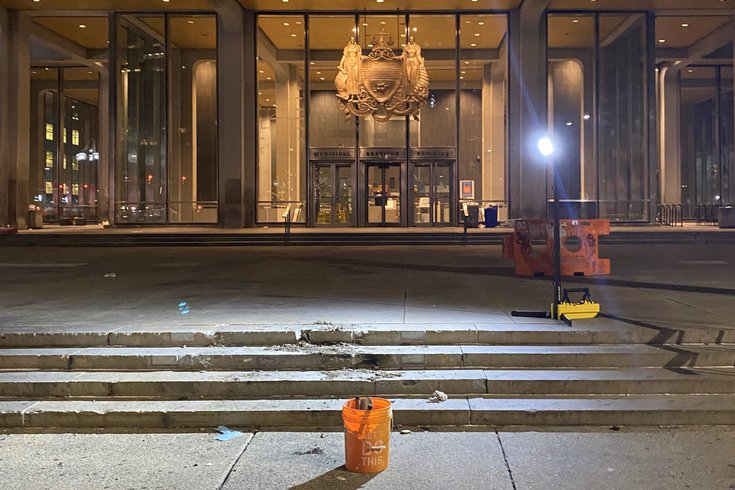

Having said that removing the statue was not even in his top 100 priorities, Philadelphia mayor Jim Kenney reversed course overnight on June 2 and had the Rizzo statue removed. Now it’s clear to Kenney that the statue represented “bigotry, hatred and oppression.” And that this is just a beginning. Finally, a North-Eastern city takes a lead on this issue.

The statue issue has long revealed the hypocrisy of white liberalism, condemning the South while leaving its own hateful monuments in place because they are not actually Confederate monuments. Bill de Blasio in New York failed to take down the Roosevelt Statue and the Columbus Monument, or even to remove a marker placed on Sixth Avenue to commemorate a parade for the fascist Marshal Pétain of Vichy that was only installed in 2003. So now the focus is again on New York. Can the city step up?

Memory matters

The removal of the Rizzo statue shows that who and what is, and is not, remembered does matter, as an extension of the thought experiment “Black Lives Matter.” In a lyric essay published via social media, Oglala Sioux poet Layli Long Soldier was prompted by George Floyd’s murder into a reflection into the “old, yet very present energy” of historical accounts.

White liberals have mostly argued that monuments are history and removing them would erase that history. This view consigns history entirely to the past. The monument as past artifact becomes history just by virtue of not being from now.

But for McKittrick and Long Soldier, they are absolutely “now.” And they defend and project a certain vision of the future as settler colonial white supremacy. For Long Soldier, history does not take stone form:

“we remember who we are from our families, from this land, from stories within the community, and from our senses. Yes, from our senses, we remember what’s stored within us already.”

Layli Long Soldier, “On The Murder of George Floyd: For George Floyd, his family, and for all who are deeply affected” (June 1, 2020)

Her “we” is that of the Indigenous community, not mine. But as she often does, Long Soldier does “ask you, warmly, to return to accounts from our Lakota ancestors.” I take that “you” to be the non-Native reader, who needs to reconfigure their understanding of how past experience can be passed on.

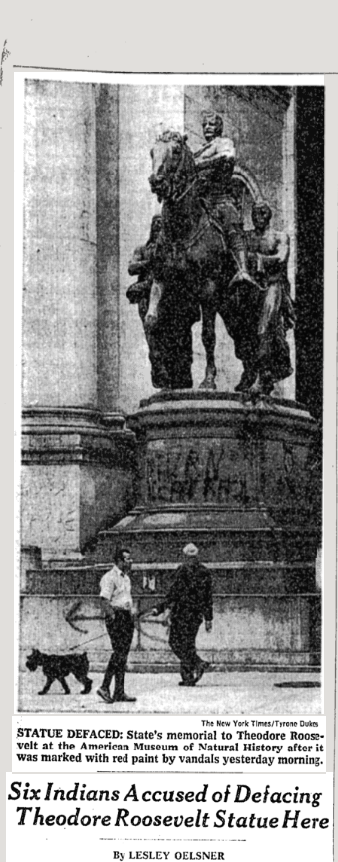

She turns to a reflection on the history of the American Indian Movement, founded in Minneapolis. An early AIM-related action was the spilling of blood-like paint over the doubly-racist statue of Theodore Roosevelt outside the American Museum of Natural History in June 1971.

The tags read “Return Alcatraz,” referring to the Indigenous occupation of Alcatraz Island. And “Fascist Killer,” meaning Roosevelt. Six young Indigenous people affiliated with the National Indian Youth Council carried out the action. They’ll be in their 70s now.

The American Museum of Natural History has found time to furlough more than 450 employees already. Let’s make it one more and finish the antifascist action from 1971. Bill de Blasio, reverse the weak decision from 2017 and take this monument down. Along with all the others.