Category: Hunger strike

-

Don’t Look Back in Anger #Day40

Forty symbolizes the overcoming of hardship. The Israelites wandered for forty years, while Jesus spent forty days in the desert. For hunger strikers, forty days marks the passage into system failure–the hearing goes, sight fails, the body collapses. Despite everything, let’s hear the call from Manchester: “don’t look back in anger.” The failure of the…

-

Manchester-Palestine: A Dialectical Image

For Manchester and Palestine, in solidarity In the flash of the media cameras and the detonation of a bomb, Manchester and Palestine yesterday became a dialectical image of the present. The invisible, drawn-out suffering of the hunger strikers in Palestine shatters against the hypervisible instant of mass mediated murder. The clash of two sets of images…

-

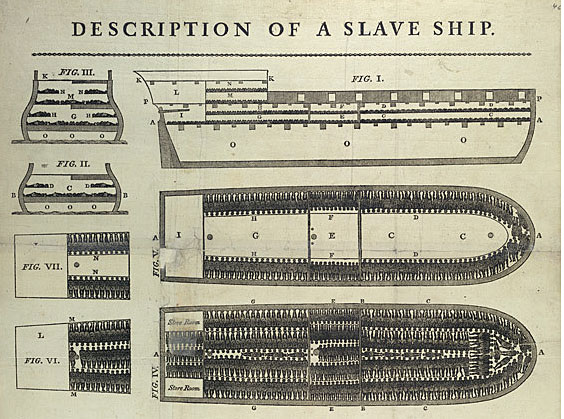

The Long Hunger Strike (Against Slavery)

These posts are difficult to write and I’m sure they are difficult to read. By measuring the time taken to write–or to read–it is possible enter the symbolic world created by the hunger strike, a world in which existence matters. It is the force of the statement made by the strike that enables this fragmentary…