Tag: Black Lives Matter; monuments

-

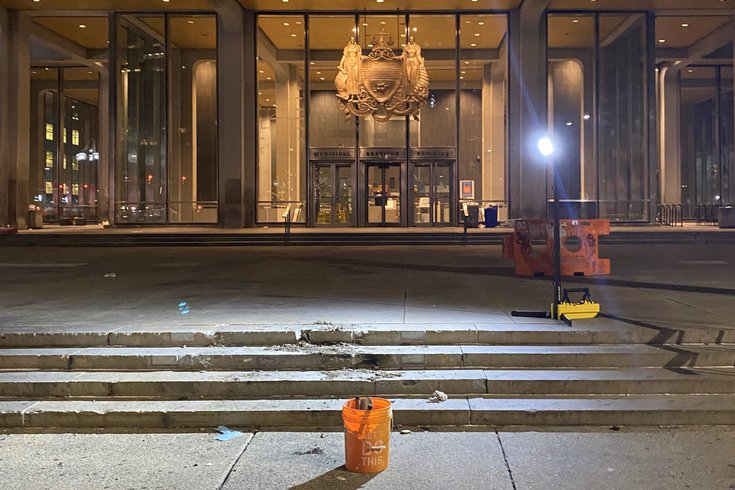

Once More, The Monuments Must Fall

“Black Lives Matter” protestors in the streets after the murder of George Floyd continue to demand that all the monuments must fall because they are part of the apparatus of white supremacy. In Birmingham and Philadelphia they are down. Once more, white art people, this is on us: take down the monuments!